Continuity With Teeth: Why Takaichi's Japan Needs a Japan-India Education Corridor

Input

Modified

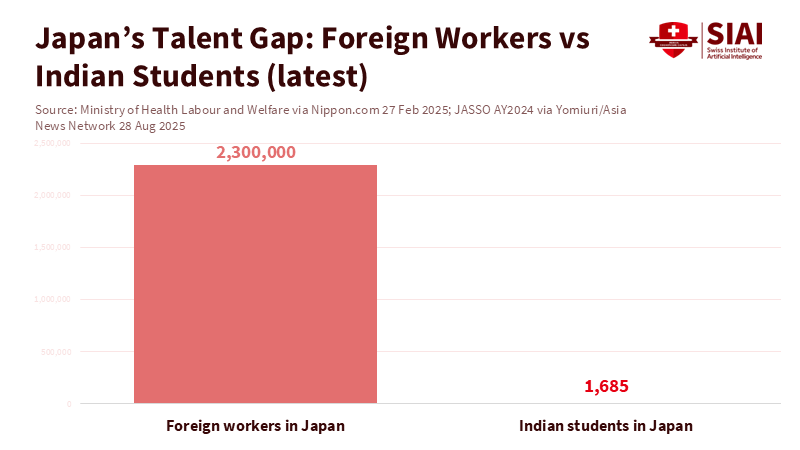

Japan’s labor is tight and the yen is weak Despite 2.3 million foreign workers, only 1,685 Indian students study in Japan A Japan–India education corridor would scale skills, lift productivity, and lock in a deeper partnership

Japan's labor market is tight, but the flow of skilled workers from India is minimal. As of October 2024, there were 2.3 million foreign workers in Japan. However, only 1,685 Indian students were enrolled there during the same academic year. This gap highlights a system driven by demand but restricted by limited paths for skills and education. A Japan-India education corridor—formal, scaled, and jointly funded—could connect Japan's need for talent with India's demographic advantage. It would transform random hiring and small scholarship programs into a strategic engine for growth, resilience, and regional stability. Japan's job-to-applicant ratio remains above one. Its currency is weak, prompting firms to move operations abroad and rush to modernize. These pressures are not theoretical; they directly impact productivity and wages. Filling the gap between workforce needs and student inflows—particularly from India—should be a top priority for Tokyo's new Indo-Pacific strategy.

The case for a Japan-India education corridor

Sanae Takaichi has taken office promising continuity: stronger security, closer alliances, and practical economic policies. A bilateral framework with India already backs this continuity. The Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement has been in place since 2011. In 2020, the defense forces signed a logistics agreement, and Quad coordination on health, technology, and infrastructure has developed into regular ministerial meetings. None of this requires starting from scratch. It needs focus: leverage trade, security access, and technology initiatives to create a Japan-India education corridor that efficiently moves individuals—students, apprentices, researchers, and qualified workers. This approach turns continuity into capacity and makes diplomacy a tangible source of skilled labor.

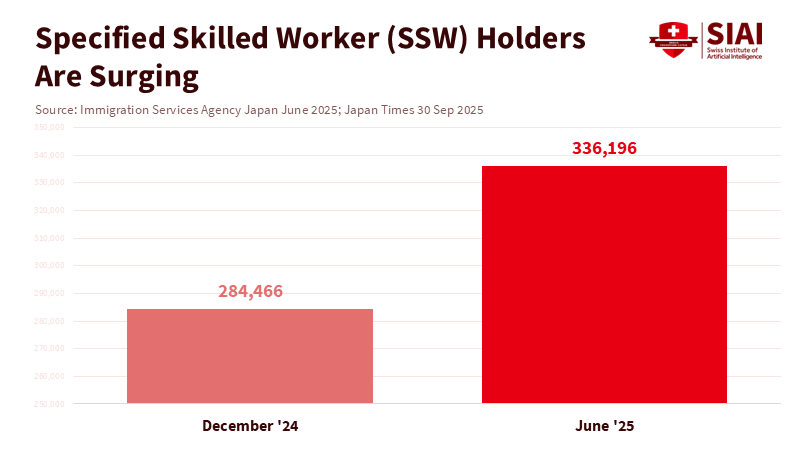

Japan's economic indicators make this case clearer. Since mid-2024, the yen has remained around ¥160 per dollar, despite significant intervention. A weaker currency helps exporters but increases import costs and reduces real incomes. Labor data shows a continued tight market: unemployment at 2.6% and a jobs-to-applicants ratio of 1.20. Employers need skills now —not just in theory. This is why foreign worker numbers reached record highs and why "Specified Skilled Worker" visas surged in 2025. However, the number of Indian workers in Japan remains low compared to the potential. A corridor could improve the situation: it would standardize credit recognition, develop co-taught degrees in English and Japanese, and ensure paid placements in Japanese companies and public agencies. Make this path clear, and the numbers will increase.

