Rethinking Household Risk: Why the Interest Coverage Ratio, Not DTI, Should Guide Policy

Input

Modified

DTI misreads risk; it ignores cash-flow strain Sweden shows the interest coverage ratio tracks stress while assets preserve solvency Center policy and education on ICR, use counter-cyclical amortization, and curb high-cost credit

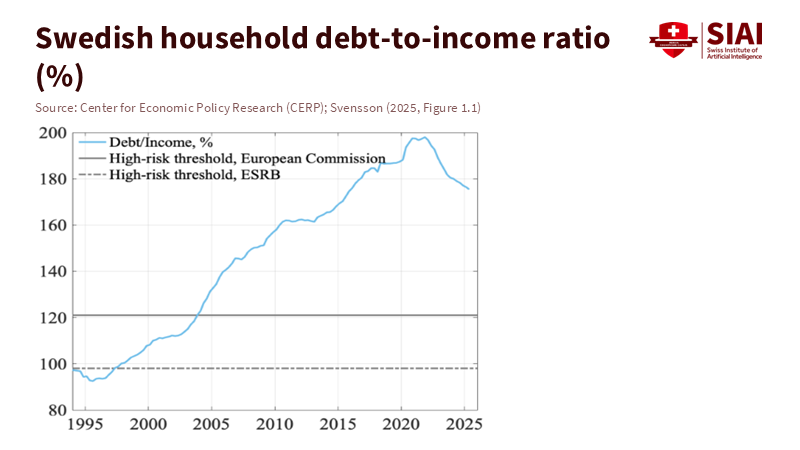

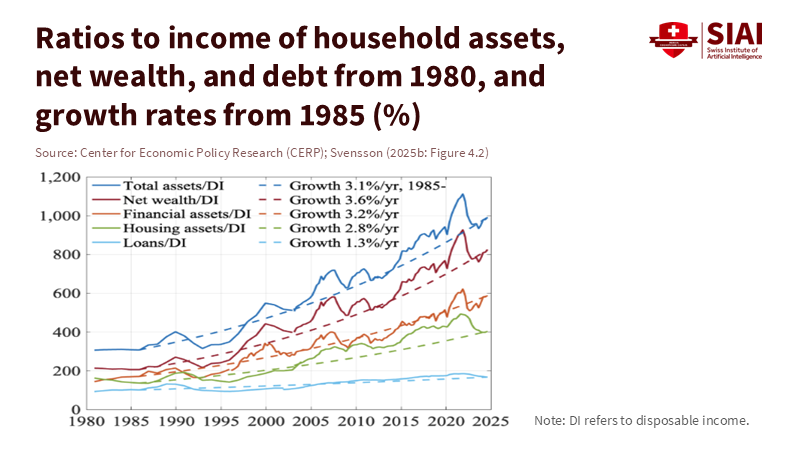

Sweden provides a clear example of how we should view debt risk. In two years, household interest payments doubled from 3.7% of disposable income to 7.6%, the highest level in the EU at that time. Yet in 2024, Swedish households had net wealth about five times their debts. Mortgage rates eased from a peak near 4% in 2024 to about 3% by August 2025, reducing the pressure once more. What can we learn from this combination of high assets, fluctuating mortgage costs, and a sharp but reversible cash flow squeeze? We need to stop using the debt-to-income ratio as our primary risk measure. It reveals little about cash strain when rates change, and even less about solvency when assets are substantial. The interest coverage ratio, which shows the portion of income used to pay interest, reflects the stress families experience, how quickly that stress can change, and when a shock becomes risky. This should be the key measure in policy discussions.

Why the interest coverage ratio is better than debt-to-income for assessing risk

The debt-to-income ratio (DTI) is a static figure. It compares a fixed amount of debt to a year's income. Still, it overlooks two critical factors that drive real risk: the current cost of debt and the liquidity of future assets. The interest coverage ratio (ICR), on the other hand, fluctuates with changes in interest rates. It shows how much cash households must spend each month to service their loans. In Sweden, where most new mortgages reset quickly, the ICR increased rapidly as policy rates rose, and it should decrease as rates fall. This is how risk appears and diminishes in household budgets. It also allows us to compare households with the same DTI but varying rate exposures and financial buffers. A high-income tenant with no assets and a variable loan can face more ICR strain than a low-income homeowner with significant, liquid savings.

