Building an ASEAN Regional Stability Fund for the Next Crisis

Input

Modified

ASEAN needs its own stability fund to protect trade during crises Europe shows that regional firewalls boost confidence An ASEAN-led design would secure faster, fairer support

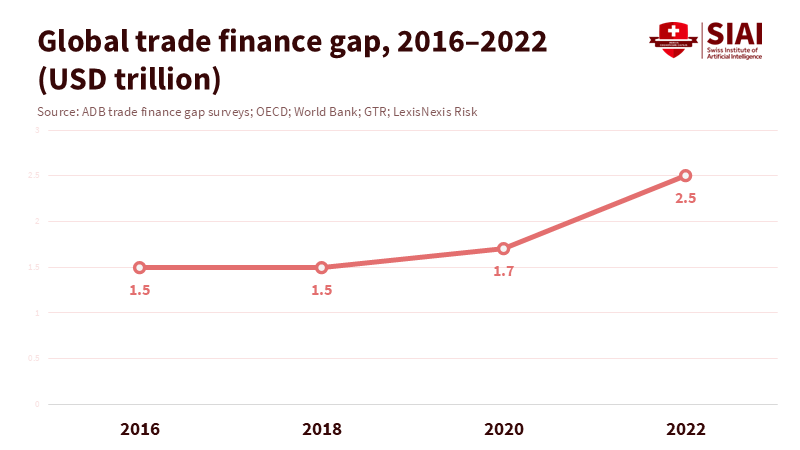

In 2022, the global trade finance gap reached about US$2.5 trillion. This gap measures the difference between what firms need to trade across borders and what banks can offer. A large share of this shortfall is in Asia, particularly in ASEAN. More than 70 million small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for over 95 percent of firms in the region and create most jobs, yet they consistently receive inadequate trade finance. The numbers illustrate the problem, but the underlying issue is political. ASEAN lacks a dedicated ASEAN regional stability fund that can respond quickly when liquidity dries up, supply chains stall, or market confidence wanes. Instead, the region relies on a mix of global arrangements and “ASEAN+3” partnerships. It depends on outdated memories of IMF programs from 1997 and makeshift credit lines. While this setup has prevented crises from escalating, it has not removed the stigma tied to external conditions. Nor does it address today’s trade finance challenges. The next stage of ASEAN integration holds promise, as the region's ability to move beyond crisis management and establish a permanent regional safety net to keep trade and SME credit flowing is within reach through the creation of the ASEAN Regional Stability Fund.

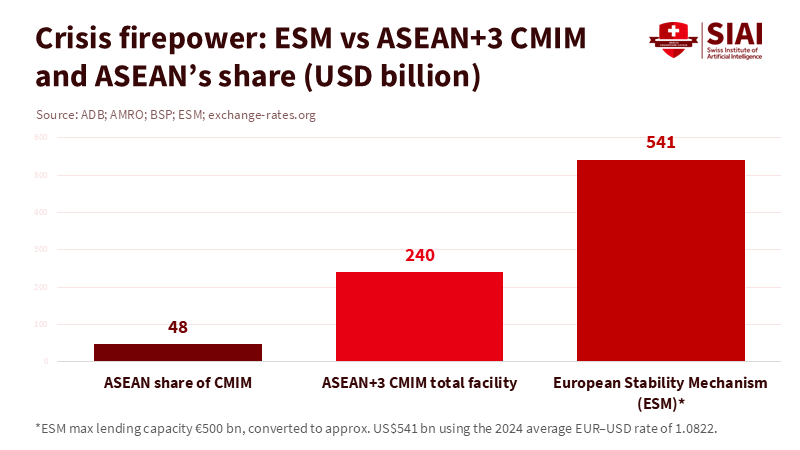

Reframing the discussion around an ASEAN regional stability fund requires a shift from traditional balance-of-payments rescues to building market confidence in everyday trade. ASEAN merchandise trade hit roughly US$1.8 trillion in the first half of 2024, an increase of 6.4 percent from the previous year’s decline. That volume relies on short-term financing that can vanish when interest rates rise or geopolitical tensions increase. Meanwhile, ASEAN leaders have endorsed a new five-year strategy to enhance financial integration and aim to establish the bloc as the world's fourth-largest economy by 2045. Still, the economic stability aspect of this goal appears weaker than in Europe. Europe has a permanent rescue fund with a lending capacity of €500 billion that supports its monetary union. To build confidence in its own integration plan, ASEAN needs a local facility that can provide timely aid to member states and their banking systems when trade finance diminishes.

