Confusopoly Pricing Is a Feature, Not a Bug

Input

Modified

Firms use complexity to hide true costs UK evidence shows obfuscation raises prices even with competition Standard total-price labels, algorithm-aware enforcement, and price literacy can protect consumers

In the United Kingdom, regulators estimate that hidden fees cost consumers around £2.2 billion a year until a ban took effect in April 2025. This amount is not unusual; it represents just the visible part of a larger issue in markets where companies benefit from making prices hard to compare. This is confusopoly pricing. It includes menus that split a single price into multiple charges, contracts with changing tariffs, and bundles that mix quality and quantity, leaving the cheapest option unclear. We have seen this as a nuisance, but it is a strategy that can raise average prices even when competition gets tougher. The experience from the UK smartphone market between 2010 and 2012, along with today's online checkouts, shows the same lesson: opacity benefits sellers. Regulators are responding with bans on unexpected price increases mid-contract and hidden fees online. However, enforcement will only succeed if education systems, employers, and service providers change how people learn to deal with price complexity.

From phone shops to checkout screens: how confusopoly pricing works

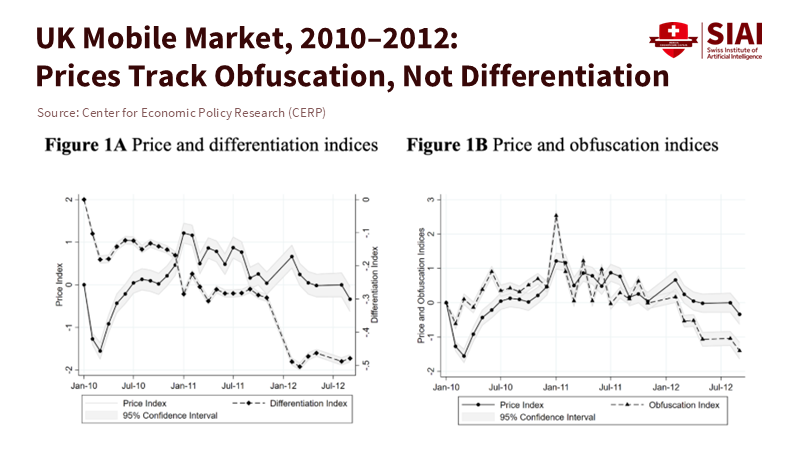

Confusopoly pricing takes advantage of the difference between what buyers believe they are comparing and what actually affects the bill. In smartphone contracts, that difference used to get lost in details like handset subsidies, data caps, minutes, text allowances, extra charges, and early termination fees. Operators pushed "dominated" plans—those that offered worse deals than others—to fill the market and dampen price competition. When every plan seemed special, buyers struggled to spot the few that were poor choices. The outcome in the UK from 2010 to 2012 was surprising: as menus became busier and more overlapping, average prices rose. This pattern is shown in the LSE analysis of UK mobile tariffs, which tracked nearly all offers during that time and found that increases in plan options and their dominance led to higher prices, even as portfolios converged. This mechanism is now common in the online world, where many options, fine print, and last-minute fees exist. This setup encourages consumers to choose quickly rather than wisely.

Research explains why this can be profitable, even when more sellers enter the market. When a market has a mix of savvy and less informed buyers, more competition doesn't always lead to lower prices. Companies can divide the market: some chase informed customers, while others profit from those confused by complicated menus and unnecessary differences. Experiments by Kenan Kalaycı show that sellers use complexity to increase buyer mistakes and that prices can be higher in markets where creating confusion is easier. In practice, this means extra fees, information overload, and split pricing—strategies that work well in digital checkout processes. Add mobile screens and fast decision-making, and the advantage grows even more. Complexity does not just represent product variety; it is a way to reduce price pressure.

