Pacific Climate Education Is the Missing Pillar of Island Resilience

Input

Modified

Climate finance must fund people, not just projects Put Pacific climate education at the center Tie every grant to learning-days and local ownership

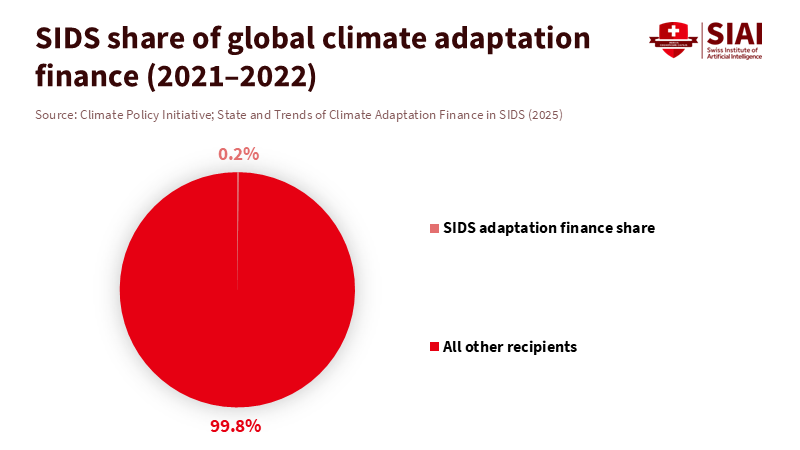

In a year when the oceans in the South-West Pacific set new heat records, a crucial statistic stands out: Small Island Developing States receive only about 0.2% of global climate finance for adaptation, which amounted to just over $2 billion in 2021-2022. This is even more alarming given that these communities are among the world's most vulnerable. The urgency of the climate crisis cannot be overstated. This funding is not just insufficient; it indicates a significant flaw in the system. Financial support tends to go to specific projects rather than to the systems that sustain them, such as public administration, maintenance, teacher training, and data services. We continue to fund seawalls while neglecting the human systems that run schools, clinics, and utilities. The outcomes are predictable. In places like Vanuatu and Fiji, storms destroy classrooms, children are forced to learn in tents, and literacy gains erode with each cyclone season. If we want climate finance to succeed in the Pacific, prioritizing Pacific climate education must be non-negotiable.

Reframing the Problem: From Project Dollars to System Capacity in Pacific Climate Education

The standard narrative suggests that the Pacific's main issue is a lack of funding. While that lack is real and significant, the deeper issue is capacity: there are too few engineers to design cyclone-resistant schools and water systems, not enough local procurement expertise to ensure spare parts reach outer islands, limited meteorological and educational data to schedule safe school calendars, and insufficiently trained school leaders to apply climate-ready operations. The World Meteorological Organization reports that sea levels in parts of the western tropical Pacific have risen 10–15 cm since 1993, nearly double the global rate, and marine heatwaves have approximately doubled in frequency since 1980 (WMO, 2024). These risks are tangible. Without skilled workers and strong institutions, every financed asset risks becoming a stranded investment.

This capacity issue isn't coincidental. A century of colonial rule standardized European governance and education across the islands, but rarely established local control over technical systems. Historical maps from 1901, 1951, and 2001 illustrate this: the Pacific was managed as a patchwork of European (and briefly Japanese) jurisdictions, each imposing its own bureaucratic systems. Those systems still shape today's education frameworks and their supply chains. The aim is not to debate history but to acknowledge that a legacy of external design and internal dependence continues—and that climate finance that overlooks this will fall short. Our proposed policy change puts Pacific climate education—focusing on teacher preparation, vocational training, school leadership, and climate literacy—at the heart of adaptation. This way, every dollar spent on infrastructure contributes to sustainable, locally managed resilience, highlighting the crucial role of local leadership in this process.