Learning from Europe’s crisis funds without copying them

A good reference for establishing an ASEAN regional stability fund is Europe’s crisis response system: the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and its permanent successor, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). These were created to address the euro area debt crisis and can use various tools, including sovereign loans, bank recapitalization, and secondary-market bond purchases. The ESM’s maximum lending capacity of €500 billion is supported by €700 billion in subscribed capital, of which about €80 billion has already been paid. This capital base, combined with strict governance and a focused mandate, has allowed the ESM to maintain its AAA credit rating and borrow cheaply, even in tough times. ASEAN doesn’t need to replicate this model exactly. Still, it does require similar key elements: reliable capital commitments, strong regulations to prevent moral hazard, and sufficient resources to enable markets to trust that the fund can make a real impact.

The starting point for ASEAN is better than it may seem. ASEAN+3 already has the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation (CMIM). This regional currency swap arrangement has grown over time to US$240 billion. It includes an independent surveillance body, the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO), which could play a crucial role in the governance and oversight of the proposed ASEAN regional stability fund. AMRO recently estimated that, together, the ASEAN+3 economies have about US$8.6 trillion in potential crisis-fighting resources, including both global and regional safety nets. However, CMIM has never been activated, and its design is still closely tied to IMF involvement, reminding many of the conditionality from the 1997 crisis. An ASEAN regional stability fund should be developed as a complementary layer. It would focus on trade-related shocks and liquidity provision, operating on a smaller scale but with tools directly aimed at SMEs. Instead of waiting for a full-fledged balance-of-payments crisis, the fund could back export credit agencies, guarantee SME trade loan portfolios, or support banks’ letters of credit when risk appetite dwindles.

Turning great-power rivalry into insurance for ASEAN

Any practical plan for an ASEAN regional stability fund must take into account geopolitical realities. China and Japan will not passively accept an ASEAN-controlled tool that diminishes their influence. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), often seen as a Chinese-led initiative to reshape global finance, has been increasing its cooperation with other regional banks. In April 2024, the AIIB and the ESM renewed a memorandum of understanding to work more closely on global challenges, linking the AIIB’s infrastructure goals with the ESM's financial stability mission. AMRO has also established a strategic partnership with the Arab Monetary Fund to enhance the global financial safety net. These moves indicate that regional funds are not exclusive groups; they are becoming part of a broader network of crisis response facilities. ASEAN can use this trend to its advantage.

While the proposal for an ASEAN regional stability fund is promising, it is not without its challenges. The fund's success will depend on the willingness of major partners to co-finance it under ASEAN’s terms. One approach could be to establish a core capital base funded by ASEAN members, along with additional layers of callable capital and guarantees open to Japan, China, Korea, or even the AIIB and other regional funds. In return, ASEAN would offer co-branding and shared project initiatives while keeping governance centered on an ASEAN-majority board and a clear legal agenda. If China wants to demonstrate that the AIIB can support trade resilience, it could bid to contribute capital or guarantee on transparent terms. If Japan seeks to reinforce its image as a reliable regional lender, it could do so as well. However, this setup could also lead to geopolitical tensions and competition, potentially undermining the fund's objectives. It is crucial to manage these risks and ensure that the fund strengthens regional cooperation rather than dividing it.

Governing an ASEAN regional stability fund for trust

Establishing the governance of an ASEAN regional stability fund is just as crucial as determining its financial scope. The memories of the 1997 Asian financial crisis linger because many people associate crisis lending with strict, externally enforced conditions and sudden cuts to social spending. Any new facility will be evaluated not only on how much support it offers but also on whether its decisions are perceived as fair, transparent, and regionally owned. Here, there are helpful lessons from Europe’s experience. The ESM operates as an intergovernmental entity, but its programs are underpinned by clear legal agreements, parliamentary oversight, and a skilled staff of about 200 responsible for maintaining financial stability rather than advancing broad structural agendas. ASEAN can adopt this principle by giving the fund a focused mission: to protect trade, ensure SME access to finance, and maintain payment-system stability during crises.

In practice, this means creating robust safeguards against moral hazard and political manipulation. Access to an ASEAN regional stability fund could depend on pre-set eligibility criteria, such as compliance with regional banking standards or the use of digital trade documents to reduce fraud risks. Assistance would be temporary and focused on specific areas, such as trade credit guarantees, lines from export credit agencies, or liquidity support for banks with sound fundamentals. The fund’s credit committee should adhere to clear, published guidelines rather than engage in informal negotiations. Surveillance could be entrusted to an expanded AMRO, which would collaborate with ASEAN central banks and finance ministries to provide independent evaluations of member states’ financial situations and the condition of their trade finance systems. The more predictable and rule-based the decisions are, the more likely it is that markets will view the fund as a trustworthy anchor instead of a political tool.

