Tariffs Won't Fix the Deficit; Talent and Teaching Will Build the U.S.'s Comparative Advantage

Input

Modified

Tariffs won’t fix the deficit; they raise prices for U.S. consumers America’s comparative advantage is in services and ideas like finance, software, and IP Strengthen K-12 math and expand high-skill visas to grow talent and exports

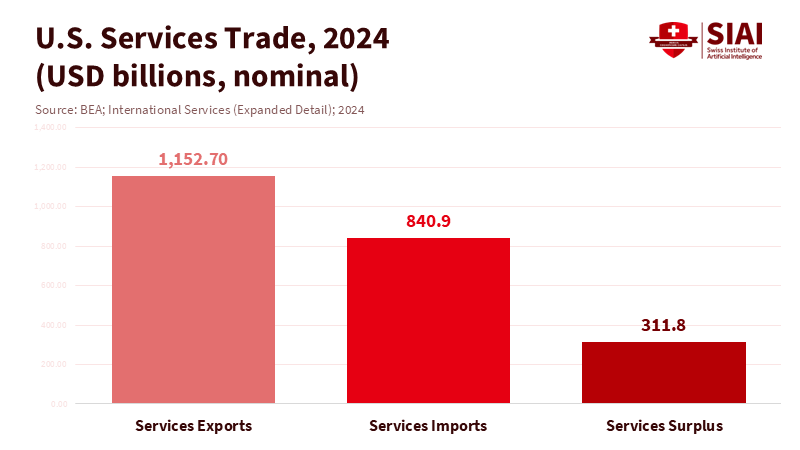

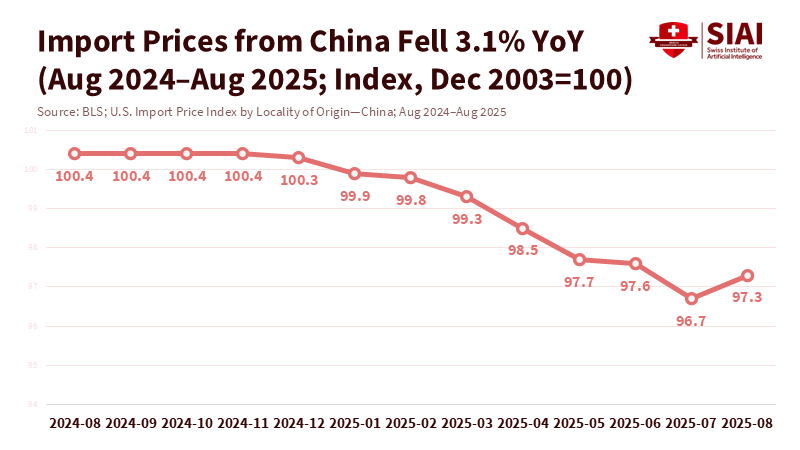

A single number frames the choice ahead: 3.1%. That was the year-over-year change in the U.S. import price index for goods from China in August 2025. Even as Washington raised duties again, the price of what American households buy from China kept falling. Cheap, acceptable products keep arriving, and people keep buying them. The result is predictable: a $295.5 billion U.S. goods trade deficit with China in 2024. At the same time, the United States posted $1.15 trillion in services exports and a large services surplus, driven by intellectual property, finance, software, cloud, and higher education. The lesson is not new, but it is urgent: tariffs won't fix a structural gap that shows where each economy is strong. We should stop pretending that higher border taxes will change that. We should focus on U.S. comparative advantage—in ideas, services, and cutting-edge technologies—by improving how we teach and who we allow in.

U.S. comparative advantage is in services and ideas

The pattern is hiding in plain sight. The U.S. sells the world financial services, intellectual property, business services, cloud software, and education on a large scale. In 2024, services exports reached $1.15 trillion against $840.9 billion of imports, leaving a surplus that offsets some of the goods deficit. Payments for the use of U.S. intellectual property alone ran in the tens of billions per quarter. This is what U.S. comparative advantage looks like in the twenty-first century: value from design, algorithms, brands, standards, and research, not low-margin assembly. A decade-long body of research supports this point. In U.S. bilateral services with China and India, the United States maintained an edge in most categories, even as rivals gained ground in a few digital niches. The service's advantage is not guaranteed, but it is real—and it is where policy should focus.