The Evidence: Climate Shocks Are School Shocks—And They Are Accelerating in the Pacific

Global climate events disrupted education for at least 242 million students in 2024, affecting one in seven school-aged children worldwide. The Pacific is particularly vulnerable to such disruptions. Cyclones Kevin and Judy struck Vanuatu within 48 hours of each other in 2023; Cyclone Harold in 2020 damaged or destroyed hundreds of schools; and a significant earthquake in late 2024 rendered many more buildings unsafe. The lesson is clear: if schools fail, learning fails; and if learning fails, every other adaptation policy loses its workforce. We cannot effectively staff early-warning offices, water authorities, or fisheries laboratories if children miss out on months of education during hazard seasons.

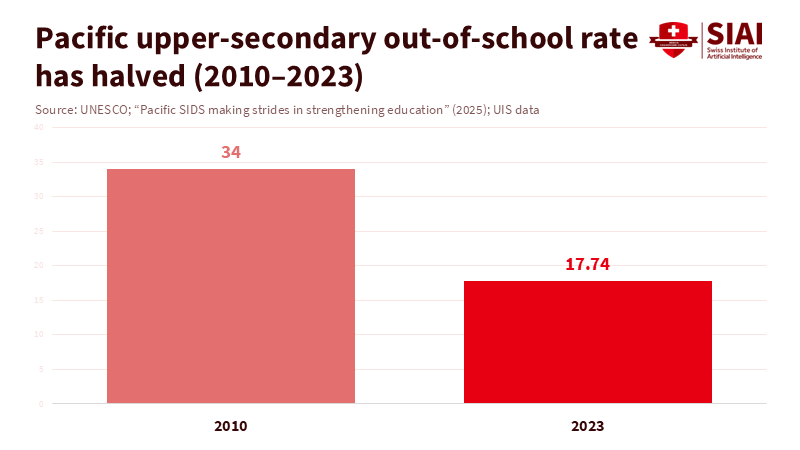

There is some progress to build upon. The Status of Pacific Education Report 2024 states that the region has halved the upper-secondary out-of-school rate since 2010, bringing it down to around 18% in 2023. This is a real victory achieved through hard work—free basic education in more countries, stronger assessment systems, and better support for teachers. However, this progress is fragile. The WMO notes that Pacific sea surface temperatures have risen three times faster than the global average since 1980, with marine heatwaves becoming longer and more intense. As floods, heat, and storms become more severe, school calendars, transport systems, water safety measures, and building codes must adapt simultaneously. This presents an educational challenge before it becomes a construction issue. Pacific climate education serves as the vital link.

What Works: Make Climate Finance Pay for People, Not Just Projects, in Pacific Climate Education

We need to divert a significant portion of adaptation funding toward the people and processes that ensure education continues under climate stress. The metric should be straightforward: funds that reliably secure learning days during hazard seasons. Three areas stand out for investment. First, support school-centered early warning systems and continuity plans. Currently, only about a third of Small Island Developing States have comprehensive multi-hazard early-warning systems. School-specific protocols can swiftly translate forecasts into staggered closures, water delivery schedules, or alternative sites. Second, fund vocational training and teacher colleges to focus on climate-ready operations: solar-powered micro-grids for school clusters, rainwater harvesting, heat-safe classroom designs, and affordable shade and ventilation improvements. The European Union-UNICEF €10 million partnership to transform Vanuatu's schools into climate-resilient shelters offers a promising example by combining infrastructure improvements with training and governance. Third, bring back regional data platforms that link meteorological services with education ministries and local school leaders, making sure decisions are driven by real exposure, not averages. This approach can be efficient: shared dashboards, simple heat index thresholds, and SMS alerts can help maintain learning days at scale.

The financing system needs to change to facilitate these strategies. CPI has shown that adaptation finance for Small Island Developing States represents a tiny fraction of global financing. Meanwhile, the Loss and Damage Fund remains politically unstable; the United States' withdrawal in 2025 halted momentum just as vulnerable nations needed clear, long-term support. One possible solution is to incorporate education resilience lines into every national adaptation plan and donor country strategy for the Pacific. Another is to ensure that large infrastructure grants in the region set aside a fixed share—perhaps 10-15%—for Pacific climate education, including training for school leaders, curriculum development, and vocational programs directly related to financed assets. This is not an optional extra; it is what differentiates functioning infrastructure from failing infrastructure. The OECD's 2023 guidelines on capacity development for Small Island Developing States support this approach: fund access to climate data and services, collaborate with non-government partners, and deliver through regional platforms. This is where the education sector has a distinct advantage.

