Debt Stigma and the Speed of Money: A Policy Lever Hiding in Plain Sight

Input

Modified

Debt stigma slows borrowing and drags on money velocity Purpose-framed, safeguarded credit boosts productive investment in education and firms Use macroprudential guardrails to lift growth without fueling bubbles

Debt stigma isn't just a personal issue; it has a broad impact on the economy. In the United Kingdom, half of the people who are behind on credit payments have reported suicidal thoughts. This stark reality illustrates the shame and fear associated with overdue notices and collection calls. This moral burden influences not just households deciding whether to borrow but also businesses and voters considering public investments. It affects how quickly money flows through the economy, how much risk people are willing to take, and whether worthwhile projects receive funding. When language and social norms heighten debt stigma, borrowing slows, transactions stall, and the circulation of money decreases. Conversely, when language reduces stigma, borrowing increases, spending accelerates, and the velocity of money can rise—along with the risk of speculative bubbles. The key policy question isn't whether debt stigma exists; that's clear. The real question is how to adjust it, sector by sector, to harness its potential without triggering the next bubble.

Debt stigma and the speed of the economy

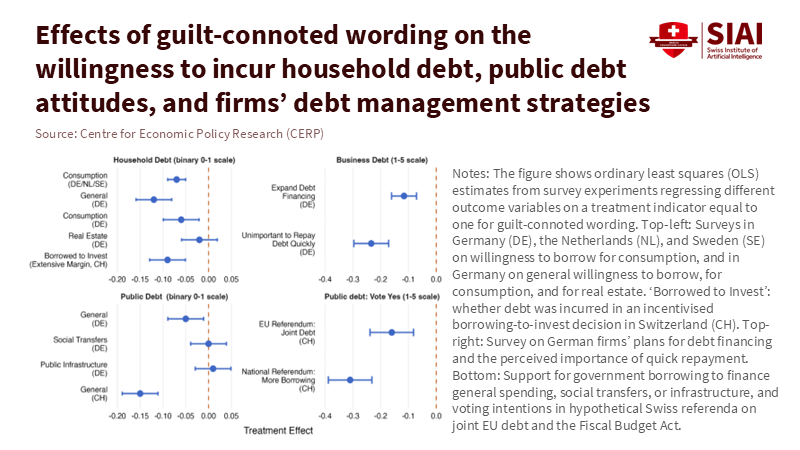

The way we talk influences the willingness to borrow. Recent experiments show that when borrowing is framed in terms that evoke guilt or moral failings, people tend to withdraw, even from profitable opportunities. In a prominent 2024 study, a third of participants prioritized paying off small debts over a higher-return investment, and their likelihood of borrowing for investment dropped by nearly half when it was framed as "being in debt." These behavioral barriers aren't just theoretical; they hinder real economic activity by delaying purchases and investments. They also interact with the monetary base: when individuals and companies hesitate to borrow or spend, each euro or dollar results in fewer transactions. In the United States, the velocity of M2 remains significantly below its average before 2008, indicating low spending despite an increase in nominal money balances. The way we discuss financial obligations should be considered among the factors that affect economic activity.

