Learning by Walking the Line: How US–Japan Knowledge Transfer Built an Aerospace Playbook and What to Protect Next

Input

Modified

Factory tours scaled US–Japan know-how Aerospace: from licenses to composite wings Open collaboration with firm research security

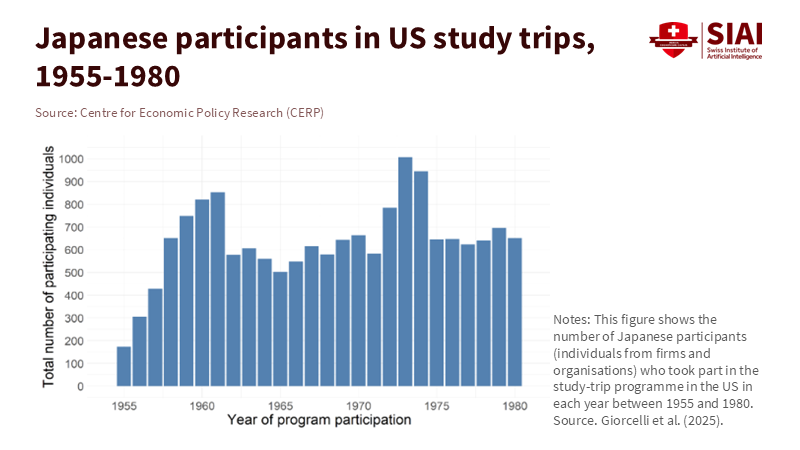

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, 400 to 500 Japanese firms sent managers on organized study tours to U.S. production sites each year. The groups stayed for weeks. They observed line changes. They attended classes to learn the Training Within Industry program. And they returned home with binders of shop-floor routines. This scale is significant. It transformed US–Japan knowledge transfer from a few visits into an education system that reached across the nation. Although U.S. funding ceased in 1961, the tours continued under Japan’s initiative, with 80-90% of the destinations still American plants. The result was not magic; it was method—a structured pipeline for managerial know-how. This pipeline continues to influence strategic industries today, from carbon-fiber wings to advanced engines. To promote resilient innovation now, we must treat this pipeline as a system to manage, not a stroke of luck. We should also combine openness with research security to ensure that what we share makes us safer, not more vulnerable.

Reframing US–Japan knowledge transfer as an education system

The tours were not random. They were carefully planned, timed, and focused. Managers were grouped by sector or topic, trained on Job-Instructions, Job-Relations, and Job-Methods, and shown concrete routines they could implement back home. Many of the participating firms were large, publicly listed manufacturers, which allowed the practices to spread through dense supplier networks. The scale is evident in the numbers: thousands of individual participants, hundreds of firms each year, a clear early focus on the U.S., and more attention to Europe after 1961. Evidence shows the greatest post-tour gains appeared in employment and sales over one to two decades, even if measured labor productivity did not increase as significantly. Learning was cumulative and organizational, not a quick fix. This is what an education system looks like when it operates within the production system.

This perspective helps us avoid a stale debate about “copying” versus “originality.” The essence of US–Japan knowledge transfer was disciplined observation combined with re-contextualization. Japan’s postwar managers adapted routines to a tight labor market and supplier keiretsu, building long-term capacity rather than short-term achievements. The U.S. benefited as well: American firms and labs learned from Japanese lean methods during the 1980s and 1990s, and cross-investment raised joint quality standards. Today, the collaboration is broader and more focused on science. Japan spends about 3.3-3.4% of GDP on R&D, one of the highest rates in the OECD. The United States contributes roughly 30% of global R&D spending and nearly a quarter of a million internationally coauthored articles each year. The two countries also rank among the top partners in high-quality publications according to Nature Index metrics. This is still an education system, now encompassing labs, code, and space as much as shop floors.

Inside the aircraft case: from licensed fighters to composite wings

Aerospace illustrates how US–Japan knowledge transfer evolved from imitation to co-creation. In the 1950s to 1970s, Japan licensed the production of U.S. aircraft—such as F-86 fighters at Mitsubishi, F-104s at Mitsubishi/Kawasaki, and later F-4 variants—through structured coproduction and offsets. The goal was clear: rebuild design, tooling, and quality culture while fulfilling alliance needs. U.S. audits and training established standards; Japanese firms adopted these standards and developed supplier depth. A 1982 U.S. government review found these programs directly helped Japan’s civil aircraft industry by improving technical competence and shop-floor discipline. Early transfers were not a detour; they laid the foundation for indigenous design and the supplier capabilities that would later support Boeing, Pratt & Whitney, and GE.

Fast forward: Japan now builds the composite wing box for the Boeing 787, with Japanese suppliers contributing about 35% of the aircraft’s value—the highest share Japan has on any Boeing program. For the upcoming 777X, the Japanese contribution is lower, around 21%. Still, the capability base is both deeper and more automated, reflecting a shift from licensed knowledge to global leadership in carbon-fiber structures. These contracts are not isolated deals; they represent trust, quality, and scheduling discipline. They rely on decades of joint training and continuous improvement, and they still depend on shared standards for nondestructive testing, cybersecurity, and export compliance.

Aerospace engines reflect a similar story. U.S.–Japan connections in aero-engines involve licensed maintenance, component co-design, and long-term risk-sharing. The National Academies described these connections as "extensive and longstanding," covering a range of mechanisms from joint ventures to shared test protocols. The path is not always straightforward. However, the pattern remains: initial transfer reduces uncertainty; supplier specialization follows; and, over time, learning curves converge on coordinated upgrades. This is how strategic interdependence can be a competitive advantage instead of a weakness—by making the learning itself the product.

