ExpoFree Trade Mega Bloc, Not Tariff Walls: A Realistic Map for Education and Growth

Input

Modified

Trade barriers worth $2.3T are rising and choking education trade A free trade mega bloc can keep people, data, and ideas moving Prioritize shared visas, interoperable credentials, and protected cross-border data

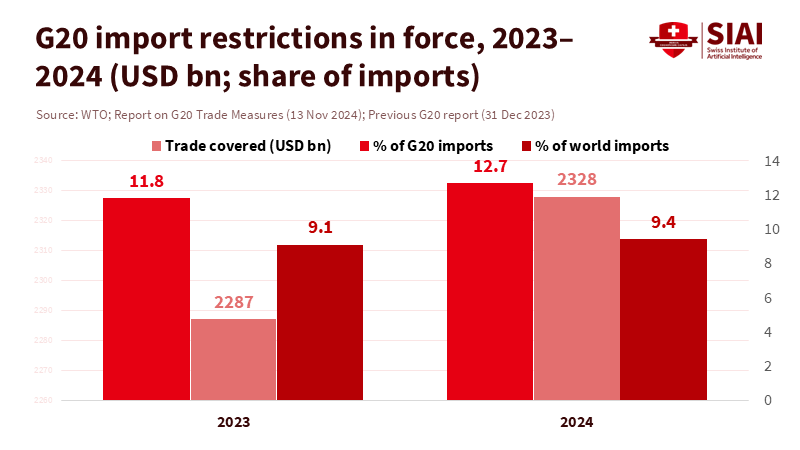

One number underscores the urgency of the situation: US$2.3 trillion. This is the value of G20 import restrictions in force in 2024, accounting for 12.7% of G20 imports and 9.4% of world imports, as per the WTO. When such a significant portion of trade encounters new barriers, the impact is felt first in classrooms, labs, and ed-tech firms. Costs escalate, mobility diminishes, and collaboration slows. The multilateral referee remains inactive, and tariff politics are back in vogue. In this scenario, the most pragmatic approach is not to yearn for a return to the past. It is the arduous task of constructing a free trade mega bloc—an open, rules-based “bloc of blocs” that facilitates the movement of services, data, ideas, and students, even as the global rulebook recuperates slowly. The choice is stark: either rally for openness or witness fragmentation erode the future of learning.

Why a Free Trade Mega Bloc Beats a Tariff War

The dispute system that used to keep everyone honest remains blocked. The WTO’s Appellate Body cannot hear appeals; this vacuum encourages unilateral actions and retaliatory measures. It also undermines the credibility of the rules that schools, universities, and ed-tech exporters rely on when they sell services across borders or face sudden restrictions. In the context of a free trade mega bloc, the WTO plays a crucial role in setting and enforcing rules that ensure market access, standards, and data flows. A free trade mega bloc provides a safeguard: when global enforcement weakens, strong regional rules can ensure market access, standards, and data flows.

The potential benefits of a free trade mega bloc are substantial. RCEP alone encompasses about 30% of world GDP and population and is now fully operational across East Asia and the Pacific. The EU single market is the most integrated project globally, and USMCA links North America’s value chains. CPTPP, now including the United Kingdom, serves as a platform for rules on services, investment, and digital trade. By amalgamating these legal structures—cooperation among equals, rather than erecting barriers—a free trade mega bloc can keep the pathways of twenty-first-century trade open. Simultaneously, we continue to mend multilateral systems.

