The Real Economics of Workweek Productivity

Input

Modified

Shorter hours raise workweek productivity only where overwork and waste are high Denmark shows pay falls when hours drop without real efficiency gains Cut low-value tasks and add smart AI, then trim hours in burnout hotspots

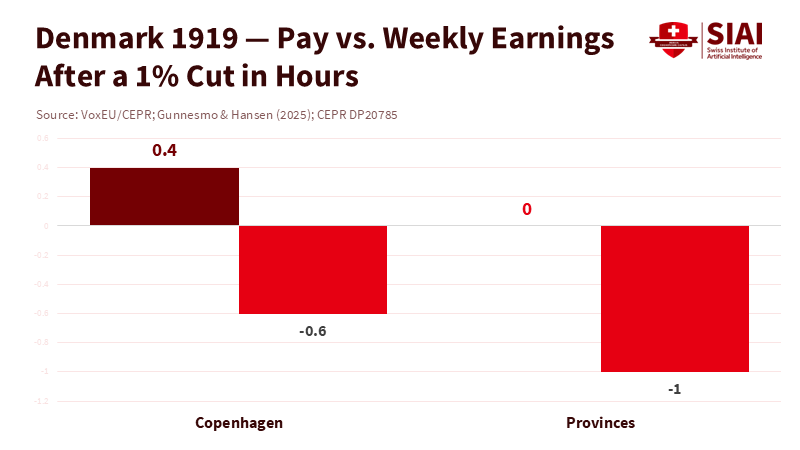

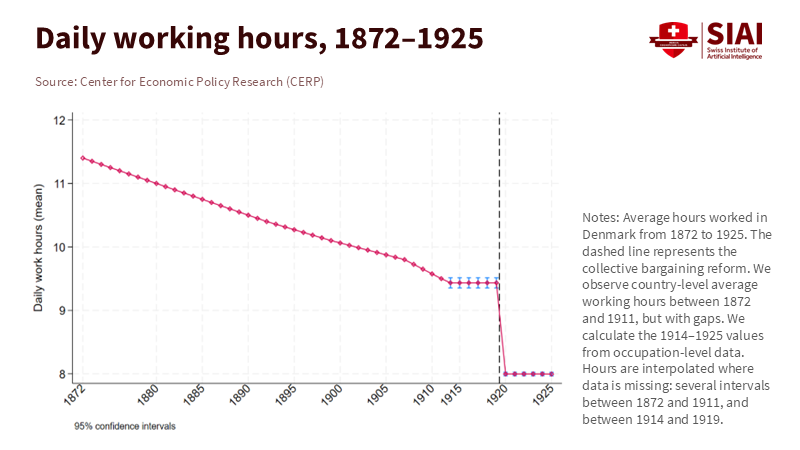

One key number highlights the tough trade-off in workweek productivity. When Denmark implemented the eight-hour workday in 1919, each 1% reduction in hours boosted hourly pay by about 0.4% in Copenhagen. However, weekly earnings still decreased by approximately 0.6%. In the provinces, earnings fell almost in line with the hours cut, as wages hardly changed. While employment did increase, output and pay per worker declined unless companies could get more from each hour of work. This historical trend serves as a warning for today’s discussions. If we shorten the workweek without increasing productivity, total output will decline, and pay will likely decrease as well. Gains in productivity from more time off do exist, but they are not guaranteed across the board. They typically appear where overwork creates issues—high turnover, frequent overtime, and costs or errors linked to health. In other cases, we risk losing income for time without gaining efficiency. The goal should not be simply shorter hours, but rather workweek productivity that aligns with the realities of each sector.

Reframing the Workweek Productivity Debate

Proposals for a four-day workweek or a universal hours cut often assume that attention improves, distractions decrease, and output per hour increases enough to offset the reduction in hours. Some experiments support this idea, particularly in environments where workers have built-in “on-the-job leisure.” A 2025 management insight summarizes research indicating that offering more real leisure outside of work can reduce wasted time during work and boost productivity. Yet these results depend on context and are most evident when distractions or low-value tasks consume time. They do not guarantee consistent returns across all sectors. Workweek productivity increases when we cut hours that contribute the least value. It declines when cuts affect hours heavily involved in teaching, clinical work, or customer service.

