Central Banks Cannot Fix Broken Pipelines: Rethinking Monetary Policy for Supply Shock Inflation

Input

Modified

Supply shock inflation comes from real shortages that rates cannot fix Central banks can limit spillovers, but fiscal and structural tools must absorb the shock Inflation control is a shared task.

When European gas prices surged above €310 per megawatt hour in August 2022, about fifteen times their level in January 2021, no change in interest rates could reopen pipelines or refill storage quickly. Yet our prevailing framework treated this situation as if central banks still wielded the primary tool against supply shock inflation. Rate hikes came swiftly. The Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation measure hit 7.3% in the summer of 2022, clearly diverging from the low and stable inflation seen in the previous decade. In the euro area, headline inflation jumped from 2.6% in 2021 to 8.4% in 2022, primarily driven by energy and food prices following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. The old narrative said that credible inflation targeting and swift rate increases would restore stability. However, this surge revealed a more fundamental issue: we have asked monetary policy to tackle problems it cannot address. Supply shock inflation is not something a central bank can eliminate on its own. It signals that the policy assignment problem itself is flawed.

The limits of inflation targeting during supply shock inflation

Inflation-targeting frameworks formed after the shocks of the 1970s were designed for a time when demand pressures posed the main threat. The central bank would set a clear target, adjust rates, and use credibility to guide expectations. For many years, this model worked adequately. However, the recent wave of supply shock inflation exposed its weaknesses. A growing body of research breaks down post-pandemic inflation into supply and demand factors. An IMF study finds that supply-driven inflation reacts strongly to oil shocks and supply chain issues. In contrast, demand-driven inflation responds more to changes in monetary policy and comes with a steeper Phillips curve. To put it simply, rate hikes work when demand is too strong. They are blunt instruments and often harmful when the issue is a lack of gas, insufficient ships, or closed factories.

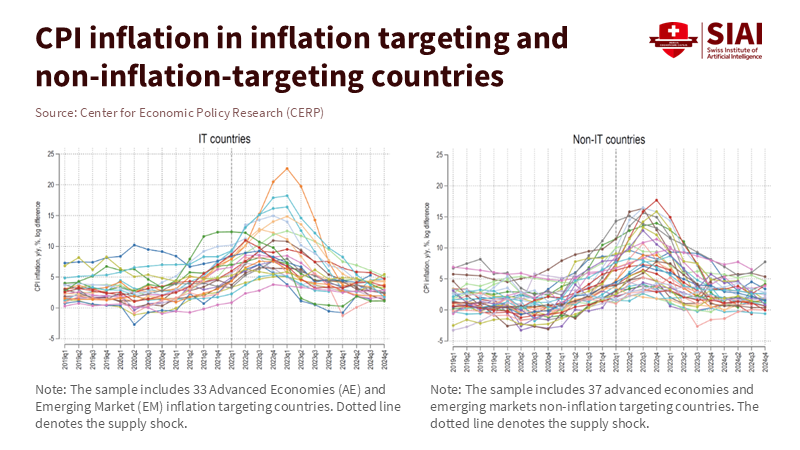

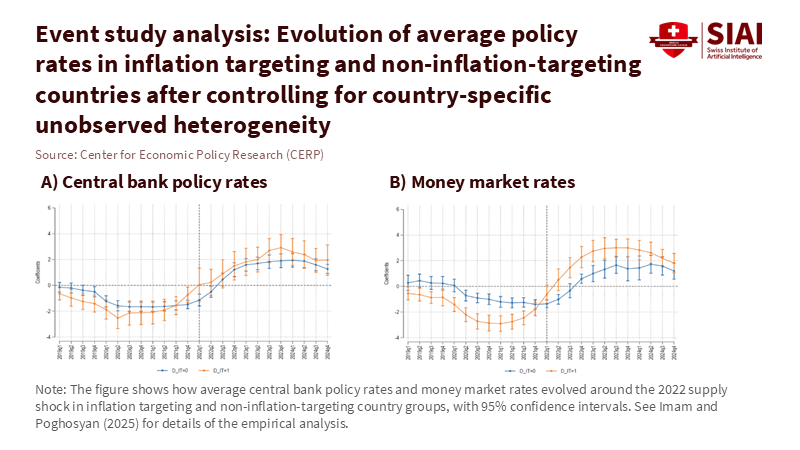

Evidence from multiple countries confirms that supply shocks contributed significantly to the inflation surge post-2020. Research in the US indicates that binding supply chain constraints account for about half of the inflation rise during 2021–2022, with tight capacity worsening the effects of earlier loose monetary policy. In the euro area, studies of the inflation spike identify energy and food as the main culprits, with these supply-side pressures leading to broader price increases. A CEPR study highlights that supply shocks primarily drove post-pandemic inflation across advanced economies. In contrast, demand shocks mainly influenced the rise in interest rates. The implication is striking. The core tools of inflation targeting address only the part of the problem they can identify—demand—while most of the pressure arises from bottlenecks, war, and energy dependence.