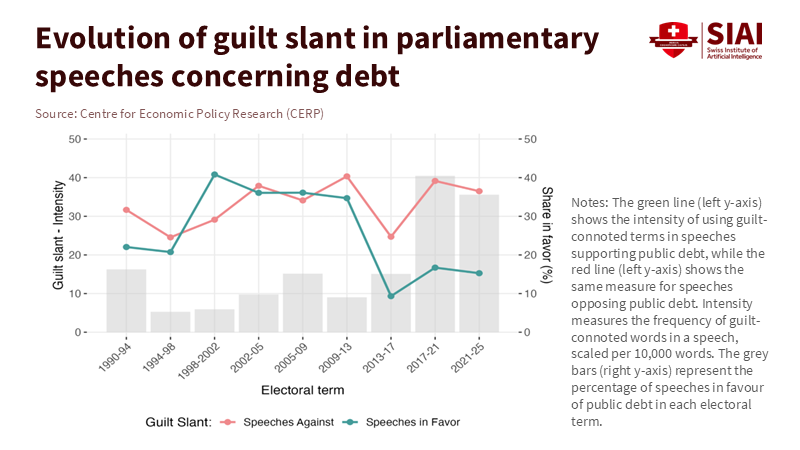

Debt stigma also explains why the term "installments" seems more straightforward than "debt." A 2024 study on Buy-Now-Pay-Later programs found that presenting the same price as a series of smaller payments led to more purchases and larger baskets. The reasoning is straightforward: installments feel like manageable budgeting instead of an acknowledgment of debt. Changing the way we frame these situations can make a big difference in spending. This pattern holds for public finance as well: support for government borrowing declines when debt is presented in guilt-ridden terms but increases when the focus is on tangible, productive purposes. In essence, the same infrastructure project can gain votes when labeled an "investment," but lose them when labeled a "debt." A central bank can't control the language, but ministries, regulators, universities, and lenders can—and they should see debt stigma as a tool to influence.

Debt stigma as a tool of policy communication

If the language impacts borrowing, then the terms used in policy and finance offices matter. Student loan programs that emphasize repayment safety, income-based protections, and purpose—rather than guilt—tend to see higher enrollment in sensible repayment plans. Previous research on repayment framing confirms this, showing that the choice of words can shift preferences and uptake by changing the psychological weight of obligations. During tight fiscal periods, these adjustments can be low-cost yet impactful: from using "plan selection" instead of "debt repayment" in communications to online portals that default to installment framing and mention risk safeguards before showing balances. Regulators face a similar challenge. Mixing moral language with warnings in consumer credit disclosures can backfire, increasing feelings of shame and discouraging individuals from seeking help early. Evidence from the UK's Financial Lives and mental health studies supports this: stigma keeps people from contacting lenders and worsens outcomes. A disclosure that alleviates fear can enhance both borrower well-being and lender recovery rates.

Debt stigma should also be part of the conversation about monetary policy. Language about credit conditions often uses cautionary metaphors like "addiction," "discipline," or "belt-tightening." Such terms may serve a purpose during economic booms. However, during periods of deleveraging, they can imply moral judgment and slow the return to healthy risk-taking. Central banks monitor money velocity, credit growth, and stress indicators; they may also consider tracking a qualitative "stigma index" based on speeches, advertising, and media coverage. When velocity drops and productive investment is weak, finance ministries and educational agencies should shift to language that focuses on investments with clear social purposes, risk-sharing features, and automatic safeguards. The goal isn't to encourage excessive borrowing but to ease unnecessary fear around responsible leverage. When the objectives are clear—like skills, research, and infrastructure—support for borrowing increases. Shifting from shame to purpose is a valid tool alongside interest rates and macroprudential regulations.

Debt stigma, corporate finance, and the pecking order

Corporate treasurers have long adhered to a pecking order: use internal funds first, turn to debt second, and rely on equity as a last resort. Family-owned businesses tend to be even more cautious about outside financing, aiming to retain control and preserve their legacy. This conservative approach helps companies endure challenges, but it can also limit high-return projects when retained earnings fall short. Behavioral evidence suggests part of this caution stems from debt stigma within the company, not just financial calculations. Experiments show that managers, like households, are reluctant to take on beneficial loans when guilt-laden language is used. This creates a hidden tax on investment that can stifle job creation and productivity. For small and medium-sized businesses supplying schools and universities—such as ed-tech companies and apprenticeship providers—the distinction between "installment financing for growth" and "taking on debt" can determine whether they hire more staff or delay hiring. Finance ministries offering guarantees should use language that emphasizes purpose, repayment paths, and safety nets, rather than moral hazards.

The same reasoning applies to college campuses, research units, and spinouts. Universities that rely solely on internal funding until they run out may lose opportunities to expand promising labs or degree programs. Effectively framed credit lines that align with grant cycles, include revenue thresholds, and are described in straightforward, non-judgmental terms can help departments manage cash flow without stigmatizing responsible borrowing. Framing also plays a role for students considering investing in short, high-return credentials. When loan offers emphasize shame or "debt loads," acceptance rates decline; however, when they highlight repayment limits, income-contingency, and potential earnings, interest tends to increase. The evidence is clear: fear of debt has real costs, and framing payments as manageable can improve adoption. The policy goal isn't to eliminate caution but to direct it. In productive areas—such as STEM apprenticeships, nursing programs, and research infrastructure—we should work to reduce debt stigma to foster growth. In situations with high consumption risk or predatory practices, we should maintain some friction.