Aggregate data support this shift. The Bank for International Settlements monitors a household debt-service ratio that includes both interest and scheduled principal. In early 2024, Sweden's household debt-service ratio was near historic highs, then dropped as rates eased, settling at around 12–13% of income by the third quarter of 2024. The message is clear. Cash-flow pressure, not the total amount of debt, drives the immediate economic impact on households' spending. When the interest coverage ratio rises, consumption weakens; when it falls, demand increases. DTI alone misses this timing and mechanism.

Sweden's financial reality: assets, buffers, and cash flow

Sweden's households have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Net wealth is significantly greater than debt, and this gap has grown over time. In 1985, household assets minus debts were roughly double the level of debt; by 2024, they were about five times the debt level. Such high solvency should make us cautious about blunt measures that only target DTI. This also explains why Swedish consumption slowed as the interest coverage ratio spiked, without triggering a wave of forced sales or defaults. The solvency cushion was present. It was liquidity pressure, not insolvency, that caused the damage. This resilience is a testament to the effectiveness of the proposed policy shift.

Cash-flow dynamics further illustrate this point. Mortgages account for about 80% of household borrowing, and Swedish loans adjust quickly: 89% of new mortgages in the first half of 2024 had variable rates. As policy rates rose, household interest-to-income ratios reached multi-year highs. When policy rates eased and incomes recovered in 2024, these ratios dropped for new borrowers. This cycle first appears in the interest coverage ratio, not in DTI. It is also evident in the housing market: prices fell more than 10% from the early-2022 peak, then rose about 3% through 2024. The market adjusted. Household budgets were strained, but not broken. This is expected when solvency is strong yet liquidity is tight, and it's precisely why ICR should take precedence.

From households to firms: using the interest coverage ratio as a standard benchmark

The concepts of solvency and the interest coverage ratio are well known in the corporate world. Sweden's corporate interest-to-income ratio more than doubled from 2022 to late 2023. Banks, investors, and regulators viewed this increase as a warning and adapted their risk assessments. We should apply the same analytical standard to households. The household ICR indicates when a rate shock will reduce consumption, while the household debt-service ratio adds the repayment burden. Together, they provide a clearer picture of near-term stress than any income-based debt measurement. They are also scalable across different countries and economic cycles, demonstrating their adaptability and reliability.

This shared benchmark also clarifies distributional risk. Sweden's regulators report that 83% of new mortgage borrowers amortize, and fewer new borrowers now exceed the 450% DTI threshold, a key measure used to assess the risk of high leverage. At the same time, unsecured consumer credit has caused more payment issues, with more households receiving 'orders to pay' from the Enforcement Authority in 2024. The point isn't that household debt is 'too high.' It's that high-cost, unsecured loans can significantly raise the interest coverage ratio for the most vulnerable families. In a country with strong solvency, that's where stress concentrates. Policy should address this.

Policy recommendations that focus on liquidity, not leverage

What should regulators, central banks, and educators do? First, make the interest coverage ratio the primary focus. Report it monthly for new mortgages and quarterly for the overall stock, and break it down by rate-fixation periods and income levels. Sweden already tracks related measures, and the EU has highlighted the surge in interest burdens from 2021 to 2023. A clear ICR series would improve risk warnings and reduce the urge to prioritize DTI measures that miss the crucial points. Second, stress-test households as we do firms: what happens to the ICR if rates rise by 100 basis points or fall by 150 basis points? If incomes dip by 2%? If utility bills rise in winter? The answers can directly inform macroprudential policies, potentially leading to more effective risk management and improved financial stability.

Third, adjust regulations to focus on cash-flow resilience. A commission in Sweden has proposed easing some borrowing and repayment rules to help first-time buyers, along with a cap of around 5.5 times gross income. This approach makes sense only if it includes an ICR-based test that is harder to manipulate and more responsive to rate risk. Amortization buffers should act counter-cyclically. When the interest coverage ratio rises across the economy, automatic amortization breaks for low-risk borrowers can quickly free up cash without increasing long-term debt. When ICR falls, amortization should increase. Targeted actions against high-cost unsecured loans, where Sweden has seen the most payment issues, should run in parallel with this.

Fourth, improve the data. To create liquidity-focused policy, better and faster asset and liability records are needed. Sweden's official statistics provide solid data on debt and interest burdens, but there are still gaps in liquid asset information. The OECD has called for a more complete asset register, with privacy controls, to ground policy in real balance-sheet data. This upgrade would help determine where a high DTI is harmless due to substantial assets and where a low DTI is risky because the interest coverage ratio is already tight. It would also assist schools and universities in tailoring financial education to actual household risk, rather than abstract averages.