This does not mean monetary policy was irrelevant. Central banks still had to prevent supply shock inflation from turning into a self-reinforcing wage–price spiral. Rate hikes can prevent an energy shock from spreading to other prices indefinitely. But the experience of 2022 demonstrated that there is no interest-rate path that keeps inflation near 2% while fully safeguarding growth when gas prices rise fifteenfold. At best, central banks can ease the return to lower inflation. They cannot eliminate the real income loss from a surge in the prices of imported energy or food. For educators and students of macroeconomics, this should change how we present the textbook diagram: the policy lever that moves the demand curve is only part of the picture. The supply curve, damaged by war, pandemics, or climate shocks, cannot be restored by a central bank's will.

How supply shock inflation revealed the credibility illusion

For forty years, credibility has been the key concept in monetary policy. If households and businesses believed the central bank would keep inflation close to the target, inflation would remain close to it. This idea held up during the global financial crisis and the long period of low inflation. However, it faltered under supply shock inflation. Surveys and market-based measures show that expectations did not spiral out of control in 2022; yet actual inflation still overshot widely. Recent studies on supply shocks reveal that even when expectations remain generally anchored, significant price increases—such as energy spikes—can push individual prices above 4% and keep them elevated as the shock spreads across products and regions. Credibility can limit the second round of effects, but cannot neutralize the first.

Evidence from financial markets reinforces this point. A recent analysis indicates that as the global economy reopened in 2021, supply bottlenecks and policy factors became major drivers of inflation expectations, with supply shocks and OPEC-related energy changes driving expectations higher even before demand fully recovered. Simultaneously, aggressive tightening in the US influenced expectations but did not completely counteract supply shock inflation. By late 2025, the San Francisco Fed’s assessment of US inflation still shows significant contributions from supply factors, even as overall inflation has decreased and the job market has cooled. The message is clear. Credibility and quick tightening are beneficial, but only marginally, when the main force is a series of shocks to energy, food, and global logistics.

Public discourse has not kept pace with this evidence. Headlines still question whether the Federal Reserve has “defeated” inflation, as if supply-shock inflation were an enemy the central bank should conquer alone. This framing leads to misguided conclusions: if inflation remains above the target, the central bank must have failed. A more truthful interpretation, aligned with recent research, is that central banks did what they could without triggering severe recessions. The real shortfall lies in the broader policy approach. Geopolitical choices enabled the war and its energy repercussions; regulatory choices exacerbated supply chain weaknesses; fiscal choices determined how the shock was shared among households and businesses. Educators who continue to present credibility as the primary tool in all inflation scenarios mislead future policymakers into overlooking these other options.

Sharing the burden of supply shock inflation: fiscal and structural tools

If monetary policy cannot fully control supply shock inflation, the natural question arises: who can? The uncomfortable answer is that no single institution can. However, the energy crisis of 2022–2023 clearly showed that fiscal and structural policies are better at cushioning and reducing the real impact. For instance, EU governments announced energy support packages averaging about 2.4% of GDP in 2022–2023, which included targeted payments and wide-ranging measures to reduce prices. IMF estimates suggest that fully covering anticipated energy cost increases might have cost around €1 trillion, nearly 6% of EU annual GDP, highlighting both the magnitude of the shock and the limits of broad subsidies. These responses were often messy and poorly targeted. Still, they directly addressed the distributional impact of supply shock inflation in a way that interest rates never could.

The same reasoning applies to food and other essentials. An ECB blog recently estimated that euro area households have faced a 34% increase in food costs since 2019, much faster than overall consumer prices, with some items rising by 50% or more. This illustrates supply shock inflation in everyday life, influenced by global commodity markets and climate-related disruptions. Monetary tightening can reduce demand for non-essential items, but it does not create wheat or restore damaged farmland. Well-designed fiscal tools—such as targeted cash transfers, temporary energy and food vouchers, or windfall taxes on extraordinary profits—can protect vulnerable households without establishing ongoing subsidies. Structural policies that expedite investment in renewables, diversify import sources, and enhance grid and storage capacity can lessen future vulnerability at its source. In discussions of education policy, these instruments are sometimes seen as separate from macro policy. Instead, they should be considered essential components of any strategy to manage supply shock inflation.

For educators and administrators in economics and public policy programs, this calls for a change in how we teach and design curricula. The traditional assignment problem—using monetary policy for stabilization and fiscal policy for long-term issues—is no longer adequate for an era of persistent supply shock inflation tied to geopolitics and climate risks. Courses should illustrate how targeted fiscal aid, automatic stabilizers, and structural investments interact with interest-rate policy during supply shocks. Case studies on the energy crisis, pandemic bottlenecks, and food price spikes should be included alongside classic narratives about demand booms. Students preparing for careers in central banks, finance ministries, or education ministries must understand that stabilizing inflation under these circumstances is a collective effort. Otherwise, the next shock will again be placed solely on the central bank, resulting in predictable disappointment.

