Taiwan Strait Supply Chain Risk: How East Asia Keeps Learning if Trade Stops

Input

Modified

A Taiwan Strait shock would choke energy, chips, and shipping that keep East Asia learning Japan/Korea: oil-route risks; ASEAN: migrant, logistics, student shocks Protect schools now—fuel, offline kits, spares, regional compact

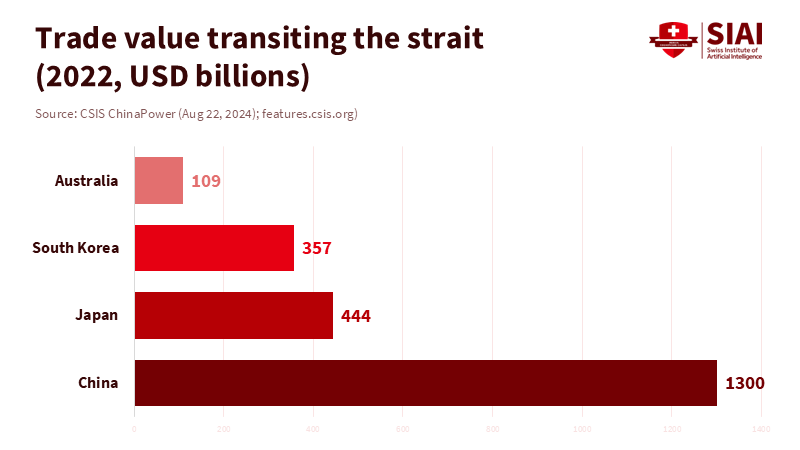

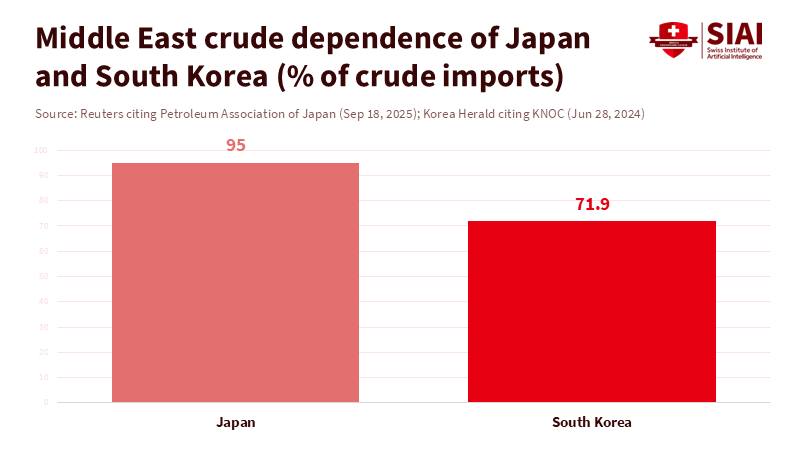

The core of East Asia’s economy fits into a strait barely 180 kilometers wide. In a typical week in 2023, around 1,200 ships crossed the Taiwan Strait, making it one of the busiest maritime routes in the world. China channels approximately $1.3 to $1.4 trillion of its trade through these waters. Almost a third of Japan’s imports, and nearly a third of South Korea’s, also pass through the strait. Most of Japan’s crude oil and two-thirds of Korea’s come from the Middle East along routes that pass Taiwan. This is not just a theoretical shipping map; it affects school calendars, exam schedules, laptop deliveries, bus fuel, lab reagents, and hospital training rotations. If the strait closes due to a blockade, quarantine, or prolonged crisis, the urgent question is no longer about deterrence. The question becomes how to maintain education across ASEAN, Japan, and South Korea under severe conditions. This is the real Taiwan Strait supply chain risk for education systems.

The map: Taiwan Strait supply chain risk ties ASEAN, Japan, and Korea together

Let’s start with exposure. CSIS estimates that 32% of Japan’s imports and 25% of its exports—about $444 billion—passed through the Taiwan Strait in 2022. For South Korea, it is 30% of imports and 23% of exports, or about $357 billion. China is even more dependent: about $1.3 trillion in imports and exports used the strait in 2022. Oil and gas increase the risk: over 95% of Japan’s crude and about 65% of Korea’s crude come from a few Middle Eastern suppliers, with tankers usually taking the shortest route through the strait. Rerouting through the Luzon or Miyako straits adds distance, delays, and insurance costs. CSIS models that one standard alternative route adds roughly 1,000 miles. Schools and universities experience this through higher electricity prices, late devices, and canceled field courses well before any formal conflict.