The counterpart is just as transparent. Americans import many consumer goods because they are inexpensive and suitable for daily use. Import prices from China fell 3.1% over the year to August 2025 and declined on a twelve-month basis for much of 2025. That price reality supports household budgets and business profits. It also explains why tariffs have difficulty changing trade flows for the long term. Households substitute products, firms adjust routes, and global supply chains adapt. The result is a persistent bilateral deficit with China that widened again in 2024 after declining in 2023, despite higher duties on targeted sectors such as electric vehicles and batteries. The import basket and the production map reflect deep specialization, not a policy failure that a duty can reverse. U.S. comparative advantage is the lever; tariffs are not.

Tariffs tax households and miss the structural point

We also know who pays. Careful estimates of the 2018–2019 tariff rounds found near-complete pass-through into U.S. import prices, reducing real income and raising costs for consumers and firms. The logic hasn't changed. In 2025, the Congressional Budget Office projected that broad tariff hikes would lower real GDP, raise inflation by about 0.4 percentage points in 2025 and 2026, and cut purchasing power, even as they reduced the federal deficit on paper. Other credible models show similar results. A tax on imports is a tax on American users of those imports. It is a simple point, but it keeps getting lost amid the noise. When we tax inputs like steel, chips, tools, and specialized machinery, we also tax U.S. exporters that need them to compete abroad. That is the opposite of a strategy to grow exports out of a deficit.

A newer body of research adds another structural reason to avoid blanket duties. When a tariff raises the domestic currency, it can worsen the value of a country's net foreign assets, reducing any "optimal tariff" benefits and shrinking welfare. That is why the theoretically "right" tariff is much smaller once gross external balance sheets are taken into account. Recent work shows that the optimal U.S. tariff could be a fraction of textbook levels once valuation effects are considered, and that efforts to "close" the deficit through tariffs work—if at all—only through costly financial channels rather than trade volumes. The 2025 episode, sometimes called "Liberation Day" in policy circles, highlighted how exchange-rate swings can dominate trade logic. We should not design a household-taxing policy around a shaky financial lever. We should build up a U.S. comparative advantage instead.

Talent policy is trade policy: fix schooling and the H-1B choke point

If the United States wants to sell more of what the world buys, it must enlarge the pipeline of people who create it. Here, the numbers are stark. Foreign-born scientists and engineers make up 43% of U.S. doctorate-level S&E workers, and temporary visa holders earn about 35% of U.S. S&E doctorates, with even higher shares in computer science and engineering. In 2022 alone, international S&E graduate enrollment surged to nearly 310,000, driven by master's students in computing and engineering. The depth of the talent pool is, therefore, a policy choice. Right now, the bottleneck is not talent supply; it is the limits and friction in how we allow talent to stay. A 2024 rule improved the H-1B selection process by focusing on unique beneficiaries, but the numerical cap remains frozen at 85,000, far below demand and misaligned with national needs. If we restrict the people who power the U.S. comparative advantage, we limit growth.

The education system needs the same structural realism. In PISA 2022, U.S. 15-year-olds scored around the OECD average in mathematics and above average in science and reading, but the math performance gap with top systems remains wide. That gap shows up years later in undergraduate preparation and in dropouts from demanding majors. We do not need more slogans about STEM; we need consistent improvements in K–12 math instruction, stronger early algebra pathways, and more extensive teacher support—especially in schools that serve low-income students. That is not protectionism; that is the long game. While these reforms accumulate over time, we should stop turning away graduate-trained engineers and computer scientists who are already studying at U.S. universities. Expand advanced-degree exemptions, create a skills-based "startup-founder" track, recapture unused visas, and clear green card backlogs. Education, combined with high-skilled immigration, is how we can quickly scale the U.S. comparative advantage.