The economic point is straightforward. Hours yield diminishing returns, but the degree of this varies by job and by institutions such as wage-setting and scheduling. Evidence from Denmark in 1919 shows that when hours decrease significantly, pay does not fully increase, leading to lower weekly earnings—even with some hourly wage adjustments and the addition of jobs for new workers. We should expect this in 2025 as well; reductions in hours will lower total output unless companies eliminate waste, shift tasks to technology, or redesign workflows. Where the institutional framework supports complete wage replacement without efficiency increases, the benefits of employment may also disappear. To boost workweek productivity, we need to focus on where excessive labor use is the bottleneck and redesign jobs —not just the schedule.

Where Shorter Hours Raise Workweek Productivity

The best candidates for shorter hours are sectors plagued by chronic overwork and human-error issues, such as healthcare, specific construction operations, and some professional services with frequent context-switching. In hospitals, burnout is not just a term; it impacts safety and quality. A 2024 meta-analysis of 85 studies linked nurse burnout to worse outcomes, including higher medication errors, patient falls, and adverse events, along with lower patient satisfaction. In these environments, even slight declines in fatigue can boost performance per hour and help prevent costly mistakes. Overtime also predicts worsening burnout over time in longitudinal health-worker studies. These areas offer opportunities for shorter, well-designed shifts or time-off incentives that can truly enhance workweek productivity.

Evidence from large multi-firm trials supports this view. In the UK’s four-day workweek pilot involving 61 companies, revenue increased slightly (about 1.4% on average) while staff turnover dropped by 57% during the trial, and self-reported burnout fell significantly. Other reports noted a 65% decrease in sick days. These outcomes resulted from organizations that focused on redesign: shorter meetings, clearer output measures, and tools that reduce low-value tasks. Participation was primarily among service sectors with flexible scheduling and intangible outputs. The lesson isn’t that “shorter hours always work.” Instead, it’s that “a combination of good work design and shorter hours can succeed in some settings,” with the design effort crucial for increasing productivity during the workweek, not just the change in hours alone.

Another relevant point comes from experiments using leisure as a reward. When managers grant time off as a reward for good performance, workers tend to browse less during work hours and concentrate more when being paid. This effect is most potent in jobs with frequent distractions and poor process discipline. It is less effective where tasks are fixed and cannot be compressed—such as teaching time, clinical rounds, machining cycles, or peak-hour service. Therefore, the policy implication should target reductions in hours when marginal hours contribute the least value and when fatigue leads to significant error costs. This approach allows us to convert leisure into improved workweek productivity instead of reduced weekly output.

When Shorter Hours Reduce Output: Education’s Tight Constraint

Education is where the blanket promise often falters. Schools have fixed contact time requirements, even as student complexity increases. TALIS 2024 reports that, across OECD systems, an average of 73% of teachers face academically diverse classrooms, and many report a significant number of low achievers. In these situations, an overall reduction in hours doesn’t make the job smaller; it shortens the day. Without careful redesign, the likely outcome is fewer contact minutes, rushed preparation, and the burden shifting to unpaid time—hardly an improvement in workweek productivity. This is not to say that overwork isn’t a problem in education. Instead, it signals that improvements come from reworking the load, not from promising universal time off.

Teacher shortages further complicate the issue. OECD reports reveal an aging workforce and increasing vacancies in several education systems. Media and union surveys indicate many teachers are putting in large amounts of unpaid overtime; some national snapshots show teachers working well beyond their assigned hours, much of it on administrative tasks. In this environment, cutting the workweek without reducing the workload formalizes an existing squeeze. The solution lies in eliminating low-value tasks and preserving contact time. This means reducing paperwork, simplifying assessment processes, and automating routine administrative tasks before we change schedules. We should consider workweek productivity as the goal: achieving more learning per paid hour by streamlining preparation and grading, and providing better-targeted student support.

There’s a practical technology aspect here. Generative AI and related tools can currently automate substantial parts of planning, formative feedback, email triage, and data entry. Reliable estimates suggest that today’s AI could automate activities that consume 60-70% of time in many knowledge workflows. However, this doesn’t mean jobs will disappear. The OECD finds little evidence so far of widespread job losses due to AI. Instead, suppose systems invest in training, safeguards, and workflow redesign. In that case, they can initially free up hours and then discuss schedule changes. If the reverse happens, the pressure to cut costs may lead leaders to reduce services or hasten the replacement of human tasks with software in blunt ways. To enhance workweek productivity in education, we should focus on reducing administrative duties before decreasing hours.