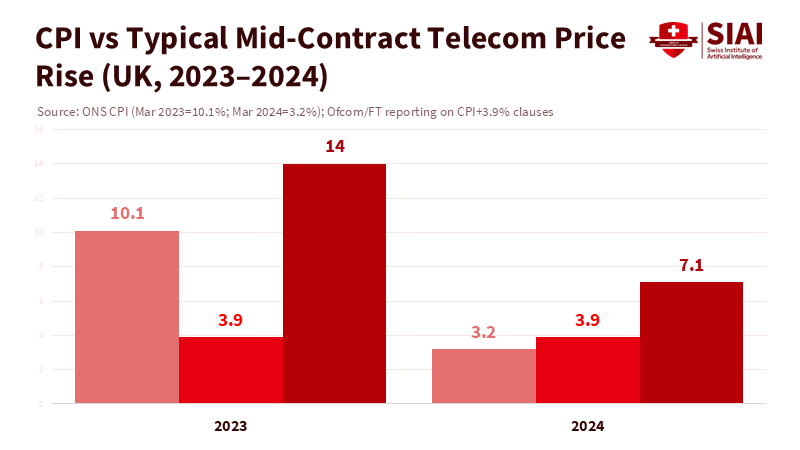

Confusopoly pricing and the UK's recent rule reset

Over the past two years, the UK has worked to limit the most harmful types of confusopoly pricing. Starting January 17, 2025, phone, broadband, and pay-TV providers can no longer add inflation-linked or percentage-based price increases to new contracts. Any future growth must be stated clearly in pounds and pence. This change follows two years of CPI+3.9% clauses, which pushed mid-term hikes into double-digit percentages during the inflation spike. At the same time, the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024 (DMCC) took effect on April 6, 2025. This act, the result of regulators' and policymakers' work, bans "drip pricing"—the practice of adding mandatory fees late in the checkout process—and strengthens enforcement against unfair practices, including fake reviews. Together, these measures, driven by regulators and policymakers, address issues at both the contract stage (telecoms) and the checkout stage (e-commerce). However, neither ban eliminates complexity; it only reduces the most blatant practices. Companies still have reasons to design for confusion.

The harm caused by dark patterns is now widely acknowledged. The OECD's 2024–2025 work highlights how drip pricing, pre-selection, urgency prompts, and hard-to-cancel designs undermine trust and shift surplus. UK consumer groups estimate the hidden fees burden in the billions before the DMCC. New guidance from the Competition and Markets Authority clarifies that headline prices must include fixed mandatory charges and must disclose variable mandatory charges early and clearly. These improvements are significant but confirm the main point: complexity has been so widespread that it needs legal change. As we celebrate the reform, we must also recognize what it means. Confusopoly pricing is adaptable. Rules will pursue it. If policies only react, consumers will continue to lose ground.

Confusopoly pricing in insurance and employment contracts

The same tactics appear in areas beyond telecoms and online retail. Insurance has long been known for complex disclosures, add-on financing, and renewal pricing that clouds the real cost. UK regulators have focused on general insurance practices and premium financing, in which customers pay more to spread payments over time. The FCA's 2025 "Roadmap for retail insurance" outlines where complexity limits competition and where solutions—like equalizing renewal and new-business prices—can be effective. New 2024 data on value measures show how regulatory actions can change headline ratios in add-on products like GAP insurance, highlighting how product design and presentation affect value. Insurance pricing involves a lot of information, and buyers often treat it as an annual task. This makes them easy targets for confusopoly strategies, from dense fact sheets to optional extras presented as defaults.

The same approach even extends to job relationships. Research on "confusopoly in the 21st-century employment relationship" claims that unclear job terms—such as bonus schemes, scheduling expectations, and non-compete policies—can shift bargaining power and reduce adequate pay. The evidence is still developing and is less concrete than in telecoms. Still, the trend aligns with consumer markets: when important terms are scattered across handbooks, portals, and onboarding materials, employees misjudge the job. Some accept lower total value than they realize; others leave when hidden limitations become apparent. In both cases, complexity gives employers more time and options. This weakens competition in the labor market. As algorithmic management increases and task-based contracting rises, the risk grows that a lack of clarity will become the norm in HR.