The geography does not isolate ASEAN from this risk; it connects ASEAN to it. The Philippines sends about one-fifth of its imports and one-seventh of its exports through the strait, even though some shipments can divert east into the open Pacific. Mainland Southeast Asia can transport more over land, but still relies on maritime inputs that cross or edge the strait. More troubling is the human link: over 700,000 Southeast Asians work in Taiwan, many in care and industrial jobs. A crisis leaves a workforce the size of a small city stranded, complicating evacuation and cutting remittances. Those are education shocks too—parents, teachers, and students lose income; care gaps emerge in schools in Taiwan and back home.

Technology sharpens the stakes for education. Taiwan produces around 60% of the world’s semiconductors and over 90% of the most advanced chips by node, while South Korean companies dominate memory production. A blockade could reduce global output by 2.8% in the first year, a financial blow far exceeding most education budgets. In classrooms and labs, this results in shortages of Chromebooks, servers, sensors, and replacement parts. It also creates an equity problem: the poorest schools and regions wait longest and pay the most. The supply chain supports every login screen.

Japan and South Korea: shared threat, different strategies

Tokyo sees the Taiwan Strait as a direct risk to national security and economic stability. Japan’s National Security Strategy and defense white papers highlight that peace and stability across the strait are crucial for Japan. In August 2022, Chinese ballistic missiles landed in Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone, firmly establishing the geographic risk in the public mindset. Since then, Japan has accelerated the fortification of the Nansei island chain, planned new missile units near Taiwan, and strengthened logistics with allies—all while emphasizing the energy lifeline that runs past Taiwan and the necessity of keeping sea lanes open. Japan’s education authorities and universities should interpret these decisions as a signal: maintaining learning will depend on energy security and maritime resilience.

Seoul’s approach is more cautious but evolving. For decades, South Korea has handled its Taiwan strategy with strategic ambiguity, concerned that a crisis in the strait could divert U.S. resources from the peninsula and encourage Pyongyang. That view is changing. The current South Korean dialogue links Taiwan’s security to Korea’s economic security and sea lines of communication. Analysts suggest realistic roles for Korea that won't weaken deterrence on the peninsula: protecting regional sea routes, enabling allied mobility, and maintaining strategic balance while ensuring readiness at home. The difference from Japan remains—Seoul has a higher threshold for direct involvement—but there is growing alignment on what counts for educational resilience: protecting shipping and energy flows that keep schools powered and devices working.

The practical implication is clear: different defense attitudes need not hinder joint civilian planning. Japan’s clearer stance and Korea’s caution can still support the same educational continuity framework—shared logistics corridors, prioritized fuel allocations for hospitals and schools, effective emergency communications, and predefined maritime strategies to keep essential goods moving. A crisis will reward this quiet cooperation more than gestures of solidarity.

ASEAN’s education and humanitarian stakes

The educational perspective clarifies ASEAN’s priorities. Hundreds of thousands of Southeast Asian migrant workers in Taiwan support eldercare, fisheries, and factories—jobs that directly impact household incomes and community stability back home. ASEAN governments face a difficult challenge: adhere to One-China policies, avoid political statements, but still coordinate assistance and evacuation plans for their citizens. The right approach is pragmatic, not performative—shared contact points in Taipei, combined transport and staging, reciprocal consular support, and data-sharing on who needs help first. This is also an education issue: remittances fund tuition; caregivers allow teachers and parents to work; disruptions affect school attendance and instructional time. Planning humanitarian routes means keeping kids in school.

Student mobility makes the case even stronger. Japan hosted about 337,000 international students as of May 2024, mainly from Asia; South Korea surpassed 250,000 by 2025 and aims to grow further. These flows are not gifts; they are vital regional pipelines of human capital. If the Strait disrupts air and sea schedules, exchange programs falter, short-course certifications lapse, and lab-based degrees miss important milestones. Shipping is the hidden limitation: when 1,200 vessels cross the strait weekly, even minor diversions affect exams and equipment deliveries. Ministries should view these numbers like fuel inventories: if they drop, learning halts.

