Fair Trade for a Fast Transition: Why Chinese EV tariffs are a necessary bridge to real cooperation

Input

Modified

Chinese EVs are cheaper due to scale, supply chains, and subsidies Targeted EU tariffs and price floors correct subsidy-driven undercutting Link trade defense to localization, skills, and investment to protect competitiveness

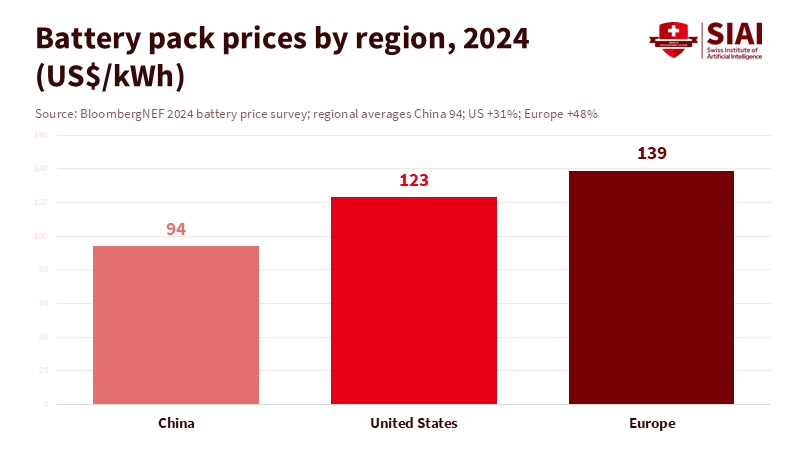

Europe's electric vehicle debate presents a false choice between green progress and fair competition. It's neither of those. Consider this sharp fact: in 2024, average battery pack prices in China dropped to about $94/kWh, while those in Europe were about 48% higher. This price difference can mean several thousand euros per car before adding logistics, profits, and dealership costs. The impact appears in trade. In 2024, China made up 40% of global electric car exports—approximately 1.25 million vehicles—while around 60% of the EU's electric car imports came from China. Even after the EU imposed final countervailing duties on Chinese battery electric vehicles (BEVs) in late 2024, China's price edge persisted due to its scale, dense supply chains, and, yes, state support. These measures are not simply about protectionism. They are tools to address price differences caused by subsidies while Europe builds the capacity needed to compete in clean technology.

Why Chinese EV Tariffs Are a Fair Response

In October 2024, the European Commission decided on countervailing duties on BEVs made in China for five years: 17.0% for BYD, 18.8% for Geely, 35.3% for SAIC, 20.7% for other cooperating firms, and 7.8% for Tesla Shanghai (subject to individual review). These duties add to the EU's standard 10% car tariff. The Commission concluded that China's EV value chain benefits from unfair subsidies, and these measures are needed to protect EU producers. Although China has challenged this at the WTO, that legal dispute does not change the key finding: subsidies—cheap financing, discounted land, and fiscal support throughout the battery, materials, and vehicle chain—distort the market. Therefore, countervailing duties are the standard response in such cases. They are targeted, time-limited, and can be reviewed—this reflects the nature of rule-based trade defense.

Europe is not acting alone. Chinese producers are facing significant domestic overcapacity, which is pushing them to export across the auto and battery industries. Reports from Reuters this year noted that capacity is almost double recent Chinese output, amid severe price competition. When this situation meets lower input costs—including battery cells priced well below global averages—the wave of exports is unavoidable unless market access comes with fair trade rules. Tariffs do not “stop EVs”; they adjust their prices to account for state support. This is not a retreat from climate goals. It is how Europe keeps the EV competition sustainable rather than a sprint that harms its own industrial base.

What Chinese EV Tariffs Can and Cannot Fix

Tariffs can reduce—but not eliminate—the price gap. Studies in 2025 suggested that a 45–55% surcharge might be necessary to fully close the average price difference between China and Europe across various segments. However, the EU's final rates, even when combined with the 10% Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariff, remain below that range for many exporters. As a result, affordable Chinese models will still attract buyers, and market shares will likely continue to shift, especially in price-sensitive segments. The International Energy Agency points out that Chinese electric-car prices fell about 30% in 2024, while prices in Europe and the United States dropped by only 10–15%. This ongoing price decline and product development in China remain strong forces that no single measure can counter.

Nor can tariffs instantly fix Europe's scale problem. Supply chains take years to develop. However, these measures give Europe more time to grow its battery production, streamline permitting, and increase the number of competitive models. They also prevent straightforward arbitrage, where companies build in China and sell in Europe. That situation exists. Volkswagen has said it can develop and manufacture an EV in China for up to 50% less than it would cost elsewhere, thanks to shorter development cycles and more concentrated supplier networks. Without trade defense, even European brands might feel pressured to move development offshore to capture those savings, then bring finished cars back. That model might support a company's profits but undermines Europe's entire upstream ecosystem—tooling, software, power electronics, and the associated learning experiences.

Designing Chinese EV Tariffs That Drive Fair Competition

Tariffs should be part of a larger, rules-based solution. Building on this, the Commission is already testing a second strategy: minimum price agreements. In April 2025, Brussels and Beijing agreed to consider enforceable minimum import prices for Chinese EVs as a possible alternative to some duties. An effective price floor can prevent subsidy-induced underpricing while allowing trade to continue. It must be high enough to avoid harm, specific enough to prevent evasion through re-invoicing or model changes, and auditable across various brands, including European ones produced in China. Recent reviews of tariffs on Volkswagen EVs made in Anhui illustrate how such agreements could work in practice—if they are as effective in removing subsidy effects as the current duties. That is the standard to meet.

