African Venture Capital: Why Japan’s Equity Play Beats Debt-Heavy Models

Input

Modified

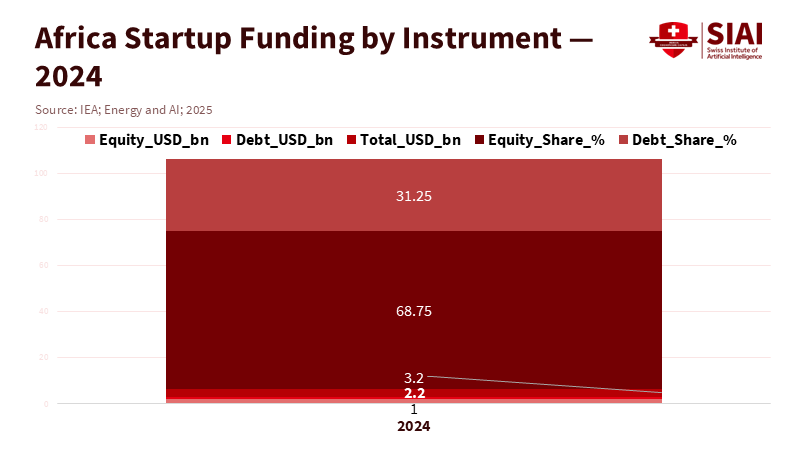

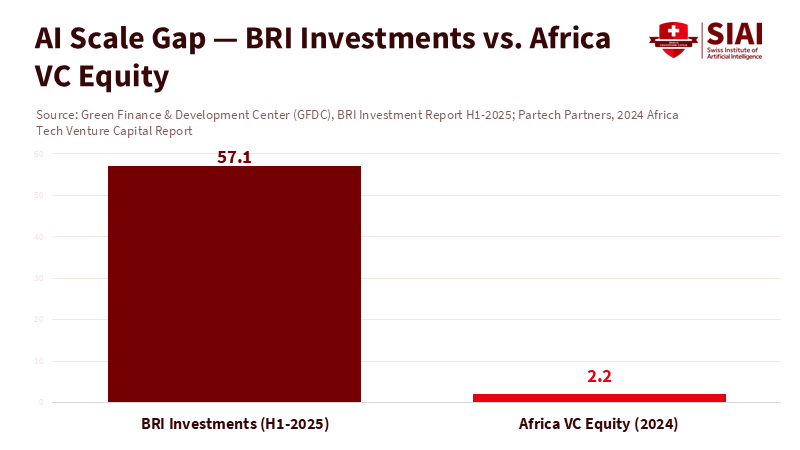

Japan’s equity play in African venture capital builds firms and skills The gap is stark: $57.1B BRI (H1-2025) vs $2.2B Africa VC equity (2024), with 31% still debt Link universities, co-investment rules, and procurement to crowd in patient equity and scale export-ready startups

A single comparison shows the choice before us. In the first half of 2025, Chinese firms invested about US$57.1 billion in Belt and Road projects, much of it in large, capital-heavy ventures led by major corporations. In all of 2024, African venture capital equity totaled US$2.2 billion, with another US$1.0 billion in debt. Equity was a mere rounding error compared to the scale of these big projects. The lesson is not that Africa needs to chase size. It is that influence follows the funding model. Equity that supports founders builds local companies, skills, and export capacity.

In contrast, debt that builds assets risks creating balance-sheet pressure without developing new capabilities. Japan’s recent push into African venture capital—small investments, founder-focused, and linked to talent pipelines—offers a more innovative alternative to debt-heavy models. The choice is clear: invest in people and firms now, or pay for stranded assets later.

African venture capital after the aid era

The last funding cycle highlighted the structural gap. In 2024, total startup funding in Africa reached US$3.2 billion, with about 31% of that in debt, a share that has risen as founders seek runway amid high interest rates. Equity remained at US$2.2 billion, roughly constant year over year, with fintech again driving much of the growth. This is not a failure of ambition; it signals issues regarding the cost of capital, currency risk, and a lack of suitable early-stage investors willing to work with teams through product-market fit. It also highlights that when debt fills an equity gap, repayment schedules often hinder growth. For systems that want jobs, exports, and tax bases, African venture capital needs more risk capital, not more loans. The data is precise; the policy path should be clear as well.

