Counting the Global Welfare Loss from Chinese Subsidies

Input

Modified

Chinese subsidies lower prices now but create domestic misallocation and cross-border distortions Importers’ short-run gains are offset by capacity loss, concentration, and volatile input shocks Targeted remedies, resilient procurement, and updated curricula can cut the global welfare loss

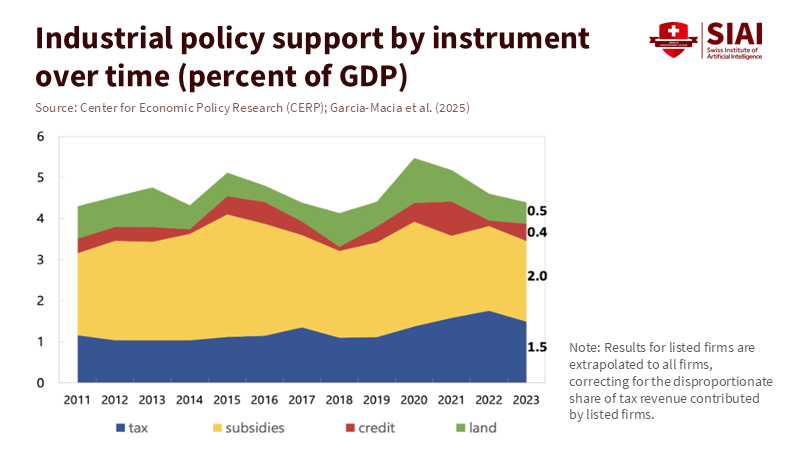

China's industrial policy is no longer just a domestic issue. It is a pressing concern that is significantly impacting home efficiency and posing a growing threat abroad. Recent estimates reveal that subsidies, tax breaks, cheap credit, and discounted land are costing China about 4% of its GDP each year. These policies are linked to a 1.2% decline in overall productivity and a potential 2% lower GDP over time. This serves as a starting point for a larger discussion. When a large economy pushes production with heavy state support, the price effects spread, capacity shifts, and other countries face suboptimal outcomes. While standard economic models predict this and educators teach it, many policymakers fail to grasp its urgency. To understand the global welfare loss from Chinese subsidies, we need to consider both aspects: cheaper imports today and the erosion of competing capacity, which raises long-term costs. The latest numbers allow us to measure this more accurately.

Global welfare loss from Chinese subsidies begins at home

The most precise starting point is within China. The latest measurement shows that industrial policy support—comprising cash subsidies, effective tax relief, cheaper loans, and discounted land—adds up to about 4% of GDP in 2023. These measures direct resources toward specific sectors and away from more productive uses. In an ideal model, resources would shift until returns are equal. However, in China's second-best reality, policy distortions keep labor and capital in less efficient areas, reducing overall productivity by about 1.2%. Over time, this can reduce GDP by up to 2% compared to a hypothetical situation without such policies. These figures are based on firm accounts, land registries, and effective tax rates over a decade. Therefore, the domestic efficiency loss is the first entry in any calculation of global welfare loss from Chinese subsidies.

This domestic misallocation has global implications, mainly when a major subsidizing country exports heavily. Research from the IMF shows that exports of subsidized products from large emerging economies grow about 8% faster than comparable non-subsidized products. The mechanism is straightforward: lower costs at home lead to lower export prices, reshaping competitive advantages. Trade data illustrate this in sectors where Chinese support is most pronounced. This spillover is not minor; it is how local misallocation creates a global welfare loss from Chinese subsidies, redistributing surplus across borders and time.

How Chinese subsidies transmit global welfare loss

Consider electric vehicles. The European Commission imposed countervailing duties on Chinese battery EVs in 2024 after finding extensive state support. Despite the tariffs, Chinese-brand BEVs continued to gain market share in the EU in 2025. KPMG estimates reveal a lasting price difference of about 12–13% in favor of leading Chinese models in key segments. While these discounts increase consumer surplus today, they also put continuous pressure on European manufacturers, affecting their margins, investment, and sustainability—classic second-best dynamics at play when one side faces subsidized competition. In the short term, the net effect in importing countries is unclear; in the long run, the loss of production capacity becomes more challenging to reverse, increasing the global welfare loss from Chinese subsidies.

Solar energy provides an even clearer example of this mechanism. China dominates the upstream market for wafers and ingots. At the same time, module prices dropped to about ten cents per watt in 2024—levels many analysts consider unsustainable—leading to the closure or failure of European manufacturers. When the last major producer in a continent announces plans for insolvency, it represents more than just a company issue; it shifts future options for buyers and public decarbonization strategies. While cheap modules foster current adoption, they risk creating a weaker, less stable supply chain later. This trade-off illustrates a typical second-best outcome affecting other regions, contributing to the global welfare loss from Chinese subsidies through exits and consolidation.

Short-run gains, long-run capacity risk

Consumers in importing countries benefit when subsidized goods are inexpensive. This is evident in the price differences between EVs and the decline in the levelized cost of solar energy. However, the long-term outlook changes once significant market segments consolidate around one subsidizing supplier. Two critical factors highlight this risk. First, rebuilding lost capacity is costly. The U.S. attempts to bring semiconductor production back home illustrate this. For instance, one project—TSMC Arizona—required a $6.6 billion federal grant, up to $5 billion in loans, and a $65 billion private investment. Similarly, Intel’s multi-state build needed approximately $8 billion in grants and substantial loans. These expenses are not just comparable to old plant costs; they indicate the enormous public spending necessary to restore strategic capacity once it departs. In terms of welfare, tomorrow’s costs of recreating production can outweigh today’s savings for consumers, thereby increasing the global welfare loss from Chinese subsidies.