For educators, the implications are practical. Teach students and adult learners to calculate their personal interest coverage ratio and monitor it monthly, as firms do with their debt-service coverage ratio. Highlight the rate-reset risk of variable loans and the importance of liquid buffers. Demonstrate how a one-point change in mortgage rates impacts cash flow more than a five-point change in DTI. In teacher training and business school curricula, update case studies: contrast a young professional with a high DTI and substantial savings with a mid-career borrower with a modest DTI and no liquidity. The ICR reveals who is vulnerable. This skill is essential for consumer protection.

For university and school administrators, use the same approach for institutional finance. Monitor the campus interest coverage ratio on floating-rate debt and leases. Stress-test against enrollment decreases and spikes in utility costs. Use findings to time capital projects and build cash reserves that adjust with rate cycles. The same applies to student aid. Suppose the goal is to reduce drop-out risk when rates rise and rent increases, target grants and emergency support to students whose household ICRs are most at risk. This is a better predictor of distress than family DTI.

For policymakers, the cross-sector perspective is crucial. Sweden's household ICR increased with rising rates and is decreasing as they fall. Corporate interest burdens reacted even more quickly. In both situations, liquidity, not leverage, drove the short-term economic impact. DTI-based rules can still have a role, but they should serve as a guideline, not the primary focus. The main focus should be on the interest coverage ratio. Set macroprudential tools to keep it within a safe range. Allow amortization to vary counter-cyclically. And concentrate oversight on unsecured consumer credit practices that intensify cash-flow stress beyond their size.

The Swedish example also shows how quickly conditions can change. In 2024, household interest-to-income ratios reached multi-year highs. By mid-2025, mortgage rates on existing loans had fallen about one percentage point from their peak. House prices stabilized, and new borrowers' cash ratios improved. Net wealth remained high relative to debt. None of this erases the difficulties of 2023, but it shows that risk diminishes as the interest coverage ratio drops. Policy should be flexible enough to respond in both situations—tightening when cash-flow risks increase and loosening when they decrease. This is the essence of a liquidity-focused framework.

The significant issue was not the overall size of Swedish debts, but how much income was consumed by interest payments at the peak. As that burn rate decreases, risk falls. Solvency, maintained by substantial asset holdings, was never the weak point. The weak point was liquidity under rapid adjustment. This is why a policy framework led by the interest coverage ratio is safer, fairer, and more effective. It targets the stress that actually reduces spending while allowing households with high assets and stable cash flow to borrow and invest. We should phase out DTI as the primary metric. Keep it available, but move it to the background. Doing so will reduce one-size-fits-all constraints on households, allow schools and firms to plan with a clearer understanding of risk, and enable macro policy to focus on the numbers that truly matter when conditions change.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). "Debt service ratios (DSRs): methodology and data." Accessed November 2025.

European Commission. In-Depth Review: Sweden (Institutional Paper 277, March 2024). Interest payments rose from 3.7% to 7.6% of disposable income, 2021–2023.

Finansinspektionen. The Swedish Mortgage Market (Report summary and April 2025 PDF). Variable-rate share high; interest-to-income and debt-service ratios for new mortgagors fell in 2024.

Finance Sweden. The Mortgage Market in Sweden – October 2024. 89% of new mortgages had variable rates in H1 2024; household interest ratio near 15-year high in 2023.

IMF. Sweden: 2024 Article IV Consultation. Household interest expense reached about 8% of disposable income in late 2023.

OECD. Economic Survey of Sweden 2025. On data gaps in liquid asset records and the case for a centralized, privacy-safe register.

Reuters. "Swedish government commission recommends easing mortgage repayment rules" (Nov. 4, 2024). Proposal includes LTV to 90% and income cap near 5.5x.

Sveriges Riksbank. Financial Stability Report 2024:2. Mortgages ≈ 80% of household borrowing; 2024 housing prices +3% YTD; ≈10% below early-2022 peak; rise in payment injunctions tied to unsecured credit.

Sveriges Riksbank. Financial Stability Report 2024:1. Corporate interest-to-income ratio rose from 4.6% to ≈11% by end-2023.

VoxEU/CEPR. "Swedish household debt is not too high: Look at solvency and liquidity, not debt-to-income" (2025). Net wealth ≈ five times debt in 2024; average outstanding mortgage rates eased to ~3% by Aug. 2025 from a ~4% peak in 2024.

Comment