Designing a new framework for future supply shock inflation

Central banks are beginning to acknowledge this reality, even if public discourse has not yet caught up. The Federal Reserve initiated a new review of its framework in early 2025. Chair Powell has publicly stated that the existing framework “worked just fine” over the last five years. However, he also emphasizes that the Fed will consider lessons from the previous five years and remain open to new ideas. This quiet contradiction demonstrates the pressure supply shock inflation has placed on the old model. The Fed is not alone. In Europe, the ECB has revised its strategy and now openly warns that repeated supply shocks and structural changes—such as geopolitical fragmentation, climate events, and even the rise of AI—are making inflation more challenging to manage with rate policy alone. Recent IMF research on the 2022 spike also concludes that aggressive rate hikes could not solve bottlenecks and that energy and food prices dominated that episode. Gradually, the official narrative is aligning more closely with what the data has suggested for some time.

Critics will likely dispute this perspective. Some may argue that central banks caused supply shock inflation by remaining too loose for too long in 2021. Others might say that greater reliance on fiscal and structural tools invites political gridlock and risks unsustainable debt. Both concerns are valid. Monetary policy did play a role, especially in the US, where strong demand and tight labor markets added to the pressure.

The goal now is to incorporate those lessons into our teaching, learning, and policymaking. Framework reviews should formalize the idea that supply shock inflation calls for a different approach: central banks focus on preventing persistent second-round effects while accepting temporary overshoots; fiscal authorities implement targeted, time-limited support financed transparently; and structural policies accelerate diversification and green investment to lessen future risks. Education ministries and universities can support this by refreshing macroeconomics curricula, integrating cross-disciplinary courses on climate, trade, and energy security, and training future officials to think in terms of a coordinated policy mix rather than relying on a single heroic institution. If we continue to evaluate central banks based on their ability to fix broken pipelines with interest rates, we will repeatedly fail both the test and the students.

The 2022 gas spike was not just a worrying chart. It showed us that supply shock inflation operates under a different set of economic risks. Prices went up because actual resources became scarce, not because people suddenly lost faith in central banks. Even now, food prices in the euro area are still much higher than before the pandemic. This is putting pressure on the budgets of low-income households, even though overall inflation is moving back toward target levels. We can no longer act as if a single inflation target and a single policy rate are enough to handle this situation. The next approach needs to start with a clearer division of roles: central banks should keep demand and expectations stable, while fiscal and structural policies manage real shocks and protect those most vulnerable. Educators, administrators, and policymakers should see this as a reason to revise syllabi, policy documents, and institutional guidelines now. If we don't, the next round of supply shock inflation will catch us off guard again, using the wrong tools—and the social cost will be even greater.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Acharya, V. V., et al. (2025). How Do Supply Shocks to Inflation Generalize? Evidence from Disaggregated Price Data. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report 1164.

Arregui, N., et al. (2022). Targeted, Implementable, and Practical Energy Relief Measures for Households in Europe. IMF Working Paper 22/262.

Cleveland Fed (Gordon, M. V., 2023). “The Impacts of Supply Chain Disruptions on Inflation.” Economic Commentary, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Comin, D., et al. (2023). Supply Chain Constraints and Inflation. FEDS Working Paper 2023-075, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

European Central Bank (2023). “Annual Report 2022.” European Central Bank.

European Central Bank (2024). “The Dynamics of Inflation Differentials in the Euro Area.” Economic Bulletin, Box Article.

European Central Bank (2025). “Food Costs Jump by a Third for Eurozone Households Since 2019, Says ECB.” ECB Blog as reported by Financial Times.

Firat, M., & Hao, O. (2023). Demand vs. Supply Decomposition of Inflation: Cross-Country Evidence with Applications. IMF Working Paper 23/205.

Giannone, D., et al. (2024). The Drivers of Post-Pandemic Inflation. NBER Working Paper 32859.

Hajdini, I., et al. (2025). Inflation Since the Pandemic: Lessons and Challenges. FEDS Working Paper 2025-070, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Imam, P. A., & Poghosyan, T. (2025). Navigating the 2022 Inflation Surge: A Comparative Analysis of IT and Non-IT Central Banks. IMF Working Paper 25/212.

Lagarde, C. (2025). “Supply Shocks and the Future of Monetary Policy in the Euro Area.” Remarks at the ECB Sintra Forum, as summarised in Financial Times.

Luther, W. J. (2025). “Why Is the Fed Revising Its Framework?” The Daily Economy, 22 August.

San Francisco Fed (Shapiro, A., 2025). “Supply- and Demand-Driven PCE Inflation.” Data tool, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

World Bank (2023). “What Explains Global Inflation?” World Bank Research Brief.

Comment