Public Spending Efficiency Is the Growth Strategy

Input

Modified

Rising interest bills make public spending efficiency the growth strategy Prioritize smarter procurement, disciplined investment, and service productivity over sector wish lists Measure, review, and reallocate to what works to free fiscal space

A single number illustrates the stakes. In 2024, governments across the OECD paid interest equal to 3.3% of GDP, which is more than their total defense budgets. Every financial decision now competes with that expense. The old idea of "spend more on X" loses impact when a larger portion of revenue fails to reach classrooms, hospitals, or labs. The way forward is not a new list of sectors but a new way of operating. We need to build public spending efficiency into the budget itself. This includes procurement that achieves more for less, investment systems that prioritize high-value projects, and service delivery that increases output with the staff and resources already funded. Debt in advanced economies remains around 110% of GDP, so the cost of inaction is high. Each year that efficiency gains are missed, the interest continues to accrue, and the opportunity for future investments dwindles. Efficiency is not just a buzzword; it’s the only way to stretch limited public funds.

Why public spending efficiency must replace sector lists

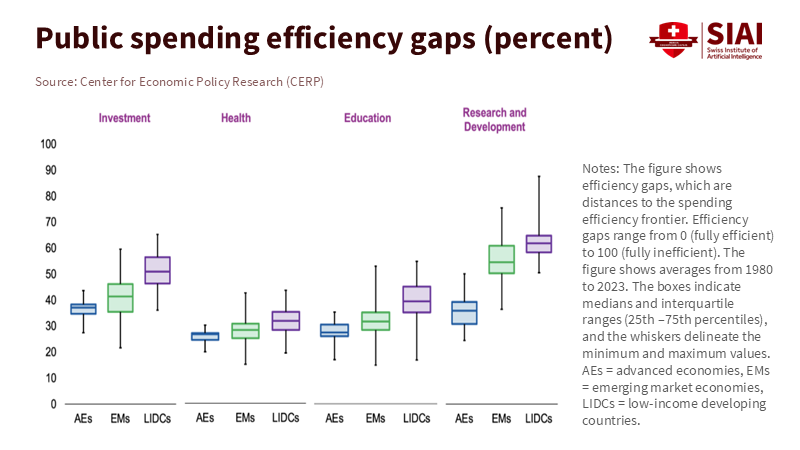

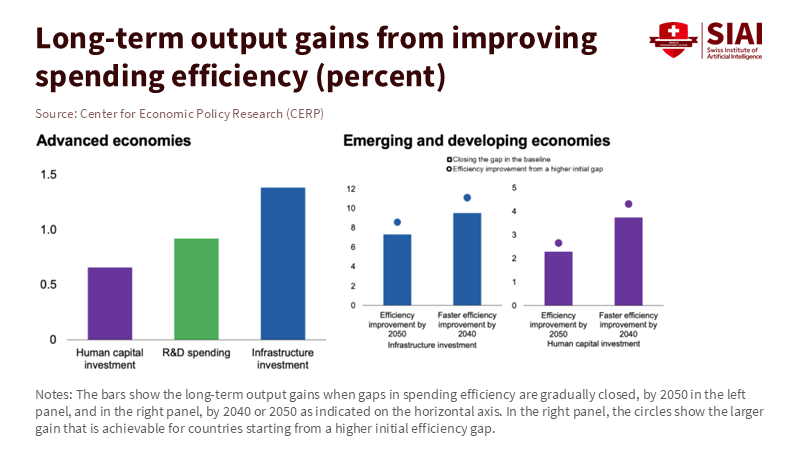

Discussions often begin with different sectors: infrastructure, education, health, and research and development. These sectors are essential, but labels alone don't form a strategy when interest costs rise and fiscal space tightens. The key is public spending efficiency, which increases the return on each public euro across all programs. It’s like adjusting the government’s own production capacity. This adjustment has become urgent. Advanced economies head into 2025 with gross debt still near 110% of GDP, and global debt ratios are drifting back to pandemic levels. Low-interest rates are disappearing; refinancing costs are high; and central banks are no longer the primary buyers. The message is clear: we can’t achieve growth just through volume; we need more innovative design. This requires fewer automatic budget increases and more careful reallocation of funds. It also calls for building institutions that direct funds to the highest-value uses within any sector while moving away from low-value activities, even if they are politically favored. Policymakers now must shift their focus from “how much for sector A versus B” to “what does each additional public euro achieve, and how do we verify its effectiveness?” International cooperation is crucial in this endeavor, as it can help address global debt issues and foster collaboration in implementing efficiency measures.