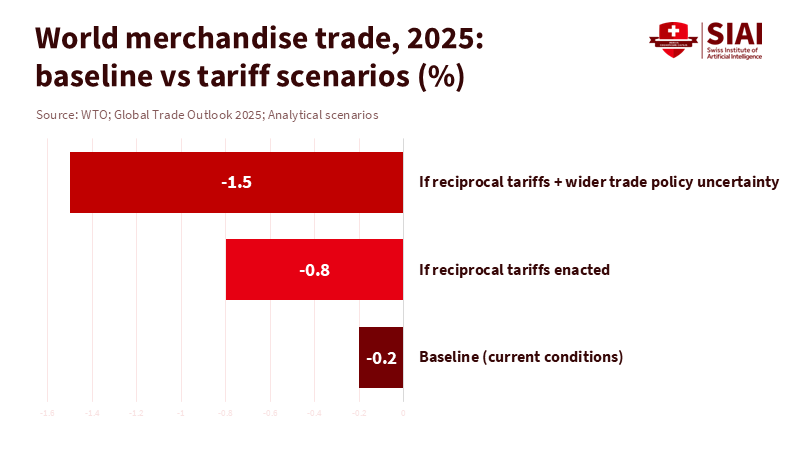

The alternative is evident. In 2025, Washington indicated broad “reciprocal” tariffs. It sought a 10% baseline on imports, moves that the WTO warned could reduce global merchandise trade by 1% that year. This might seem small, but it is not when your business model relies on student recruitment, cross-border credentialing, or cloud-hosted learning platforms. The IMF’s findings on fragmentation show that long-term output losses can be much greater, averaging several percentage points of global GDP, as supply chains and knowledge flows shift in costly ways. The lesson for education systems is straightforward: protecting against tariff shocks now is cheaper than rebuilding trust later.

Designing a Free Trade Mega Bloc for Education and Services

Education is traded, even if we avoid that term. Universities sell degrees and research capacity. School systems buy curricula, testing services, and ed-tech platforms. Students also represent a form of human-capital trade, and demand is rising. By 2024, there will be around 6.9 million international students, a record that supports entire ecosystems of providers and host cities. Digital delivery is even larger: digitally delivered services exports reached US$3.82 trillion in 2022, over half of all services trade, making education one of the fastest-growing segments. A free trade mega bloc must treat mobility and data as twin pillars—portable people and portable learning.

What does that look like in practice? First, align visa and recognition rules across blocs. This means mutual recognition of micro-credentials and quicker skills assessments within and between the EU, RCEP, CPTPP, USMCA, and AfCFTA. Eurostat data demonstrate the importance of scale: intra-EU goods trade is larger than extra-EU, and mobility frameworks like Erasmus capitalize on that depth. The same logic applies to services and education. The more predictable rules are within the mega bloc, the easier it becomes to maintain flows when global situations become challenging.

Second, establish digital guardrails. The EU-Singapore 2024 digital trade agreement illustrates how to ensure cross-border data flows while protecting consumers, using e-signatures, and setting limits on forced source-code transfers. This approach can be adopted across blocs and linked to create a compliant framework for ed-tech vendors. The WTO’s 2025 analysis connects growth in digitally deliverable services with increased cross-border AI knowledge spillovers. To encourage faster improvements in learning platforms, the free trade mega bloc should make seamless digital trade the standard—while protecting it from tariffs.

Third, inclusivity is key. The free trade mega bloc should not be exclusive but should include the Global South. AfCFTA is transitioning from theory to practice, with more members applying tariff preferences and establishing standard service protocols. Investments in energy, connectivity, and cloud regions follow scale. Suppose the mega bloc helps Africa connect to education and research networks with fast links and clear data rules. In that case, the benefits will extend well beyond tuition payments. The result is resilience: more partners, more connections, fewer vulnerabilities.

Risk Management: Avoiding a 1930s Bloc Trap

History gives us two models. The 1930s showed that rigid, exclusive blocs worsen economic shocks and escalate rivalries. The 1980s demonstrated that regional liberalization can act as a bridge to broader openness—creating stepping stones rather than walls. Today, we encounter both dynamics. The tone between the US and China sometimes resembles the 1930s. Meanwhile, RCEP and CPTPP across Asia and the Pacific reflect the 1980s: broad coverage, expanding membership, and rules that can be integrated. Our current task is to steer the system toward this second path intentionally.

That design must include escape routes. When tariffs increase in one primary market, demand often spikes in other markets or shifts forward in time. We witnessed this in 2025 as companies moved imports ahead of policy risks while AI hardware demand boosted trade volumes. Such volatility can disadvantage smaller education providers, who are unable to adapt. A free trade mega bloc can soften these swings by keeping alternative channels open for services and students, through rapid mutual recognition and compatible digital identities. The goal is to lessen the impact of the next shock on learning.

We also need an honest assessment of costs. The WTO’s monitoring shows restrictions stacking up rather than decreasing—fragmentation’s impact compounds. Policymakers should view every new non-tariff barrier, data localization rule, or arbitrary licensing requirement as a tax on the knowledge economy. The experience of intra-EU trade shows that robust internal rules help keep more trade flowing when the outside world becomes hostile. The same could apply within a free trade mega bloc—if its members commit to openness across services, investment, and the movement of people, and if they establish clear transparency and appeal processes. At the same time, the WTO’s overall system is being rebuilt.