Export more by leaning into the U.S. comparative advantage

A strategy to boost exports out of the deficit begins where the U.S. is strongest. Services are growing, digitally delivered, and heavily driven by standards. They scale with human capital and with trust in contracts, data protection, and intellectual property. That is the domain of U.S. comparative advantage. Start with export finance and market access. Expand the mandates of Ex-Im Bank and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation for software, AI safety tools, and climate-tech services, not just big hard-asset projects. Promote digital trade chapters with partners that will agree to them, building clear, reciprocal rules for cross-border data flows. Invest in the infrastructure: cloud regions, subsea cables, secure interoperability, and mutual recognition for professional services. Each of these moves lowers fixed costs for small U.S. firms that want to sell abroad. Each one helps turn skills into exports.

Then address the cost side for exporters. Tariffs on targeted Chinese inputs—semiconductors, batteries, solar cells, cranes—are now much higher. Policymakers claim they are precise. Maybe. But they also risk raising costs for U.S. firms that build clean-tech systems for global markets. A cleaner approach is to focus defensive tools on specific national-security chokepoints while keeping the parts of the worldwide system that lower costs for U.S. producers. Use investment screening for actual security threats. Keep tariff exclusions open and fast for capital goods and intermediate inputs that support export sectors. The goal is to help U.S. firms price competitively abroad while keeping domestic inflation low. That is the logic of U.S. comparative advantage: protect what matters; buy what is cheaper elsewhere; sell more of what only you can do.

The 3.1% drop in Chinese import prices over the past year is not a quirk. It is a sign that specialization still works. Americans choose low-cost goods because they free up money for services and innovation, which the U.S. excels in. Tariffs cannot erase that reality without taxing households and shrinking the overall economy. The way forward is to grow out of the deficit by investing in the U.S. comparative advantage. That means teaching math more effectively in middle school, providing adequate teacher support, and aligning high school coursework with the skills colleges and employers actually need. It means expanding the advanced-degree exemption and adjusting or redesigning the H-1B cap so we stop sending trained talent away. It means clearing green card queues, speeding up research visas, and focusing on services exports rather than taxing inputs. The goal is clear: more American ideas sold to the world. If we get talent and teaching right, the trade balance will take care of itself—and so will household welfare.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2019). The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on U.S. Prices and Welfare. NBER Working Paper 25672.

BEA (2025). U.S. International Transactions, 4th Quarter and Year 2024. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

BEA (2025). International Services (Expanded Detail). U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

BLS (2025). U.S. Import and Export Price Indexes, August 2025. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

CBO (2025). Budgetary and Economic Effects of Increases in Tariffs. Congressional Budget Office.

CEPR VoxEU (2025). Itskhoki, O., & Mukhin, D. Tariffs, global imbalances, and the dollar. 7 November 2025.

Census Bureau (2025). Trade in Goods with China (2023–2025). U.S. Census Bureau.

DHS (2024). Improving the H-1B Registration Selection Process and Program Integrity (Final Rule). Department of Homeland Security / USCIS.

NFAP (2025). The Importance of Immigrants and International Students in U.S. Higher Education and the U.S. Economy. National Foundation for American Policy.

NSB/NSF (2024). The State of U.S. Science and Engineering 2024 (Key Takeaways). National Science Board / National Science Foundation.

NSB/NSF (2024). The STEM Labor Force (NSB-2024-45). National Science Board / National Science Foundation.

OECD (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education; United States country note. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

USTR (2024). FACT SHEET: President Biden Takes Action to Protect American Workers and Businesses from China's Unfair Trade Practices; Section 301 Modifications Determination. Office of the U.S. Trade Representative / White House.

USTR (2025). The People's Republic of China – Trade Facts. Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

World Trade / USITC (2024, 2025). Recent Trends in U.S. Services Trade (Annual Reports). U.S. International Trade Commission.

Comment