Public spending efficiency also enhances trust in democracy. Recent research using OECD data indicates that higher spending efficiency corresponds with greater trust in government. Trust is not a trivial aspect; it signals performance, reduces risk, and creates space for long-term reform. When citizens observe improvements like better schools, faster permits, and shorter waiting lists—all achieved within existing budgets—they are more willing to accept the tougher adjustments that efficiency demands in other parts of the government. Therefore, the political benefits of efficiency are two-fold: it frees up resources. It builds the necessary support for reallocating them. This is vital as fiscal rules tighten in Europe and pressures from aging populations, defense needs, and climate change grow. Public spending efficiency can play a significant role in addressing these societal challenges, underscoring its broader impact and relevance.

Public spending efficiency starts with procurement and investment

Public procurement is the budget’s biggest tool, often going unnoticed. It makes up roughly 12–13% of GDP across the OECD. Minor improvements in this area can lead to significant, ongoing savings. Studies from various contexts highlight what is achievable. Digital procurement platforms and centralized purchasing can lower prices by a few percentage points on average, with even greater impacts in complex categories or when buyers are fragmented. Italy’s centralized purchasing system has led to considerable indirect savings, even among agencies that operate outside the main framework, as better market information and reference prices improve negotiations. Ukraine’s ProZorro system has increased competition and accountability under pressure, with a growing number of competitive tenders. These changes are not one-off successes but ongoing shifts in cost structures when integrated into rules, data, and market designs. The implication for the budget is straightforward: freeing even 1% of GDP from procurement inefficiencies can finance significant educational or health reforms without new taxes.

Public investment requires the same level of discipline. The IMF’s latest infrastructure assessments reveal a substantial efficiency gap, and closing it could increase the effective output of investments by double-digit percentages without requiring additional funds. Countries that enhance project evaluation, connect funding to life-cycle asset management, and process projects through independent reviews can build more capacity on time and within budget. The lesson is clear. Before advocating for larger capital budgets, we should demonstrate that the next euro of investment will bring the anticipated benefits on schedule. This also means identifying and cutting losses early when projects miss key milestones or when actual demand falls short of forecasts. In today’s tighter interest environment, the benefits of such discipline multiply: better project selection lowers initial expenditures and the subsequent interest costs.

The digital backbone plays an important role here as well. Countries that invest in key government systems—such as identity management, payments, and data sharing—reduce administrative hurdles across services. Estonia is a well-known example, with its nearly universal digitization of services and secure data exchange resulting in saved resources and added convenience. Specific figures vary, but the trend is consistent: fewer trips, fewer mistakes, quicker processing, and more intelligent targeting. For finance ministries, the key question isn’t whether to “go digital,” but how to manage those investments to foster efficiency rather than create new barriers. Capital budgeting should consider digital public infrastructure on the same level as traditional infrastructure, with the same level of scrutiny applied to roads or hospitals.

Public spending efficiency demands constant measurement and review

Efficiency can’t exist without measurement. This starts with productivity in the public services we currently fund. The UK now publishes quarterly data on public service productivity. The findings are concerning: despite a partial recovery since the pandemic, productivity in 2024 remains below 2019 levels, with healthcare being a notable drag. This isn’t limited to the UK; it serves as a warning about the consequences of inputs growing faster than outputs under operational strain. Regularly publishing credible productivity data creates pressure to refine workflows, modernize scheduling, and target interventions effectively. It also elevates the quality of budget discussions. When productivity declines, simply adding funds without reform isn’t wise; it’s a sign of stagnation.

Spending reviews turn that pressure into actionable choices. They are now a standard part of budget systems in many OECD countries, with the Netherlands exemplifying annual, structured reviews. The goal is not just to cut spending but to reallocate resources: identify low-impact programs, scale them down or redesign them, and move resources to higher-impact activities. The structure of these reviews matters. They should be promoted from the center of government while still involving line ministries, adhere to common evidence standards, and automatically inform the next budget round. When executed well, they create a consistent evaluation process within the government. Programs that can’t demonstrate results lose funding; those that prove adequate gain support. This routine is how public spending efficiency can become a habit rather than just a headline.

Evaluation must also accelerate. Conventional impact evaluations can take too long and lack breadth. Finance ministries should broaden their evaluation toolkit: use rapid quasi-experimental methods when possible; consider “pay for spread” pilots that reward widespread adoption rather than just limited successes; and implement digital dashboards that monitor both costs and service outcomes in near real-time. The goal is not flawless measurement; it’s timely decision-making. When a reform shows promise, we should invest further; when it fails, we need to stop. This requires data standards, shared identifiers, and straightforward legal guidelines for data use across agencies. These aren’t just academic steps; they’re the essential connections that direct funds to what actually works.

Scaling public spending efficiency through cross-learning and digital tools

Public spending efficiency grows fastest when governments learn from each other across sectors and borders. Health systems have developed value-based payment models that link funding to outcomes; transportation agencies can apply a similar approach to maintenance contracts. Education systems have created early-warning tools for targeted tutoring; employment services can apply similar frameworks to avoid long-term unemployment. Procurement bodies have utilized framework contracts and dynamic purchasing systems to boost competition, and municipalities can collaborate to purchase clean energy or IT products under better agreements, as illustrated by Italy’s experience. This kind of cross-learning isn’t about simply copying ideas; it’s structured adaptation. The center of government should maintain a “methods lab” that identifies effective practices, tailors them to local needs, and finances the initial implementation across agencies.