Accountability and Equity: A Post-Colonial Responsibility to Build Pacific Climate Education

There is both a moral and a practical argument for this approach. Many structures in Pacific education and governance were established during European rule, and their limitations persist today. The duty of former colonial powers—and today's high-emitting countries—is not only to provide funding but also to share capabilities. This includes ongoing scholarships for Pacific educators in climate-related fields, funded positions at island universities focused on school operations and disaster-risk education, and multi-year placements for master trainers who work in tandem with ministries rather than relying on temporary consultancies. It also requires using regional organizations—such as the Pacific Community's EQAP—to set standards and manage shared procurement for climate-ready school materials, ensuring that remote islands have access to the same quality as capitals.

Equity also requires leadership from Pacific voices. Research shows a consistent under-representation of Pacific scholars in teaching and writing about Pacific history and policy. This gap undermines legitimacy and learning. Climate curricula, hazard drills, and language decisions work best when they come from local educators who understand community risk patterns and cultural practices. When we speak of Pacific climate education, we mean programs designed, taught, and owned by the islands—supported by long-term funding. There are early signs of this shift: the Climate Smart Education Systems initiative launched by the Global Partnership for Education in 2023 responds to strong demand from countries and focuses on integrating climate risk management into education systems. If we expand this approach, fund it for a decade, and tie it to measurable learning-day outcomes, we can make a significant impact.

Anticipating the Critiques—and Rebutting Them with Evidence in Pacific Climate Education

One criticism is that schools should prioritize every available dollar for physical defenses and relocation; schools can wait. The evidence counters this view. Without functioning schools, we cannot maintain seawalls, operate desalination plants, or run evacuation centers. After Cyclone Harold, emergency assessments revealed that tens of thousands of students and teachers were displaced and that hundreds of schools were damaged, disrupting education. The economic and social consequences accumulate—children lag, caregivers lose work hours, and local governments struggle with staffing. In tight budgets, lost learning days become a hidden driver of long-term costs.

Another critique is the risk of capacity traps: funding training may result in ineffective workshops with little impact. This is a design issue, not a reason to avoid investment. Link spending on Pacific climate education to practical, embedded outputs—for example, granting certification to a school leader only when her cluster successfully conducts a heatwave drill and maintains attendance above a specific threshold during hot weather. Create micro-accreditations focused on tasks that protect learning days, such as generator upkeep, water quality testing, shaded playground design, or cyclone preparation checklists. UNICEF's Vanuatu program serves as a model: it combines infrastructure improvements with protocols that transform schools into multi-hazard shelters. If we invest in resources, we will only get workshops. If we focus on protecting verified learning days, we will achieve resilience.

A final critique addresses a geopolitical issue: some argue that framing responsibility around colonial legacies complicates climate finance. The history is political already. The Pacific accounts for 0.02% of global emissions but faces disproportionate risks; half its infrastructure is within 500 meters of the sea. European systems have long defined governance and education on the islands. Acknowledging this history clarifies our responsibilities today: provide stable, long-term funding and shared ownership, enabling Pacific educators to take the lead. This is not about guilt; it's about effective policy.

What Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers Should Do—Now—on Pacific Climate Education

First, make climate-ready operations a fundamental competency for school leadership. Ministries should update head-teacher standards to include skills like heat-safe scheduling, early-warning protocols, backup water management, and risk communication. These are skills that can be taught. Teacher colleges and leadership training programs can incorporate these into both pre-service and in-service training over the next two years, using shared modules from regional organizations like EQAP or universities in Fiji and Samoa.

Second, ensure long-term financing is locked in. Donors should identify specific lines for Pacific climate education in every adaptation grant and national loan for the region, setting a minimum allocation of 10% for staffing, training, and local curriculum development. This could be integrated into Asian Development Bank and World Bank operations and tracked through a shared results framework that measures learning days saved per $100,000 invested.