Research security: guardrails for open collaboration

Today's frontier extends beyond factory floors. It includes code repositories, satellite data, and lab notebooks. Openness fuels discovery, but it also brings risks. U.S. policy now defines research security as the protection of the system from theft, interference, and related integrity issues. This definition serves as a valuable baseline for US–Japan knowledge transfer in sensitive areas like semiconductors, quantum, and space. In 2024 and 2025, leaders in Washington and Tokyo plan to take new steps to align acquisition, science, and technology ecosystems; enhance joint air and space projects; and connect economic security to trustworthy R&D practices. These actions are not superficial; they indicate that trust now requires screening of shared data flows, improved disclosure practices, and coordinated responses when guidelines are violated.

Critics are concerned that stricter regulations will hinder scientific progress. However, publication data suggest a different trend. International collaboration has risen sharply in both nations, and the US–Japan partnership remains one of the most successful in high-impact journals. The challenge is to strengthen foundational practices—with clear expectations for affiliations, funding disclosures, lab access, and dual-use risks—without limiting opportunities. A practical approach combines proportional vetting for sensitive projects with simpler pathways for others. CSIS analysts describe this shift in collaboration as "from ground to cloud": make the everyday rules work for bench scientists, then expand them across digital platforms and shared computing. This entails standardizing training modules on data management, credentialing visiting researchers, and co-developing incident response plans to prevent issues from escalating into policy crises.

Beyond bilateral: a new playbook for trusted knowledge transfer

The original tours were effective because they created learning structures rather than just field trips. We can construct similar modern versions. First, establish joint “methods semesters” where mid-career engineers rotate through partner firms to learn standard operating procedures for AI-assisted design, model validation, and cyber-physical testing. Second, organize co-investment to reward teams that publish shared benchmarks, not just academic papers. Third, implement a standard toolbox for export-controlled research that uses the same forms, checklists, and audit trails on both sides. These steps may sound bureaucratic, but they are essential for rebuilding the practice of US–Japan knowledge transfer in an era where the classroom is a cleanroom, and the lesson plan is a secure repository. Joint leaders’ statements in 2024 and 2025 already point in this direction, covering areas from lunar exploration to missile-tracking satellites and AI model collaboration. Policy should now support these initiatives with funding for repeatable cohorts.

Educators play a vital role. Universities can anchor this system by designing for transfer: capstone projects managed by binational teams; shared IP templates that can be negotiated quickly; cross-listed courses on safety and integrity that are concise, specific, and required. Administrators should treat visiting cohorts as the tours once did—prepare for months, conduct tight two- to six-week sessions, and follow up for a year. Policymakers should subsidize rotations like they previously funded travel and housing, measuring success by adoption, not public announcements. Provide labs and firms with the equivalent of TWI for 2025: instructions on creating, testing, and securely sharing critical workflows. Then publish these playbooks so suppliers can benefit as well. The focus should be on spreading knowledge, not just creating novelty for its own sake.

We must also acknowledge the risks. Bad actors can exploit open systems. The solution is not to close off access; it is to monitor entry points and track movements. Align the U.S. and Japan on practical definitions of research security and incident response. Share findings from security assessments. Pilot trusted research environments for sensitive datasets, with tiered access and audits. Keep collaboration as the default for low-risk science while clearly defining exceptions. Finally, consider wider cooperation. Many technologies now require international collaboration. Involve Australia, South Korea, and key European partners in modular programs—common structures with flexible elements—to expand trusted networks without compromising standards. If that sounds like aerospace supply chains, it should. They have shown us how to do this.

Conclusion. The most convincing figure in this story is the early 400 to 500 firms each year that crossed the Pacific to learn on the line. This demonstrates that policy can foster large-scale learning and that US–Japan knowledge transfer is a deliberate choice rather than a historical coincidence. We should make the same deliberate choice now—by funding modern exchanges, integrating research-security measures, and broadening circles of trusted partners. Aerospace provides the way forward: from licensed fighters to carbon-fiber wings, from supplier audits to risk-sharing design. The goal is not dependence but dependable interdependence, where both sides improve by investing in how they learn together. If we achieve this, the next decade’s breakthroughs—in semiconductors, space, climate tech, and AI—will feel less like chance and more like the result of a system that teaches, tests, and builds trust.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asia Matters for America. (2012). The 787 Dreamliner: Building US-Japan Connections for the 21st Century.

Boeing. (2017). Boeing and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries reach agreement on cost reduction for 787 production.

CSIS. (2024). How to deepen U.S.–Japan space cooperation to meet urgent security challenges ahead.

CSIS. (2025). Advancing U.S.–Japan cooperation in scientific research on the ground.

DNI (U.S.). (n.d.). Research security definition and guidance.

GAO (U.S.). (1982). U.S. Military Coproduction Programs Assist Japan in Developing Its Civil Aircraft Industry (ID-82-23).

MHI. (n.d.). Boeing 787 program—Japan work share and composite wing box.

National Academies. (1994). High-Stakes Aviation: U.S.–Japan Technology Linkages in Transport Aircraft.

Nature Index. (2025). Japan—country outputs and leading collaborators.

NSF (NCSES). (2023). Publication output and international collaboration trends.

NSF (NCSES). (2025). Discovery: R&D activity and research publications; U.S. R&D totaled $892B in 2022.

OECD. (2024). Economic Surveys: Japan 2024 (R&D as % of GDP).

Reuters. (2017). Boeing, Mitsubishi Heavy in deal to cut costs of 787 wing production (and 777X work-share context).

RIETI (2025). US-Japanese Knowledge Transfer Program in the Aftermath of WWII (Discussion Paper 25-E-092).

Trade.gov (U.S.). (2025). Japan—Aircraft and related parts (B787 Japan content share).

White House (2024, 2025). U.S.–Japan Joint Leaders’ Statements (technology, space, AI, economic security).

Comment