Policy Design for Workweek Productivity in the AI Transition

Policy should start with diagnostics instead of headlines. Look for the three warning signs that shorter hours can bring benefits: high turnover, extensive overtime, and health or error indicators that carry real costs. Research highlights that very long work schedules increase the risks of heart disease and stroke; even outside of healthcare, sustained overwork raises the chances of injuries and absenteeism. In these critical areas, reducing hours while redesigning shifts and tasks can lead to higher output per hour and lower hidden costs. This is what workweek productivity looks like. In areas outside these hotspots, begin by cutting low-value activities through process improvements and targeted technology, then assess whether the remaining tasks can be done effectively in fewer hours.

Next, ensure that incentives align with outcomes rather than mere presence. The lesson from Denmark reminds us that significant mandated hour reductions are not without cost, and that wage-setting and bargaining rules determine who feels the impact. The modern equivalent is to make any reduction in hours dependent on measurable efficiency improvements: fewer handoffs, less rework, fewer mistakes, and faster cycle times. In sectors with fixed service hours—like education, transport, and emergency services—consider staggered four-day rotations instead of sweeping closures, and pair these with AI-assisted tools where evidence supports their use. Be cautious of substitution risks as well. As wages rise alongside reduced hours, the justification for automating tasks becomes more compelling. Analysts estimate that half of current work activities could be automated by the mid-2040s, with specific high-exposure jobs experiencing changes sooner. This highlights the importance of enhancing workweek productivity. If we identify the gains within the work itself, we can maintain both wages and quality. If we fail to do so, technology will fill the gap—and perhaps more.

The most accurate interpretation of the evidence is both cautious and optimistic. Careful, because Denmark’s history shows that reducing hours without a comprehensive redesign lowers weekly earnings and total output for many workers. Hopeful, because when overwork is the main issue—when burnout, overtime, and errors accumulate—shorter and more thoughtfully designed schedules can improve workweek productivity and pay for themselves. The best approach is to plan carefully before acting. Start with diagnostics. Eliminate low-value work through simple process improvements and properly managed AI. Protect the hours that matter for learning, safety, and service. Then cut the unnecessary hours. If we follow this order, we can give people real time back without reducing their pay. If we do it the other way around, we risk a smaller pie and faster automation. A century after the eight-hour day, the challenge remains the same: design institutions and workflows so that the next hour we eliminate is the least productive one. This is how we create more value from fewer hours and make workweek productivity a meaningful goal.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Autonomy (2023). The results are in: the UK’s four-day week pilot.

California Management Review (Vogelsang, T.) (2025). “Give Employees More Leisure to Boost Productivity.” CMR Insights. Summary of lab and HR-survey evidence on leisure-time bonuses improving on-the-job focus.

International Labour Organization (2023). Working Time and Work-Life Balance Around the World. Global review of working-time arrangements and productivity/health implications.

JAMA Network Open (Li, LZ., et al.) (2024). “Nurse Burnout and Patient Safety, Satisfaction, and Quality of Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Links burnout to higher error rates and lower quality and satisfaction.

McKinsey Global Institute (2023). The Economic Potential of Generative AI: The Next Productivity Frontier. Estimates that current AI could automate activities consuming 60–70% of time in many knowledge workflows.

OECD (2023). Employment Outlook 2023. Reviews early labor-market effects of AI; highlights limited job losses to date and uneven exposure.

OECD (2024/2025). Education at a Glance / TALIS 2024. Evidence on teacher shortages and classroom complexity; 73% average report of academically diverse classes.

VoxEU/CEPR (Gunnesmo & Hansen) (2025). “Lessons from Denmark’s eight-hour workday reform.” Historical analysis: 1% hour cuts raised hourly wages ~0.4% in Copenhagen, but weekly earnings fell; employment rose.

World Economic Forum (2023). “UK four-day work week: The results so far.” Summary noting 65% reduction in sick days and 71% lower burnout among participants.

World Health Organization & ILO (2021). “Long working hours increasing deaths from heart disease and stroke.” Estimates 745,000 annual deaths attributable to ≥55-hour weeks, underscoring health risks from chronic overwork.

Comment