From idea to implementation: what policymakers should do next

For educators and administrators, the case for an ASEAN regional stability fund is not a mere exercise in financial engineering. It concerns whether young businesses across the region can continue to participate in global value chains during the next crisis or be cut off from working capital. The international trade finance gap has stabilized at roughly US$2.5 trillion. Still, it remains vast, with around 40 percent of SMEs facing denied trade finance requests. When these gaps occur in countries with limited fiscal resources, schools, training programs, and research institutions feel the effects through budget cuts and halted investments. A regional stability fund wouldn’t solve all these issues. However, it would provide a targeted tool for alleviating financial cycles and protecting education and skill investments from harsh austerity measures during crises.

Critics may argue that existing tools are sufficient. Global institutions are bolstering targeted facilities. For example, in 2024, the International Finance Corporation and HSBC launched a US$1 billion trade finance program to assist emerging markets, directly addressing the persistent global gap. But such initiatives, while beneficial, work on a project basis and are not tailored to ASEAN’s integration goals. Others may contend that another regional fund would complicate an already crowded safety net landscape. Here, the response is intentional coordination. AMRO has urged that regional safety nets and the global system should work harmoniously and is forging partnerships with other regional funds. An ASEAN regional stability fund should connect to that framework from the start, with clear procedures for co-financing with the IMF, CMIM, AIIB, and global development banks. The aim is not to replace these entities but to provide ASEAN with a first line of defense aligned with its priorities.

The political opportunity is present. ASEAN leaders have approved a strategic plan that emphasizes financial integration, strengthened supply chains, and a collective response to geopolitical and technological challenges. Europe’s crisis funds demonstrate that once the institutional framework—capital contributions, governance, lending tools—is established, it can sustain confidence long after the last emergency. The difficulty for ASEAN is acting before the next crisis arises. If governments can agree on a step-by-step model—beginning with a modest capital base, trade-oriented tools, and governance led by ASEAN members—they can gradually develop the ASEAN regional stability fund into a foundational element of the region’s economic structure. In contrast, doing nothing would leave the region dependent on external terms when stress returns.

The initial statistic on the US$2.5 trillion trade finance gap serves as more than a reminder of unmet credit demand; it reflects the work that remains to be done for global and regional safety nets. ASEAN faces a choice: remain a passive participant in these systems or create a stronger network of its own. Establishing an ASEAN regional stability fund will require technical work, political compromises, and careful institutional development. Yet the benefits are clear: a region where SMEs can continue to export during difficult times, where education and skills investment avoid sudden cuts, and where financial crises do not reopen the wounds of 1997. Policymakers should see this effort not as a luxury but as essential infrastructure for the next phase of integration. The time to design the fund that will safeguard ASEAN’s future traders, workers, and students is now—before the next challenge occurs, not afterward.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asian Development Bank. (2023). Trade Finance Gaps, Growth, and Jobs Survey 2023. Manila: ADB.

ASEAN Secretariat. (2024). ASEAN Key Figures 2024. Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat.

ASEAN Secretariat. (2025, May 27). ASEAN unveils strategic plan to integrate its economies.

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank & European Stability Mechanism. (2024, April 22). AIIB and ESM strengthen cooperation in addressing global challenges.

Asian Development Bank & Global Trade Review. (2025, September 3). Trade finance gap stabilises at US$2.5 trillion.

ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO). (2025, October 16). Uniting regional safety nets for global financial stability.

ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO). (2025, October 15). AMF, AMRO forge strategic partnership to strengthen global financial safety net.

Bank Negara Malaysia. (2014). Enhancement of the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation (CMIM).

Banque de France. (n.d.). Crisis management mechanisms.

Beck, S. (2023). Trade Finance Gaps, Growth, and Jobs Survey 2023. Asian Development Bank.

European Stability Mechanism. (n.d.). What is the ESM’s lending capacity?

Hoffner, B. (2023). The Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization. Journal of Financial Crises.

HSBC & International Finance Corporation. (2024, December 12). HSBC, IFC launch US$1bn trade finance programme for emerging markets.

Philippine Central Bank (BSP). (2025). Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization FAQ.

Comment