Digital government platforms facilitate this sharing process. The World Bank’s GovTech Maturity research shows how shared systems for payments, identity management, case handling, and analytics enable services to leverage common frameworks rather than build them from scratch. When those frameworks are secure and user-focused, frontline teams can implement improvements more quickly and at a lower cost. Procurement data that connects to budgets and payments makes it easier to spot collusion or overpricing; identity and consent frameworks enable targeted benefits without creating parallel verification systems; cloud standards reduce wasted infrastructure and speed up deployment. Even in lower-income scenarios, documented cost savings from shared cloud or e-procurement platforms are now available. The trend is consistent: shared platforms plus transparent governance lead to lower costs and better service quality. This is public spending efficiency in action.

A final caution is warranted. Industrial policies and sector subsidies are becoming popular again. Some may be justified, particularly for basic research and network infrastructure. However, the IMF and other analysts caution against broad, poorly targeted subsidies that hinder private initiatives and promote rent-seeking. The efficiency test applies here as well. Support instruments should be open to competition, time-limited, and evaluated against apparent alternatives. When they are ineffective, we need to reallocate resources. When they succeed, we can scale them—but only with robust measurement. Efficiency serves as a boundary that keeps ambition from turning into waste.

The near-term playbook for public spending efficiency

The next budget cycle should prioritize public spending efficiency from the beginning. Begin with procurement: mandate digital tendering, publish reference prices, and expand central frameworks in areas with fragmented buyers. Ensure competition by default and make results public in machine-readable formats. Move on to investment: require independent appraisals, publish pipelines with cost-benefit metrics, and assess project funding based on credible reviews at each stage. Transition to services: establish unit cost baselines, publish productivity dashboards, and reward teams that increase output while maintaining quality. Support all these efforts with digital public infrastructure—identity management, payments, data sharing—and governance that prevents the creation of new silos. Then, institutionalize spending reviews that integrate these elements and allocate resources based on evidence. None of these steps necessitates a radical overhaul of the social contract. They only require steady, diligent effort. The returns will be seen year after year.

The interest costs indicate that we are out of time. When governments spend more on debt service than on defense, there is little room for flexibility. The only reliable way to finance today’s priorities and tomorrow’s opportunities is to enhance public spending efficiency throughout the board. This means being more thoughtful about purchases before increasing spending, making investments only when good governance is assured, and managing services with a focus on productivity rather than just coverage. It requires regular spending reviews that reallocate funds to what is effective, and digital platforms that enable each agency to operate on shared foundations. The benefits are immediate fiscal space and long-term trust. The danger of inaction is a gradual tightening as interest costs consume future resources. If we act now, we can change this trend. We can transform the budget from a collection of promises into a mechanism that delivers results. Public spending efficiency is not merely a technical detail; it is the growth strategy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Afonso, A., Jalles, J. T., & Venâncio, A. (2024). A tale of government spending efficiency and trust in the state. Public Choice, 200, 89–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-024-01144-6.

Bosio, E. (2023). The Investment Case for E-Government Procurement: A Cost-Benefit Analysis. Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. (2025). The impact of the ProZorro procurement system on the Ukrainian economy. Law in Transition.

International Monetary Fund. (2023). Benchmarking Infrastructure Using Public Investment Efficiency. IMF Working Paper.

International Monetary Fund. (2024). Fiscal Monitor: Fiscal Policy in the Great Election Year. Executive Summary.

International Monetary Fund. (2025, October). Fiscal Monitor: Spending Smarter—How Efficient and Well-Allocated Public Spending Can Boost Growth. Chapter materials.

International Monetary Fund. (2025). World Economic Outlook—Data Mapper (General government gross debt, advanced economies).

Netherlands Country Note. (2025). In OECD Government at a Glance 2025.

Office for National Statistics (UK). (2025). Public service productivity, quarterly, UK: April to June 2025.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education. OECD Publishing.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2024–2025). Digital Economy Outlook 2024; Digital Public Infrastructure for Digital Governments. OECD Publishing.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2025). Global Debt Report 2025—press materials and report PDFs.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2025). Government at a Glance 2025—Size of public procurement.

OpenICPSR. (2024). Indirect Savings from Public Procurement Centralization (Italy).

ProZorro. (2025). Volume of competitive procurement in Ukraine 2023–2024.

Reuters. (2025, March 20). Global debt exceeds $100 trillion as interest costs keep rising, OECD says.

World Bank. (2023–2024). GovTech Maturity Index—reports and notes.

World Bank. (1997). Efficiency of Public Spending in Developing Countries: An Efficiency Frontier Approach. Policy Research Working Paper 3645.

Comment