At the same time, the region is next to a giant with a different strategy. Chinese cross-border finance has shifted toward greater equity participation in select sectors. However, it still primarily focuses on significant corporate transactions and construction contracts in the energy and minerals industries. In the first half of 2025, BRI activities set records in oil, gas, mining, and green energy, led by companies such as East Hope, Xinfa, and LONGi. These deals build plants and pipelines; they do not typically seed local funds or incubators. This is a strategic choice, and a sensible one for a manufacturing export superpower. But for Africa’s startup ecosystems, the main issue is firm creation and growth, not just physical capital. African venture capital must be the lever.

From a long-term perspective, the concept is straightforward. Aid builds public goods. Megaproject finance builds assets. Venture capital builds firms. Those firms train engineers, product managers, and operators who then share expertise with the next group. The result is a compounding cycle of skills and entrepreneurship. In the 1990s, we learned this from Israel’s Yozma program; later, we saw similar efforts in Singapore and parts of Europe. Africa is ready for its own cycle, but it will only take off if early-stage equity is abundant and long-term. That is where Japan has begun to offer a different and more fitting approach to the needs of African venture capital today.

Why Japan’s equity model fits African venture capital

Japan has a large capital base and a still-small venture pipeline relative to its economy. Households hold about ¥2,200 trillion in financial assets, of which over half are in cash and deposits. Policymakers are encouraging that savings flow into productive risk through NISA reforms and calls to boost allocations to private assets. Yet Japan’s venture capital as a share of GDP remains below the OECD average. The result is a home market with abundant savings and limited capacity to absorb them at the early stage. Redirecting a slice of that savings into African venture capital is not charity. It is a way to pursue returns, diversify, and build alliances in the world's fastest-growing talent pool.

That idea is now becoming evident. In August and September 2025, Uncovered Fund and Monex Ventures launched a US$20 million fund for early-stage startups across Africa and MENA, with checks up to US$2 million in finance, mobility, logistics, and sustainability. Earlier, Verod-Kepple closed a US$60 million growth-stage fund with Japanese partners. At the same time, Samurai Incubate Africa continued supporting seed-stage teams across the continent. These are small amounts in global terms, but they have the correct format: founder-focused equity that aligns with Africa’s stage distribution and aims to spur spillovers into supply chains and skills. This is precisely the type of capital that most African ecosystems lack, which local universities and incubators can connect with.

Japan’s public tools amplify the private effort. JICA’s ABE Initiative moves African graduates through Japanese universities and internships, developing bilingual, bicultural managers who can lead joint ventures and product teams. Project NINJA collaborates with startup hubs in over twenty African countries to connect local founders with Japanese firms and investors. This combination—student pipelines, corporate partnerships, and risk equity—turns “development cooperation” into a market-building engine. It places African venture capital within a talent system rather than a deal flow silo. Policymakers should note the sequence: train people, connect firms, then invest.

A domestic shift in Japan adds momentum. Lawmakers have urged the GPIF and other large institutions to increase allocations to private equity and venture capital. Corporate reforms and a mild inflation environment are encouraging cash to move off balance sheets and into risk. Large VC formations in 2025 indicate deeper pools of capital seeking deployment. Some of that can be directed, via specialized funds and co-investment platforms, to African venture capital in sectors where Japanese firms excel: climate tech, mobility, manufacturing tech, and digital infrastructure. The fit is industrial, not superficial.

Execution: how schools and ministries can make African venture capital work

The education system is the pivot. Venture capital flows matter only if there is talent ready to take on those opportunities. University leaders should design degree-plus-studio programs that combine applied labs with investor-backed milestones. The World Bank’s ACE programs demonstrate how center-of-excellence models can boost accreditation, research output, and industry links in West, East, and Southern Africa. Linking those centers to African venture capital funds that can offer pre-seed funding against lab-tested prototypes tightens the pipeline. Students become founders, interns become operators, and capstone projects become companies. This is not just a theory; it is a policy choice to blend funding with education.

Ministries can accelerate progress with three straightforward actions. First, allow public research grants to convert to equity based on clear triggers, ensuring that state money isn't a dead end when a student team finds product-market fit. Second, create procurement sandboxes that enable initial customers for local startups in health, education, logistics, and climate services. Third, publish a simple co-investment rule: for every dollar of foreign early-stage equity in designated sectors, the public sector invests cents on the dollar on the same terms. This aligns with OECD guidance on government venture capital: invest where markets are weak, attract private funding, and avoid heavy involvement. If done correctly, African venture capital can serve as both a training and a financing tool.

Teacher colleges and technical universities should adapt to teach venture-related skills. Short courses in product design, data tools, and compliance can enhance existing curricula. Japanese partners can contribute here, as their strengths include lean manufacturing, kaizen methods, and supplier development. JICA’s programs already promote kaizen among thousands of firms; adjusting that for startups is simple. The goal is not to mimic Silicon Valley. It is to create operators who can deliver reliable products to African markets at African price points. This is how African venture capital turns funding into jobs.