Guardrails: curbing bubbles while reducing debt stigma

Reducing debt stigma will increase borrowing slightly. That's the intention—and the risk involved. History shows that prolonged periods of easy credit and rapid lending growth tend to precede banking crises. The global policy toolbox already has guardrails prepared for this situation. The credit-to-GDP gap serves as a reliable early-warning signal; when it expands, authorities can raise countercyclical capital buffers, tighten loan-to-income limits, or adjust sector-specific risk weights. The relationship between lenient policies and future instability has been documented over decades. When policies remain lax for too long, the likelihood of a crisis increases. Suppose we decide to normalize language to reduce shame around responsible borrowing. In that case, macroprudential tools must be activated and prepared for use. This embodies the bargain—reduce stigma where it hampers good projects, while tightening safeguards before speculation rises.

For education and local government, this bargain is practical. University CFOs can commit to stress tests that trigger spending pauses if debt-service ratios exceed thresholds. Student aid agencies can use "purpose-oriented" language while incorporating automatic stabilizers, such as payment holidays tied to unemployment rates. Regulators can encourage lenders to replace shameful wording in hardship letters with clear options and time-bound plans, as evidence suggests this approach leads to better engagement and contact rates. Finance ministries can adopt a standing language protocol: during downturns, use terms like "investment" and "income-contingent safeguards," and during upswings, emphasize "limits," "buffers," and "cooling measures." This creates a communication cycle that works in tandem with financial cycles, treating debt stigma as a variable to adjust rather than an unchangeable fate. If managed correctly, we can facilitate faster transactions without creating chaos.

We can trace a clear path from this initial insight to an actionable plan. Debt stigma harms individuals and slows the economy. It discourages sensible borrowing, suppresses valuable risk-taking, and keeps money idle in accounts instead of circulating in classrooms, labs, and productive businesses. Altering the way we communicate can change that equation. Experiments, retail evidence, and survey data suggest that how we frame debt can encourage the use of sensible credit without sacrificing caution, especially when the purpose is clear and safeguards are evident. Policymakers and educators should leverage this now. Universities should redesign financial aid and research communication to focus on purpose and protection. Regulators should replace shameful language with constructive solutions in hardship letters. Ministries should view communication as an additional tool alongside interest rates and buffers. Central banks should monitor stigma as closely as they track velocity. Reduce debt stigma where it helps develop human capital; use early-warning tools to support the system. If we can do both, we can achieve faster growth without losing stability.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aksoy, C. G., Dolls, M., Klejdysz, J., Peichl, A., & Windsteiger, L. (2025). Speaking of Debt: Framing, Guilt, and Economic Choices. CESifo Working Paper No. 12060. SSRN.

Bank for International Settlements. (n.d.). Credit-to-GDP gaps—overview. BIS Data Portal.

Drehmann, M., Borio, C., & Tsatsaronis, K. (2013). Total credit as an early warning indicator for systemic banking crises. BIS Quarterly Review.

Financial Conduct Authority. (2025). Financial Lives 2024 Survey: Key findings (May 2024 fieldwork). FCA.

Martínez-Marquina, A., & Shi, M. (2024). The Opportunity Cost of Debt Aversion. American Economic Review, 114(4), 1140–1172.

Maesen, S., & Ang, D. (2024). Buy Now Pay Later: Impact of Installment Payments on Customer Purchases. Journal of Marketing. Author-accepted manuscript.

Money and Mental Health Policy Institute. (2023). Debts and Despair. London.

San Francisco Fed (Ò. Jordà). (2023). The historical effects of banking distress on economic activity (summary page). Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Current Policy Perspectives.

St. Louis Fed. (2025). Velocity of M2 Money Stock (M2V). FRED series.