Weak yen, tight labor: why the corridor suits Japan's economy

Policy goals should begin with demographics. Japan's workforce is shrinking, and companies face rising wage pressures as they update their IT and manufacturing systems. Many firms will continue to move some functions abroad. However, in the short term, a Japan-India education corridor that links classroom learning with practical work opportunities in Japanese supply chains offers a better solution. The corridor could transform today's sporadic recruitment into continuous cohorts. Each group would receive language training, technical education, and guaranteed on-the-job learning—across hospitals, factories, labs, and local governments. This is not charity; it is the most cost-effective method to enhance productivity, especially when capital investment is slow and demographic changes are limited. The corridor targets skill shortages without creating social tensions because participants arrive prepared for specific roles and backed by institutions on both sides.

The data support this approach. Since 2008, the number of foreign workers has quadrupled. "Specified Skilled Worker" holders alone reached 336,000 by mid-2025. Yet Indian involvement remains low, even as companies seek talent from India for engineering and digital skills. With a weak yen and tight margins, companies prefer reliable pipelines to bidding wars for scarce domestic hires. A corridor that establishes multi-year cohorts—and allows Japanese municipalities to co-develop training with Indian universities—addresses both cost and quality issues. It also promotes wage growth by alleviating blockages that hinder productivity. Making it easy to hire nurses trained in Japanese practices, welders certified to Japanese standards, and cloud engineers familiar with Japanese compliance would boost overall performance. Tight labor limits growth; reliable talent promotes it.

From CEPA to Quad: connecting the corridor to strategy

The diplomatic framework is already suitable. Trade remains steady but unimpressive—around US$21 billion in FY2024-25 (April–January)—yet Japan's investment in India is significant and growing. From April 2000 to December 2024, cumulative foreign direct investment stood at nearly US$43 billion, making Japan India's top bilateral development partner. These facts open opportunities for funding and governance. JICA can finance campuses, dormitories, and training centers. CEPA's committees can expedite the recognition of qualifications. Additionally, defense logistics access provides universities and think tanks with predictable avenues for collaboration in maritime security, cyber defense, and disaster response. The essential components are in place—it's time to connect them and center education.

Industrial policy makes the corridor essential. Japan is investing heavily in semiconductor production and advanced manufacturing. TSMC's Kumamoto facility has received over US$20 billion in significant government support. At the same time, Rapidus has secured multiple rounds of subsidies to develop next-generation chips. These initiatives need thousands of engineers, technicians, and operators. India can provide trained workers familiar with Japanese processes, safety standards, and quality checks. Quad agreements already promise talent development in "critical and emerging" technologies. Integrating the Japan-India education corridor into this commitment would turn semiconductor development into both a classroom and a factory. Set quotas for co-op placements from Indian institutions. Link visa approvals to completion of accredited courses and reward companies that host cohorts with tax credits based on training hours. This is how to turn state support into skills.

Japan's financial ties with India are also well-suited for this initiative. The Mumbai–Ahmedabad high-speed rail—primarily funded by Japanese ODA—requires a new generation of rail engineers, signaling experts, and rolling-stock technicians. Co-branded institutions along the corridor can train for these roles and contribute to project pipelines. These institutions should also be open to Japanese students, promoting mutual knowledge exchange. When Japanese cities face shortages of caregiving staff, Indian nursing colleges can facilitate joint research on elder care and robotics, and rotate students into local hospitals for practical experience. The corridor would not replace domestic training but would enhance it. Consider it a shared skills resource funded by ODA and managed under CEPA's framework.

What educators and policymakers should do now

Start by making scalable design choices. Set a five-year goal that generates real progress: increase Indian student enrollment in Japan from around 1,700 to 10,000 and place 50,000 Indian trainees and mid-career professionals in supervised, paid internships within Japanese institutions. These numbers are not ambitious when considering Japan's labor needs; they demonstrate a functional system. Next, link funding to measurable outcomes: offer micro-credentials co-signed by Indian and Japanese agencies, convert these into university credits, and establish recognized paths to residency for high-demand careers. Finally, ensure that every publicly funded Japanese project in India—rail, energy, digital—includes training facilities and teacher exchange programs. This creates capacity in both nations and raises quality standards.