Third, use schools as climate service hubs. Many islands lack meteorological stations and data literacy. Equip school facilities with basic sensors and a simple data platform connected to national services. Students can assist in maintaining devices and in interpreting readings, integrating climate science into daily practice, and improving local decision-making on closures, water, and shade. The WMO's Early Warnings for All initiative provides a natural opportunity for this integration.

Fourth, prioritize language and culture in education. A curriculum that explains cyclone physics in local languages, incorporates village landmarks into evacuation maps, and draws on traditional coastal knowledge will resonate more effectively and spread faster than generic programs. The Pacific has already increased access to basic education; this is the next critical step. This approach also helps us move beyond imported content to build lasting legitimacy for climate-aware education.

Finally, measure what's important. Ministries should maintain a simple dashboard tracking metrics such as attendance during hazard seasons, the time taken to reopen after events, water safety compliance, indoor temperature readings, and the proportion of schools with functioning shade and ventilation. Share this information publicly. When the preservation of learning days becomes the focus, funding will follow.

From 0.2% to 100% Ownership—Financing the People Who Keep Schools Open

We started with a stark fact: only 0.2% of global climate finance for adaptation reaches the small island states that face some of the most significant risks. In the Pacific, this gap shows up in one of the most important places—the classroom. Sea levels are rising faster than the global average, heat is increasing, and storms are becoming more frequent. We cannot build walls to protect ourselves if we cannot educate our way forward. A resilient Pacific must have climate education that is funded, managed, and led by island educators —not borrowed for a trial and forgotten in the next budget cycle. There is no mystery in the solution. Link a steady portion of adaptation finance to leadership, TVET, and data programs that protect school days. Include these measures in national plans and donor agreements, and hold every project accountable—does it keep schools open, safe, and teaching after the next storm?

This is how we shift from charity to building capacity, from guilt to governance, and from stranded assets to thriving systems. The Pacific has proven it can broaden access and improve education even during tough times. Provide it with the tools, training, and authority to complete the task. Support the people who maintain power, ensure clean water, and keep schools open. If we do this, the following statistic we highlight won't be 0.2%. It will be 100% ownership, with a generation learning in safe, comfortable, climate-ready schools across the islands.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2024). Asia-Pacific Climate Report: Catalyzing Finance and Policy for Adaptation. (News coverage summary of financing needs up to $431 billion annually, 2023–2030).

Climate Policy Initiative (CPI). (2025). State and Trends of Climate Adaptation Finance in Small Island Developing States. Key finding: SIDS received ~0.2% of global climate finance; just over $2 billion annually in 2021–2022.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia) – DFAT. (2020–2023). Tropical Cyclone Harold updates and education cluster assessments.

Global Partnership for Education (GPE). (2024). Climate Smart Education Systems Initiative—Bi-annual Progress Report.

The Guardian. (2025, January 25). 'Never seems to end': Vanuatu rebuilds again after December 2024 quake.

NRDC. (2025). Climate Funds Pledge Tracker. Adaptation Fund cumulative pledges by end-2024.

OECD. (2023). Capacity Development for Climate Change in Small Island Developing States.

Te Ara—The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. (2024). Colonial control in the South Pacific (interactive map, 1901/1951/2001).

UN (United Nations). (2025). Vanuatu: Tackling the impact of natural disasters by building a resilient education system.

UNESCO. (2024/2025). Status of Pacific Education Report 2024; Pacific SIDS strengthening education (2025 note).

UNFCCC. (2024–2025). Fund for responding to Loss and Damage—Board meetings and governance.

UNICEF. (2025). Global snapshot: Climate-related school disruptions in 2024. (242 million students disrupted).

UNICEF Pacific. (2025). Vanuatu's schools to transform into safe havens—€10 million EU partnership.

WMO (World Meteorological Organization). (2024). Climate change transforms Pacific Islands (press release; sea-level rise 10–15 cm; SST warming ~3× global; marine heatwaves doubling); (2025). State of the Climate in the South-West Pacific 2024 (global mean sea-level ~4.7 mm/yr, 2015–2024).