A Practical Playbook for 2025–2028

For educators and university leaders, the action items are clear. Protect recruitment efforts by creating multi-market pipelines across connected blocs and building dual-delivery models that do not rely on a single visa policy. Use the mega-bloc strategy to diversify partner campuses and cloud regions. Please pay close attention to the new digital trade chapters; they will determine whether your platform can keep student data flowing, where you can store it, and how you certify its integrity across borders. Evidence suggests there is a real payoff: deeper digital trade correlates with faster diffusion of AI innovation, which leads to better learning tools.

For administrators and quality agencies, the next step is standards. Choose two or three credential frameworks and ensure they work together. Align learning outcome taxonomies—map skills to shared reference systems to enable automatic recognition across member economies. OECD and Eurostat data reveal that enrollment shares for international students have slowly increased over the last decade in many systems; this trend depends on speedy recognition and clear rules. A free trade mega bloc should be a place where speed and certainty thrive.

For ministers, the priority is to connect existing blocs rather than invent a new acronym. Begin with a joint protocol on student mobility that unites the EU, RCEP, CPTPP, USMCA, and AfCFTA around common standards: streamlined visas for accredited providers, reciprocal recognition for core micro-credentials, and an opt-in “safe harbor” for cross-border education data. Then implement a “fast lane” for appeals: if a provider faces an unexpected market barrier within the bloc, they would have a 60-day review window with interim relief. This approach is not a complete replacement for a reformed WTO, but it serves as a practical bridge. At the same time, Geneva rebuilds its two-tier dispute settlement.

US$2.3 trillion in accumulated import restrictions should catch everyone’s attention. It represents the cost of inaction. In a world where the referee cannot step in and tariff politics rise and fall with the news, we cannot leave the education sector exposed. The solution is not to romanticize the past or pick winners in a tariff battle. It is to build and connect what already works into a free trade mega bloc that favors openness by default, safeguards digital flows, and accelerates recognition of skills and studies. The depth of the EU, the scale of RCEP, the rules of CPTPP, the supply-chain integration of USMCA, and the potential of AfCFTA can create a path back to a multilateral order—without repeating the closed blocs of the 1930s. To expand access and productivity in classrooms, labs, and learning platforms rather than limit it, we must take action. Start with visas, data, and credentials. Secure them across blocs, and the education sector will manage the rest if we clear the way.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2025, October). WTO says AI-related buying binge and a spike in US imports spur unexpected rise in goods trade.

ASEAN Secretariat. (n.d.). Summary of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement.

Eurostat. (2025, May 7). Intra-EU trade in goods—main features.

Eurostat. (2024–2025). International trade in goods—An overview.

Eurostat. (n.d.). Learning mobility statistics.

International Monetary Fund. (2023, June). The costs of geoeconomic fragmentation. Finance & Development.

OECD. (2024, September). Education at a Glance 2024.

Politico. (2025, February 7). ‘Reciprocal’ tariffs on every country to be announced next week, Trump says.

Reuters. (2025, April 3). WTO says tariffs could bring contraction of 1% in global merchandise trade volumes.

Reuters. (2024, August 29; 2024, December 15). Britain says CPTPP agreement to come into force by December 15; Britain joins trans-Pacific pact.

WTO. (2024, November 13). Report on G20 Trade Measures (mid-Oct 2023 to mid-Oct 2024); News summary.

WTO. (2025, April 14). Global Trade Outlook 2025.

WTO. (2023, December 7). Digital Trade for Development.

WTO. (2025, September 17). World Trade Report 2025: Making trade and AI work together to the benefit of all (Executive Summary).

WTO. Appellate Body—Dispute settlement.

European Union & Singapore. (2024, July 25). EU and Singapore agree digital trade deal. Reuters.

Government of Singapore/ASEAN—AfCFTA updates and national implementation (South Africa DTIC). (2024–2025). AfCFTA implementation notes.

Migration Policy / WENR. (2025, August 22). International student mobility data sources: A primer.

(All sources accessed November 10, 2025.)

Comment