Lastly, there are many subtle dependencies. Science classes require sensor kits; vocational schools need machine parts; telehealth training requires secure networks. If shipping routes move east of Taiwan or take the Miyako Strait, delivery times lengthen, and spare parts become scarce. If advanced chips become limited, education technology vendors will ration devices and support. The first affected are often rural schools and small private colleges. The quickest solution is not dramatic; it is procurement diversification, pooled purchasing, and pre-ordered inventories that account for weeks, not days, of delays.

What must schools, universities, and ministries do now?

Start with energy and connectivity. Prioritize schools and hospitals in national emergency fuel plans; this should be enforceable across agencies. Pre-contract diesel and LNG where necessary; equip campuses with demand-response controls and micro-grid-ready systems; store crucial power electronics that may fail during voltage spikes. Save “offline-first” curriculum bundles on school servers and district data centers; back up exam banks and learning management systems domestically. The aim is simple: a school should be able to teach for weeks, even with an unstable grid and unreliable internet. These steps are cheaper than canceling a term and can fit within current budgets for maintenance and technology upgrades.

Develop a regional “Learning Continuity Compact” that brings together ASEAN, Japan, and Korea. The compact is not for show; it consists of mutual hosting and credit-transfer protocols triggered by disruptions. Agree that students displaced from any affected campus can finish the term at a partner institution with recognized modules. Issue emergency visas and extend health insurance for 90 days. Build regional device pools for quick shipment to low-income areas. Set up a small joint logistics team to collaborate with port authorities and prioritize educational and hospital cargo during reroutes. The compact should also establish a communication channel with shipping insurers, ensuring that priority cargo receives reliable coverage even when rates rise.

Address the semiconductor issue as if it were a textbook adoption cycle, not a game of chance. Map the silicon in your school systems now: device models, chipsets, spare ratios, warranty status, repair networks. Extend device lifetimes with mid-cycle RAM or SSD upgrades, and adopt reasonable specifications for standardized assessments and introductory coursework. Partner with various vendors in Japan and Korea for memory and storage needs. Support pilot programs that use open hardware where possible. For universities, shift less urgent computing needs to allied cloud regions and budget for higher unit costs. Policymakers should co-fund repair hubs and parts depots in Japan, Korea, and ASEAN, as repair is the easiest way to convert chip scarcity into learning time.

Plans for human capital should prepare for both evacuation and an influx of workers. Identify the skills of returning migrant workers and their spouses—many are caregivers, machinists, or line supervisors—and offer short bridging certificates to integrate them into local healthcare systems or vocational education programs. Train a reserve of bus mechanics, lab technicians, and IT support staff who can step in at schools if supply chain disruptions hinder the availability of typical contractors. Provide financial support to keep students enrolled when remittances decline. None of this is glamorous. All of it ensures continuity in the only metric that matters in a crisis: the number of hours of safe, productive learning delivered.

The numbers that started this discussion are not abstract: 1,200 ships weekly, $1.3 to $1.4 trillion of Chinese trade, a third of Japan’s imports and a third of Korea’s, most of their oil—all threading a narrow corridor by Taiwan. The easy reaction is to push for deterrence and leave it to defense planners. The responsible response is to strengthen education now: prioritize energy, secure connectivity, ensure inventories are ready, prepare student pathways, and create a regional compact that treats schools and hospitals as essential cargo. If we build that structure, the worst-case scenario becomes a tough semester instead of a lost year. If we ignore it, the first casualty of a maritime crisis will be classroom time. East Asia’s economies can recover from delays, but children do not get their time back. Keep the learning going, no matter what.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brookings Institution. (2024, Feb. 22). How Japan and South Korea diverge on Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait.

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). (2024, Aug. 22). How much trade transits the Taiwan Strait? ChinaPower Series.

East Asia Forum. (2025, Dec. 4). ASEAN must be ready if Taiwan crisis hits.

European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR). (2025, Nov. 25). The Taiwan test: Why Europe should help deter China. (Semiconductor shares cited).

International Institute for Economics & Peace / Vision of Humanity. (2025, Jun. 16). The world’s dependency on Taiwan’s semiconductor industry is increasing. (Global output impact cited).

Office for National Statistics (UK). (2024, Apr. 24). Ship crossings through global maritime passages: Jan 2022–Apr 2024. (Weekly transits cited).

Comment