Export Specialization Strategy and the New Logic of Free Trade Agreements

Input

Modified

FTAs expand exports without hollowing local markets Regional deals boost affiliate-to-third-country sales while domestic supply shifts to higher-value stages Policy should anchor high-skill functions at home and train compliance and data roles to use FTAs well

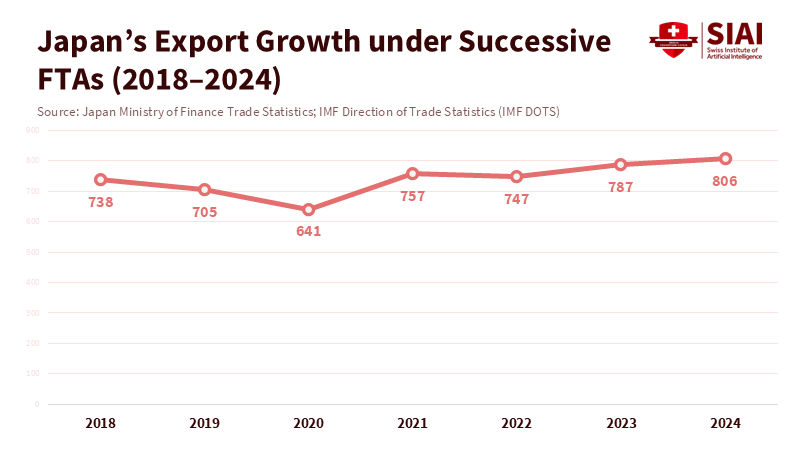

One statistic should end the misleading notion that free trade agreements harm local industry. As of 1 September 2025, the World Trade Organization recognizes 375 active free trade agreements worldwide. Governments continue to sign these agreements because companies are finding them useful. A clear example is Japanese multinationals. Their export specialization strategy, which focuses on a few key products or industries for export under these agreements, has increased sales to third countries. In contrast, local sales in host markets have remained steady. Recent analysis of Japanese manufacturers' overseas affiliates shows that regional trade agreements and huge multi-country deals boost exports to outside markets without consistently hurting local sales where they operate. In other words, export growth does not depend on weakening domestic demand; it depends on coordination. This insight is essential now because most public debates still view export specialization strategy as a zero-sum game. The data suggests it can be a tool for stability.

How Free Trade Agreements Reshape Export Specialization Strategy

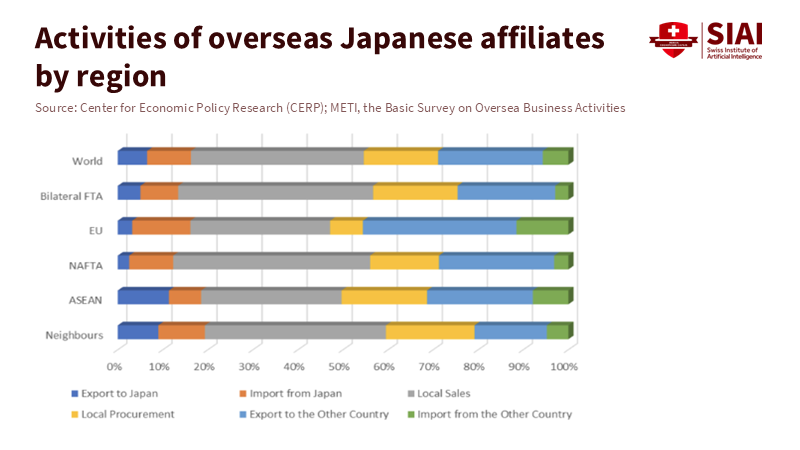

The common belief is straightforward. A Free Trade Agreement (FTA) leads to lower import prices. Strong exporters increase shipments abroad and reduce supply in the home market. Plants shut down, workers lose bargaining strength, and communities deteriorate. This idea sounds logical, and it can be politically advantageous, but the evidence does not support it. Studies of Japanese manufacturing groups reveal a different story. Bilateral FTAs do not have a clear or systematic effect on local sales by overseas affiliates.

In contrast, regional FTAs have a substantial positive impact on exports from those affiliates to third countries. This means firms leverage extensive, multi-party deals to access more buyers, and domestic supply to local markets does not collapse in the process; it shifts and becomes more specialized. This is how the export specialization strategy operates in reality.

