The Quad's New Minerals Map: Why Rare Earth Supply Chain Resilience Depends on Central Asia and India's Re-use Edge

Input

Modified

Rare earth price spikes show fragile supply chains The U.S. extends the Quad into Central Asia to secure non-China mining and processing India’s recycling and magnet capacity—backed by education and procurement reforms—delivers near-term resilience

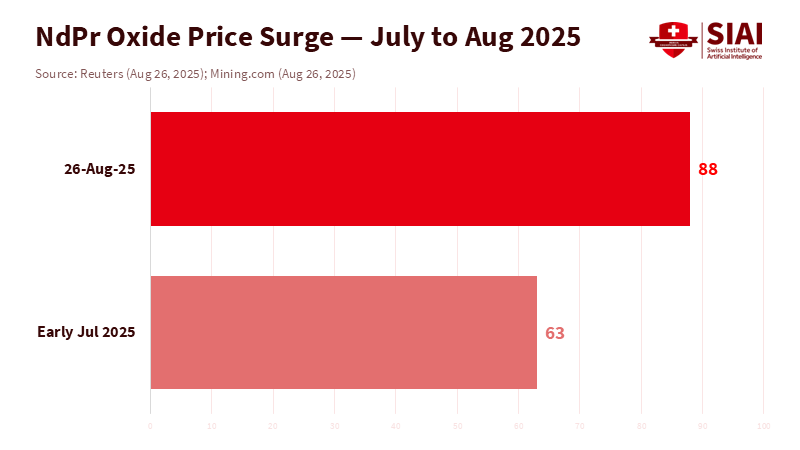

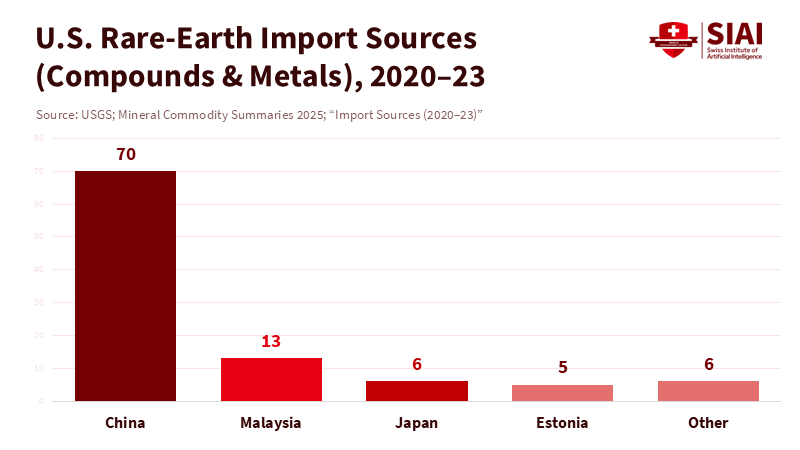

A single price change reveals the situation. In late August 2025, the price of neodymium-praseodymium oxide surged nearly 40 percent in just a few days, rising from about $63 to $88 per kilogram. This spike followed a U.S. miner's decision to cut shipments to China as part of a push for domestic refining. The sudden rise highlighted the limited buffer stocks and the ongoing concentration of processing. It also underscored why rare earth supply chain resilience is now a key test for industrial policy. China still manages most of the separation and processing, and it tightened controls this year. In 2024, the United States still drew the majority of its imports from China. Any change in one link causes prices to fluctuate. If Washington is committed to strategic independence, it must combine new mines with allies and rapidly convert scrap into feedstock. This is where the extended Quad and India's urban mining capacity become crucial.

Rare Earth Supply Chain Resilience and the Price of Time

Strategy meets urgency. Global mine output increased in 2023, but processing remained concentrated, and market shocks kept occurring. China's export volumes rose in 2024 even as prices dropped, only to reverse due to policy changes and supply issues. This is not a typical commodity cycle; it is an industrial system experiencing pressure. The United States responded by investing in domestic separation facilities—from the Lynas heavy rare earths plant in Texas to new oxide projects supported by the Defense Department—aimed at reducing reliance on China. The goal is not just security; it is to maintain price stability over time. Until separation capacity expands in allied markets, every disruption will impact magnets, motors, and defense systems.