Universities should take the lead. Focus on fields with clear regulations and strong demand: elderly care, mechatronics, welding, bilingual K-12 STEM education, marine logistics, cybersecurity, and AI operations. Develop dual-campus degrees with divided residency, shared intellectual property rules, and guaranteed scholarships funded by ODA and industry. Use Japanese language proficiency as an advantage, not as a barrier. Students who achieve B1/B2 proficiency should receive automatic stipends and signing bonuses. Local Japanese governments can co-support cohorts that fill existing vacancies in their healthcare systems, transportation networks, and data centers. The benefits are not just economic but social: fewer last-minute labor shortages, faster service improvements, and a fairer path for migrants who come ready to contribute and succeed.

Policy ministries must remove bureaucratic hurdles that impede progress. Establish a single digital portal for the Japan-India education corridor to manage visas, credit transfers, insurance, and worker rights. Set clear timelines: 30 days for course pre-approval, 15 days for evaluating employer sponsorships, and 72 hours for internship approvals linked to accredited degree programs. Expand trusted-sponsor status for universities and companies with strong compliance records. Integrate the corridor into Quad's technology and digital infrastructure working groups, ensuring that curriculum templates, credential systems, and cybersecurity standards are compatible from the outset. By doing this, the corridor becomes a regional asset rather than just a bilateral perk.

Anticipating the critiques

Critics might argue that more foreign workers would lower wages or crowd out domestic students. However, evidence suggests otherwise. Japan's labor market is tight, not weak. Blockages are hindering productivity and quality of service. A corridor that aligns training with job openings alleviates these issues. It supports wage growth instead of stifling it by allowing companies to expand where they currently face constraints. Others may express concerns about language and cultural barriers. That is precisely what the corridor aims to address—by integrating language education and support services into degree programs and by making hands-on experience part of the curriculum rather than an additional requirement. For those worried about over-reliance on India, remember that the corridor serves as a two-way connection. It should allow Japanese students and educators to explore Indian labs and clinics, and be governed by shared standards and joint evaluations. Evidence from Japan's existing programs shows that the demand for foreign workers has risen due to fundamental gaps; the focus should be on meeting these needs with quality and protection.

Consider the initial contrast: millions of foreign workers in Japan, yet only a few thousand Indian students. The message is clear. Demand is strong. The pipeline is narrow. Takaichi's commitment to continuity can be fulfilled if she chooses to prioritize capacity over symbolism. A Japan-India education corridor would link Japan's needs with India's capabilities. This connection would strengthen both economies and the regional landscape. It would build on CEPA, integrate into the Quad, draw on ODA, and deliver tangible benefits through real jobs and services. This is not a distant goal; it is a pragmatic plan that aligns institutions with incentives and skills in short supply. Implement it now while the yen is weak, the labor market is tight, and the semiconductor and rail development projects are in urgent need of talent. The longer Japan postpones, the more opportunities—and students—it risks losing to others. The corridor is the key. Open it wide.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2025, Oct. 21). Japan's parliament elects Sanae Takaichi as nation's first female prime minister.

Embassy of India, Tokyo. (2025, May). India–Japan Bilateral Relations.

Embassy of Japan in India. (2024, Oct.). Japanese Business Establishments in India (2024).

International Energy Agency. (2024). Japan–India Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (JICEPA). (Came into force Aug. 1, 2011.)

Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2020, Sept. 10). Agreement concerning Reciprocal Provision of Supplies and Services (ACSA) with India.

Japan Times. (2025, Oct. 31). Japan's September job availability ratio stays unchanged at 1.20.

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). (2025, Apr. 3). Operations and Activities in India FY2024–25. (Japan is India's largest bilateral ODA donor.)

Ministry of External Affairs, India. (2025, May). India–Japan Bilateral Relations (Trade in FY2024–25; ODA status).

NHSRCL. Project overview: Mumbai–Ahmedabad High-Speed Rail. (JICA ODA-financed project.)

Nippon.com. (2025, Feb. 27). Japan's foreign workers hit a new record of 2.3 million (as of Oct. 2024).

OECD. (2024). Recruiting Immigrant Workers: Japan 2024.

Reuters. (2024, May 31). Japan spent ¥9.79 trillion intervening to support the yen in May 2024.

Reuters. (2024, May 2). Japan likely intervened after dollar/yen spiked above 160.

Reuters. (2025, Oct. 10). Authorities may act if yen dives toward 160 per dollar.

State Department (U.S.). (2025, July 1). 2025 Quad Foreign Ministers' Meeting.

TSMC. (2025, Oct. 17). Business Overview 2024 / JASM investment exceeds US$20 billion.

White House (archived). (2024, Sept. 21). Fact sheet: 2024 Quad Leaders' Summit (talent development in critical and emerging tech).

Yomiuri via Asia News Network. (2025, Aug. 28). Indian students in Japan in 2024 academic year: 1,685.

Comment