Finally, connect the exchange loop. ABE alumni should be placed in venture-backed companies at home as CFOs, operations heads, or compliance leads; the diaspora network should be treated as a talent pool, not just a source of remittances. Japan can embed technical advisors in African accelerators for one- or two-year assignments, with matched placements for African mentors in Japan’s startup hubs. The result is a mutual skills market connected to African venture capital. Finance is the spark, but skills are the flame.

Answering the critics of African venture capital

Skeptics raise three points. First, they argue exits are rare, leading to disappointing early-stage returns. Second, they claim that foreign VCs will concentrate in “Big Four” markets, neglecting the rest. Third, they suggest that a Japanese push is merely soft power in a different guise. Each argument has merit; none is insurmountable.

Regarding exits, the solution is to build scale in sectors that already have buyers, such as payments, distributed energy, and logistics tech, and link startups to regional acquirers, not just global ones. As shown by the 2024 funding data, fintech attracted the largest share of equity and major deals, where early liquidity is most likely to occur. Debt’s 31% share suggests that revenue-backed models exist; converting the best of those into equity stories will lead to exits. This is a viable path for African venture capital, not just a hope.

Regarding concentration risk, policy can help shift investor behavior. The Partech report’s stability hides significant differences among ecosystems. Still, procurement sandboxes and transparent co-investment can extend risk into secondary cities and new sectors. Japanese funds are already showing diversity: small amounts at the seed stage, US$2 million at the early growth stage, and regional funds like Verod-Kepple at Series A/B. That range is crucial because Africa’s deal flow is heavy at the seed stage and thin at later stages. With the right co-investors, African venture capital can ease that drop-off. This is how you keep founders in-market rather than forcing them to relocate to access capital.

The soft-power critique requires a clear response. Yes, strategy is involved. But the means influence the outcomes. BRI-style engagement in the first half of 2025 reached record highs. It relied on significant corporate resources in the energy and mining sectors. That builds assets and leverage. The Japanese approach—which combines human-capital pipelines with early-stage equity—builds firms and skills. Both strategies transform the landscape; only one leaves behind founder cohorts capable of hiring, training, and exporting. Suppose the aim is resilient partners, not just projects. In that case, African venture capital supported by Japanese equity is the more effective instrument. The data on who leads BRI deals—and where equity versus construction dominates—highlights the difference.

Move fast on equity, measure impact through people

Return to the scale gap we began with: US$57.1 billion in Chinese BRI investments in just six months versus US$2.2 billion in African venture capital equity for an entire year. That gap will not close with speeches. It will close when ministries tie procurement to purchasing from startups, when universities connect labs with pre-seed funding, when public investors contribute patient capital, and when Japanese partners continue what they have started—investing in founder-first equity and training the managers who can help it succeed. We should measure success properly: by the number of local firms reaching product-market fit, by the engineers they hire, and by the export revenues those firms generate. If we follow that approach, others will adopt this model, just as skeptics once followed Israel’s or Singapore’s. The more innovative course is clear. It is time to make African venture capital—and the people who drive it—central to our strategy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

African Private Equity News. (2025, Aug. 28). Japanese venture firms set up $20m fund for African startups.

Ecofin Agency. (2025, Aug. 25). Two Japanese venture capital players create a fund for African startups.

Green Finance & Development Center (Nedopil). (2025, July 17). China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) investment report 2025 H1.

JICA. (n.d.). Master’s Degree and Internship Program of African Business Education (ABE) Initiative.

JICA. (2025, July 25). Project NINJA overview (English).

JIC (Japan Investment Corporation). (2025, July 31). Investment Activities & Policy presentation.

OECD. (2025, Apr.). Understanding Government Venture Capital.

OECD. (2024, Aug.). Measuring progress towards inclusive and sustainable growth in Japan.

Partech Partners. (2025, Jan. 23). 2024 Africa Tech Venture Capital Report.

Reuters. (2025, Jan. 31). BOJ expects rising inflation to spur demand for new financial services (household assets data).

Reuters. (2025, Apr. 23). Japan lawmakers urge pension fund to invest in domestic private equity and VC.

Samurai Incubate Africa. (n.d.). Firm overview.

TechCrunch. (2024, Apr. 9). Verod-Kepple Africa Ventures closes first fund at $60m.

VCCircle. (2025, Aug. 28). Uncovered Monex Africa Investment Partnership (UMAIP) to invest in Africa and MENA.

Comment