The immediate risk is evident. China implemented stricter rare-earth regulations this year, including stricter quotas and greater central control. This new measure, along with earlier licensing actions, adds policy uncertainty to a market already affected by bottlenecks in Myanmar and seasonal fluctuations in Chinese manufacturing. If Washington and its partners depend on ad hoc purchases and small stockpiles, they will be reactive rather than proactive. Achieving rare earth supply chain resilience requires a diverse approach: various mines, midstream separation outside China, and a growing supply of recycled feedstock. Because new mines take years to develop, the quickest solution from 2026 to 2028 is not extraction, but instead processing and re-use.

An Extended Quad Meets Central Asia

The geography of the Quad is evolving, even if the name remains the same. Recently, the United States hosted five Central Asian leaders in Washington, placing critical minerals at the forefront of discussions. Kazakhstan subsequently signed a memorandum of understanding with the U.S. to cooperate on minerals. This is not just branding; it is a supply strategy. Central Asia has significant potential for rare earths and other metals and lies between Russia and China. For the United States and its Indo-Pacific partners, engaging this region reduces the risks associated with single supply routes. It opens opportunities for midstream projects that supply allied processors. Together with the U.S.-led Minerals Security Partnership, the message is clear: build a broader upstream and midstream network quickly.

Europe is already advancing. The EU's partnership with Kazakhstan is shifting from political agreements to actual projects, in line with its Critical Raw Materials Act, which sets targets for extraction, processing, and recycling by 2030. These benchmarks are crucial for the broader Quad objectives. They quantify "resilience" in concrete terms and limit over-reliance on any one nation. If the U.S. and its allies align their procurement with these standards—40 percent processing in domestic markets, 25 percent from recycling, and limitations on dependence on a single country—they can create strong demand signals that will finance separation and oxide plants from Texas to Tamil Nadu. Working with Brussels could turn Central Asian bilateral agreements into viable projects.

There will be challenges. Detractors will argue that Central Asia lacks capital, is landlocked, and has complex politics. All of this is true. However, ore will move to where separation facilities exist. Ports in the Gulf and the Black Sea are already natural exits for Kazakh metals, and project financing can be arranged through agreements with allied processors in the U.S., Japan, and Australia. The key is to combine mine development with offtake that supports new separation capacity. This approach will transform memoranda into tangible results.

India's Moment in Re-use

Re-use is an overlooked but decisive factor in rare earth supply chain resilience. Currently, less than 1% of rare earth magnets come from recycled sources, even though technologies—such as hydrogen decrepitation, specialized hydromet, and direct "magnet-to-magnet" methods—are well developed. Additionally, the world faces a growing wave of e-waste with low recycling rates. India is ideally positioned to address this challenge. It has a large electronics market, a robust repair and refurbishment ecosystem, and new regulations promoting extended producer responsibility with clear annual targets. If policy directs this ecosystem toward magnet recovery, India could supply a growing share of neodymium-praseodymium units from urban mines at costs lower than virgin oxide in tight markets.

New incentives support this direction. New Delhi has begun to promote domestic NdFeB magnet manufacturing through targeted schemes and expanded production-linked support. It has also increased the role of state-owned IREL in upstream processing while encouraging private investment in midstream operations that convert imported or domestic concentrates into separated oxides. These initiatives do not aim to replace mines in Australia or the U.S.; they focus on ensuring that when prices surge, a parallel supply of magnets and oxides can emerge from scrap and end-of-life products. This approach keeps India strategically distanced from China while avoiding a stark choice between cost and security.

However, reality poses challenges. Most of India's e-waste is handled through informal channels, with low recovery efficiency and significant health risks. While formal capacity is growing state by state, it needs to scale up and adopt standards. The solution is straightforward: use EPR credits to incentivize high-yield magnet recovery; mandate designs that allow easy magnet removal; and direct public procurement to products containing verified recycled rare-earth materials. India's strengths lie in organization and cost, not just technology. By channeling its refurbishment networks into certified magnet recovery operations and linking them with domestic or allied separators, India can lead the Quad in re-use within three years.

What Educators and Systems Must Do Now

Education policy plays a vital role; it is crucial. Universities and polytechnics should develop one-year micro-programs focused on magnet design, separation chemistry, and recycling operations, emphasizing plant safety and environmental controls. Engineering schools should create testbeds where students can disassemble motors, extract magnets, and operate small-scale decrepitation units under supervision. Business schools can offer "materials markets" labs that simulate offtake contracts and hedging strategies, preparing graduates to assess risk as real-world supply dynamics change. These initiatives will produce a workforce ready for separator plants and recycling facilities from day one. They will also lessen the training demands on companies that need to act quickly in 2026 and 2027.