Second, concentrated supply amplifies price fluctuations. In August 2025, the price of neodymium-praseodymium oxide, a key input for magnets, surged from around $63 to $88 per kilogram within weeks after a U.S. miner halted shipments to China. This move removed only a small share of supply, yet the price increased about 40%. When supply chains are tight and processing is centralized, price changes can sharply affect downstream users. This dynamic illustrates what a decade of consolidation can create: low prices during periods of excess capacity but higher costs when policy or quota issues arise. We should understand the global welfare loss from Chinese subsidies as the area under that volatility curve, not just the difference between domestic and import prices.

Policy design to minimize the global welfare loss from Chinese subsidies

The appropriate response is not broad protectionism. Instead, we need specific, time-limited, and transparent rules that minimize distortions without eliminating price competition. Europe provides early examples of this approach. The Foreign Subsidies Regulation is beginning to take effect, screening subsidized bids and requiring disclosures that reduce information gaps. This transparency in policy design reassures the audience of the fairness and equity in the trade system. Sector-specific trade-defense measures—such as those in mobile access equipment and EVs—aim to counter particular subsidy channels rather than excluding foreign suppliers entirely. The guiding principle is second-best: If a large trading partner employs extensive subsidies, the importing region should address the issue without creating a larger problem. For educators and officials, this serves as a real-world example of conditional equilibrium. Procurement rules, grant frameworks, and educational curricula should all address how to manage spillovers in a world with ongoing state support.

What does this look like in practice for schools, universities, and government bodies? First, update economics and public policy courses to treat industrial policy spillovers as an essential subject, not a minor point, connecting theory, data, and case studies on EVs, solar energy, and critical minerals. Second, refine public procurement to prioritize resilience features—such as supplier diversity, local service networks, and standardized components—ensuring that the lowest subsidized bid does not always win by default. Third, use careful trade measures alongside investments in domestic capabilities where social benefits are high and private risks are significant, with explicit end dates to avoid exploitation. Finally, develop strategies to handle price shocks: when a vital input price spikes, education technology programs, EV bus purchases, and campus energy agreements should have automatic responses that maintain service while avoiding panic buying. Each step narrows the gap between short-term savings and long-term capacity, reducing the global welfare loss from Chinese subsidies.

The situation has become clearer. China's industrial policies create an efficiency cost domestically—around 1–2% of output—and lead to international consequences through cheaper exports, capacity reductions, and price fluctuations once concentration occurs. These impacts are reflected in EV market shares, solar module prices, factory closures, and budget allocations that advanced economies are now using to rebuild capacities. This is the reality of the global welfare loss from Chinese subsidies: a series of immediate advantages, overshadowed by longer-term costs that often go unnoticed until they suddenly materialize. The solution is not to withdraw from trade but to fix the distortions through transparent screening, appropriate measures, and smarter public investment. Education systems should take the lead in teaching about this complex environment, and government bodies should incorporate it into procurement and policy design. If we do this, fewer schools, cities, and companies will be exposed to drastic changes when a sector shifts from surplus to shortage, and the global welfare bill will be smaller than it would otherwise be.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

ACEA. (2024, June 12). China anti-subsidy investigation: provisional duties. European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association.

BloombergNEF. (2024, Aug. 27). 3Q 2024 Global PV Market Outlook (module prices near $0.096/W).

European Commission. (2024, July 3). Commission imposes provisional countervailing duties on imports of battery electric vehicles from China. Press corner; Access2Markets note on definitive duties (Oct. 30, 2024).

European Commission. (2025, Apr. 28). Commission acts against unfairly subsidised imports of mobile access equipment from China.

Garcia-Macia, D., Kothari, S., & Tao, Y. (2025, Nov. 10). The hidden costs of China’s industrial policy. VoxEU (CEPR).

IEA. (2024). Solar PV Global Supply Chains (China’s >90–95% share in wafers/ingots).

IMF — Rotunno, L., & Ruta, M. (2024). Trade Spillovers of Domestic Subsidies (IMF Working Paper 24/041).

JATO Dynamics. (2025, Jan. 30). European new car market: hybrids rise; BEV pricing and Chinese brands.

KPMG. (2025). Impact of Chinese OEMs in Europe (Part II) (C-segment EVs ~12–13% cheaper).

MERICS. (2025, June 11). The EU sees early successes in using Foreign Subsidies Regulation against Chinese companies.

NREL. (2024, Aug. 20). Summer 2024: Solar Industry Update (global module price ~$0.10/W).

Reuters. (2024–2025). Various—EV tariffs coverage; China overcapacity analysis; Meyer Burger developments; NdPr spike in Aug. 2025; China 2024 vehicle exports (6.41m).

Rhodium Group. (2024). Overcapacity at the Gate; (2025) Global Clean Investment Monitor: EVs and batteries.

TSMC & U.S. Department of Commerce. (2024, Apr. 8). Announcement of up to $6.6B in CHIPS Act direct funding; up to $5B in loans; $65B investment plan. Press releases and Reuters coverage.

Comment