This pattern shows that the export specialization strategy is proactive rather than exploitative. Japanese firms break production into stages, placing each stage where skills, logistics, and tariff rules are optimal. The result is a dense supply chain map spanning multiple FTA regions rather than a simple distinction between home and abroad. Research on Japan's trade profile indicates that even as of 2020, Japan maintained a clear comparative advantage in 24 complex, high-value product categories, including transport equipment and precision machinery. These products accounted for nearly 90 percent of Japan's total exports and ranked high globally. This information tells us that specialization does not equate to vulnerability. Instead, it reflects a strategic focus on complex niches where competitors struggle to match quality.

Export specialization strategy under modern FTAs is not about moving operations and forgetting. It involves orchestration. The lead firm uses tariff cuts, common technical standards, and digital trade chapters to manage flows of parts, services, and data. These flows support both export growth and a stable local supply. The host economy benefits from jobs in compliance, logistics, and advanced manufacturing. The home economy experiences increased volume in its strongest sectors. The alarming idea that "exports will hollow us out" overlooks this point. The harm does not stem from exporting itself; it arises from a failure to understand who does what, where, and under which agreement. A country that grasps this framework can leverage its strengths.

Japan's Supply Chain Strategy Is Not Protectionism; It's Precision

Why is Japan significant? Because it participates in several major agreements simultaneously, it treats each as a resource. Japan is a party to the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement, which has been in effect since 2019. The European Union already exports around €70 billion in goods and €28 billion in services to Japan each year. This deal eliminates tariffs on cars, electronics, and other industrial products. It also addresses non-tariff barriers such as product standards and public procurement rules, which are as crucial for complex manufacturing as tariffs. On 28 October 2023, the EU and Japan also reached an agreement on cross-border data flows, incorporating digital access into the same framework. This means the deal involves not just physical goods but also design files, testing data, and compliance records crossing borders with minimal friction.

Japan is also part of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. It has a digital trade agreement with the United States that safeguards cross-border data transfer, limits forced data localization, and provides legal protection for encrypted communications. The U.S.–Japan framework also lowers tariffs on billions of dollars of U.S. agricultural exports and key industrial inputs, reducing production costs for Japanese manufacturers and promoting more stable sourcing. These arrangements are not merely tariff exchanges; they function as operating systems. They allow a firm to manage design in one country, software and regulatory compliance in another, and large-scale assembly in yet another, without encountering obstacles when shipments cross borders.

Firms then route production through the agreement that offers the best mix of tariff relief, regulatory certainty, and market access. Recent analysis of overseas affiliates shows that regional FTAs, particularly those covering large markets such as ASEAN, the European Union, North America, and China, boost affiliates' exports to external buyers. Local sales in the host country did not decline consistently. In brief, the precise use of overlapping agreements promotes an export specialization strategy without necessitating a retreat from local customers. This is why discussions of "protectionism" miss the mark. Japan is not isolating its industries; it is positioning each high-value activity within the most supportive regulatory framework.

Why 'Hollowing Out' Fears Overlook Domestic Adjustment Capacity

There is a persistent fear that when a country adopts an export specialization strategy, domestic suppliers will be driven out because they cannot compete on price once tariffs decrease. This fear is real and easily exploited in public discussions. However, it is often misplaced. The Japanese experience shows that firms did not respond to broader FTAs by closing domestic operations. Instead, they reorganized their activities. High-skill, high-margin processes remain close to core engineering teams, while lower-margin, labor-intensive processes are relocated to affiliate sites within favorable FTA zones. This is not an exodus; it is a redistribution. It views production as a network rather than a single facility.

This behavior has implications for labor markets. Adjustment resembles role changes more than mass layoffs. Work shifts toward compliance with rules of origin, digital documentation, sustainable sourcing audits, and quality control for complex materials. These roles require higher skills and often come with better pay. They also help retain production domestically, as oversight functions are tied to design. When we hear that an FTA will "move all our jobs overseas," we should ask more precise questions. Which jobs are affected? At what stage of the production chain? Under which agreement? The answer usually reveals that the so-called "lost" jobs are in low-margin tasks that can be done anywhere, while the more valuable jobs remain local.