Systems must also improve their purchasing practices. Public buyers, from school districts to defense agencies, should draft contracts requiring a minimum recycled rare-earth content by 2028, gradually increasing it to 2030, in line with the EU's recycling targets. This will create stable demand for urban-mined feedstock across the Quad and its partners. Education ministries should provide standard teardown guides for the motors and devices they procure, including barcodes that help recyclers identify where the magnets are located and how to extract them safely. None of this work is glamorous, but it enhances the resilience of the rare-earth supply chain. It transitions graduates into skilled operators and procurement into effective policy.

The final step is to align strategies across borders. The United States can focus on midstream separation. Australia and Japan can supply and refine materials. India can take the lead in re-use and large-scale magnet assembly. Central Asia can broaden the upstream supply and secure long-term contracts. Europe can provide regulatory standards and increased demand certainty. The necessary pieces are already in place: Defense Production Act funding for separation capacity; new U.S. oxide targets; EU regulations limiting dependence on a single country; and fresh agreements that bring Kazakhstan and other nations into the strategy. Education policy should reflect this roadmap. Create exchange programs that emphasize plant internships rather than classroom instruction alone. Share safety protocols, process control curricula, and procurement templates across the network. Transform the Quad's minerals initiative into a talent initiative as well.

The price spike in August was not coincidental; it served as a warning. A rare-earth market reliant on a single dominant processor will continue to disrupt downstream sectors. The solution is to effectively address rare earth supply chain resilience in three areas at once: integrate Central Asia into the supplier network; establish allied separation and oxide capacity; and leverage India's re-use capabilities so that scrap serves as a second mine. If the United States aims for autonomy without suffering from price volatility, this is the only viable approach. It can circumvent superficial negotiations that overlook risk and instead build a sustainable system that can withstand pressure. The responsibilities are clear for every player in the supply chain—educators, administrators, and policymakers alike. Prepare individuals for the facilities we are developing. Buy in ways that promote recycling. Fund projects where ore meets demand. By doing this, the next price shock will be a ripple rather than a rupture.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2025, September). What to know about China's new regulations on rare earths. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

Anadolu Agency. (2025, November 6). Kazakhstan and the U.S. sign memorandum on cooperation in critical minerals. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

Business Defense / DoD. (2022, June 14). DoD Awards Key Contract for Domestic Heavy Rare Earth Separation Capability. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

East Asia Forum. (2025, November 7). The Quad digs deep for critical mineral supply chain resilience. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

European Commission. (2024–2025). Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) pages. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

Global E-waste Monitor. (2024). The Global E-waste Monitor 2024. UNU/ITU/UNITAR. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

IREL (India) Ltd. (2025). Annual Reports portal. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

Lynas Rare Earths. (2023, August 1). U.S. DoD strengthens support for Lynas U.S. facility. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

Minerals Security Partnership (U.S. State Department). (n.d.). Overview. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

Reuters. (2025, January 13). China's rare earth exports in 2024 climb as home demand limited. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

Reuters. (2025, August 26). Rare earth prices hit two-year peak after MP Materials stops China shipments. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

Reuters. (2025, November 6). Trump meets Central Asian leaders to boost critical mineral ties. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

U.S. Geological Survey. (2024). Mineral Commodity Summaries: Rare Earths 2024. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

U.S. Geological Survey. (2025). Mineral Commodity Summaries: Rare Earths 2025. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

The Australian / Live coverage. (2025, July). Rubio pushes for stronger critical mineral supply chain at Quad. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

The Central Pollution Control Board (India). (2024, January 23). FAQ under E-Waste (Management) Rules, 2022. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

The European External Action Service. (2025, April 4). EU and Kazakhstan take the next step in their cooperation on critical raw materials. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

The Times of India. (2025, October). India's rare earth boost: Govt approves ₹7,300 crore scheme; aim to diversify away from China. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

The Times of India. (2025, October). 95% of Delhi's e-junk still being handled informally. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

The Economic Times. (2025, August). India plans ₹1,345 crore rare earth magnet incentive scheme. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

U.S. State Department (archival page). (2021–2025). Minerals Security Partnership. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

White House / AP News. (2025, November 6). Trump hosts Central Asian leaders as U.S. seeks to get around China on rare earth metals. Retrieved November 7, 2025.

Comment