Second, Europe should link trade defense measures to actual investments in the economy. Chinese manufacturers are localizing in response to tariffs. BYD plans to build factories in Hungary and Turkey; timelines differ, but the trend is evident. Localizing is beneficial if it integrates technology, generates jobs, and adheres to environmental regulations. It becomes problematic if Europe turns into an assembly point with limited local contributions. Therefore, any market-access agreements should be tied to verifiable local value added in batteries and power electronics, adherence to EU labor and environmental standards, and technology transfer to European suppliers. This strategy avoids overly broad, WTO-risky local content requirements while achieving similar results through contract conditions. It also protects small and medium-sized enterprises that support the foundation of final assembly, thereby fostering long-term competitiveness.

Cooperation After Chinese EV Tariffs

A lasting agreement will require acknowledging two realities simultaneously. First, China's EV success is not solely due to subsidies. It results from rapid product development, dense supply chains, and learning processes that drastically lower costs—battery pack prices near $94/kWh in 2024, LFP cell prices around $50–55/kWh at times, and platform reuse that shortens development times. Second, these advantages were strengthened by policy support across the supply chain, which the EU has legally documented. Fair trade means factoring that support into market access. Countervailing duties and potential price agreements serve this purpose. They are not barriers; they are pathways to better rules.

For educators and training leaders, the implications are significant. Curricula in engineering, data, and manufacturing should focus on the “EV stack”: power semiconductors, motor control software, battery management, thermal systems, and cost analysis. Business schools should teach procurement strategies within price agreements, covering compliance, audit trails, and supplier diversification. Vocational programs should develop skills for battery cell formation, pack assembly, quality analysis, and recycling logistics. For administrators, innovative procurement can foster local ecosystems: structure tenders to reward verified EU value added, lifecycle emissions, and service networks rather than just introductory pricing. Policymakers should link trade defense measures with financial support for gigafactories and power-electronics hubs, expedite grid connections for industrial sites, and implement “use it or lose it” policies for public financing to maintain project timelines.

Critics may argue that tariffs hinder the transition to green technology. The data do not back that claim. Global electric car exports surged nearly 20% in 2024; imports now account for almost one-fifth of global EV sales. China remains the top exporter, and Europe is also a net exporter—its EV exports exceeded 800,000 units in 2024. The question isn't whether EVs will spread; they surely will. The critical question is whether Europe can maintain the industrial capacity to produce them locally at scale. Reasonable Chinese EV tariffs, coupled with enforceable price agreements and investment conditions, help ensure that the answer is affirmative.

Returning to the initial fact: the battery price gap is substantial and real. It stems from scale, competition, and subsidies that drive costs lower than what market forces alone would allow. Europe's countervailing duties address this reality rather than distort it. The next step is a complete deal: minimum prices sufficient to offset the effects of subsidies, strict rules to prevent trans-shipment and fraudulent invoicing, targeted access for models that localize significant value in Europe, and a clear path for joint platforms that meet European standards. If Beijing seeks cooperation, this is the way forward. If Europe wants to achieve both environmental gains and industrial strength, it must maintain that stance—firm, fair, and open to genuine partnerships. The transition will be measured not by how quickly the initial wave of imports arrives, but by whether Europe continues to produce the subsequent waves at home on competitive terms.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

BloombergNEF. (2024, December 10). Lithium-ion battery pack prices see largest drop since 2017, falling to $115/kWh. (Regional average: $94/kWh in China; U.S. +31%; Europe +48%).

Bruegel. (2025). A smart European strategy for electric-vehicle investment vis-à-vis China. (Notes Commission openness to minimum import price commitments).

Coface. (2025, March 11). Electric vehicles: competition between China and Europe. (Estimates a 45–55% surcharge needed to bridge the price gap).

European Commission. (2024, Oct. 28). EU imposes duties on unfairly subsidised electric vehicles from China (Press Release IP_24_5589). (BYD 17.0%; Geely 18.8%; SAIC 35.3%; Tesla Shanghai 7.8%; others 20.7%).

European Commission / Access2Markets. (2024, Dec. 12; updated 2025). EU Commission imposes countervailing duties on imports of BEVs from China (Implementing Regulation 2024/2754; five-year duration).

IEA. (2025). Global EV Outlook 2025 (Executive summary and trade sections: China 40% of global EV exports in 2024; EU net exporter; 60% of EU EV imports from China; China price declines ~30% vs 10–15% in EU/US).

Reuters. (2025, Apr. 10–11). EU and China to look into setting minimum prices on Chinese EVs (Commission confirms exploration of price undertakings).

Reuters / FT. (2025, Nov.–Dec.). Volkswagen review and cost claims for China-developed EVs (EU reviewing tariffs on VW’s China-built EVs; VW says developing in China can be up to 50% cheaper).

Reuters. (2025, Sept.). China auto overcapacity and export push (Excess capacity and price pressure in China’s auto sector).

WTO. (2024). DS630: EU — Definitive countervailing duties on BEVs from China (China requests consultations).

Comment