Critics may argue that Japan is different. They might claim that such precise coordination relies on a cultural commitment to process discipline that is hard to replicate. There is some truth to this. Japan's export base largely centers on complex manufacturing, where it has been a leader globally for decades, and it still shows clear advantages across 24 high-complexity product categories. However, we should be cautious before labeling this as unique. The structure of the agreements is as essential as company culture. The EU-Japan agreement reduces tariffs, aligns standards, and now protects cross-border data flows. The U.S.–Japan Trade Agreement and the U.S.–Japan Digital Trade Agreement minimize friction for goods and data. These institutional choices make coordination quicker and cheaper. Other countries can and are signing similar agreements.

Policy Priorities for the Next Wave of Regional FTAs

We face a clear policy challenge. Should we view export specialization strategy as a threat to local supply or as a tool to enhance local strengths? The evidence suggests we should choose the latter. This requires a new understanding of "keeping industry at home" and a redefined role for education and procurement. Industrial policy must stop treating every factory job as the same. Jobs connected to high-margin design, quality control, compliance, and complex assembly are strategic, whereas jobs tied to simple, low-margin tasks are inherently mobile. Trying to keep the entire chain in one place wastes resources and fails. Supporting firms in securing the strategic stages while allowing other stages to operate in partner markets covered by extensive FTAs keeps the ecosystem healthy. Evidence from Japanese affiliates shows that this model increases exports without harming local sales.

Education policy must evolve alongside trade policy. Technical colleges, vocational schools, and business programs should prepare students to conduct rules-of-origin audits, manage cross-border data compliance, and coordinate multi-location production strategies. The recent EU-Japan agreement on cross-border data flows demonstrates that data management is now integral to market access, not an afterthought. Export paperwork has moved beyond a clerical task; it has become strategic infrastructure. To ensure firms retain high-value functions at home, we need to train people who can manage those processes, certify their outputs, and demonstrate to customs officers and data regulators that they comply with all rules.

Regional FTAs should be assessed by their breadth, not just by how deeply they cut tariffs. The WTO now reports 375 active agreements. Many of the most impactful ones cover a wide range of topics, including investment regulations, procurement access, technical standards, and digital trade. These features create stable platforms for complex production networks and enable a firm to serve domestic customers while exporting on a larger scale. Policymakers who frame FTAs as "cheap imports versus closing factories" are fighting the previous battle. The real challenge is to shape these agreements to keep high-value processes anchored while allowing low-value tasks to adapt in ways that support them.

The existence of 375 active free trade agreements indicates that trade politics have progressed. We are no longer in a scenario where a single bilateral deal devastates the domestic industry. We are in an environment where interconnected regional agreements support export specialization strategies. Japanese manufacturers demonstrate how this framework operates. Regional FTAs boost exports from affiliates to third markets, while bilateral FTAs do not drastically reduce local sales. Domestic demand does not disappear; it shifts toward higher-value processes that are difficult to replicate. This is not a unique achievement that only Japan can attain; it is a deliberate practice. It involves the thoughtful use of tariff reductions, shared standards, and cross-border data regulations to protect the crucial parts of the supply chain. The policy decision is straightforward: we can treat FTAs as a threat and continue losing ground, or we can adopt them as tools of industrial policy and educate firms, students, and regulators on how to use them effectively.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

European Commission. (2024). EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement and cross-border data flows, and EU export and services figures to Japan.

Kato, A., & Nishiyama, H. (2025). Supply chains and free trade agreements: Effects of FTAs on overseas affiliates of Japanese manufacturing multinationals, and the role of regional FTAs in driving exports to third countries; WTO count of 375 FTAs as of 1 September 2025.

Podoba, Z. S., Gorshkov, V. A., & Ozerova, A. A. (2021). Japan's export specialization in 2000–2020: Revealed comparative advantage in 24 high value product groups covering about 90 percent of national exports.

U.S. Department of Commerce. (2024). Japan – Trade Agreements: U.S.–Japan Trade Agreement and Digital Trade Agreement, tariff cuts on billions of dollars of U.S. agricultural exports and protections for cross-border data.

Comment