What the UK smartphone episode taught us and how to prepare for it

Looking back to 2010–2012, UK operators settled on similar product portfolios while adding more tariffs and dominated plans. At the same time, smartphone use increased, and 3G data became a significant cost. Ofcom's market reports from 2011–2012 show the speed of product changes, the spread of bundles, and the growth of multi-service offers. Inside stores, the choice setup encouraged buyers to choose long-term contracts with subsidized handsets. Students and those with low incomes faced the most significant challenge: understanding effective prices across minutes, data caps, and excess fees took time and numerical skills that many lacked due to exams, jobs, or commutes. The LSE evidence reflects the real experience from that period: complicated menus helped sustain higher average prices. The past informs the present. Although today it involves checkout fees, premium finance, and subscriptions, the methods remain similar. Educators should view this as a literacy issue, not just a shopping skill.

We need to teach confusopoly pricing directly in secondary education, vocational programs, and university orientations. Start with three habits. First, reduce any offer to a unit price you can compare: the total cost over the contract term divided by the quantity (months, gigabytes, kilometers, kilowatt-hours). Second, spot-dominated options: if Plan B is worse than Plan A in every relevant aspect, eliminate it quickly. Third, check the option partitions: add-ons, fees, and financing should be combined into a single total before making a decision. These are not complex techniques; they are basic retail arithmetic that complexity aims to confuse. If institutions do not teach these skills, a ban on one practice will merely shift confusion elsewhere.

Policy and practice: turning bans into better choices

Bans on inflation-linked mid-term increases and drip pricing create a new baseline. The next step is to realize transparency. Regulators should require a standard comparison label for contracts with recurring payments—such as telecoms, insurance, energy, and transport subscriptions. If a product has multiple price components, the main price must display a single "Total Effective Monthly Price" calculated consistently over the contract duration. Companies already do this internally; the rule would ensure a consistent presentation. Competition can then focus on what customers can see easily. The CMA's 2025 guidance on total prices is a starting point; it should grow into a cross-sector standard with real-time audits and penalties for non-compliance.

Enforcement should also consider algorithms. Confusopoly pricing increasingly operates in the code that organizes checkout processes and renewal prompts. Auditors need access to user-journey data that tracks which fees appear when, which defaults are selected, and how many clicks it takes to find cancel links. Regulators can learn from accessibility standards: test flows with panels, publish failure rates, and demand quick fixes for issues. Where personalized pricing uses machine learning to segment customers by price sensitivity, regulators should require impact assessments to determine whether complexity is aimed at the least informed. Recent legal research has explored algorithmic price personalization and its risks; these tools should be part of consumer protection, not just competition cases.

Education providers also have a crucial role. Universities and colleges can present their own student-facing contracts (such as accommodation, meal plans, transport, and software subscriptions) in clear formats. They should provide a standardized unit-cost table at the point of choice. Annual "financial literacy labs" should be part of induction week, using real case studies on telecoms and insurance pricing. Partnerships with local regulators can lead to micro-credentials that certify students in "Choice Architecture Literacy"—a skill valued by employers and useful in daily life. Publishing companies and MOOC platforms can include confusopoly modules in economics, law, and design courses. The goal is not to make everyone a regulator. It is to equip the average buyer with the knowledge to navigate complexity effectively.

Employers should also improve their practices. Job ads and contracts must include total compensation calculators that display base pay, predictable bonuses, and likely schedule costs on a single screen. Changes to performance policies should be tracked and documented with the same care as software updates. If a policy is too complicated to fit on a page, assume candidates and staff will misprice the job. This leads to turnover, complaints, and hidden pay cuts. Transparency here is not a favor; it is a way to hire and retain talent without unexpected costs.

Anticipating the critiques

Critics might argue that complexity often arises from genuine variety. That's partly true. Markets with diverse preferences need a range of options. But diversity does not require bad options or late fees. The LSE data from the UK mobile market indicates that as dominant tariffs increased, average prices also rose; this is a strategy, not just variety. Experimental research also demonstrates that sellers can benefit from confusing menus, even with more competitors. Another critique is that constant rule changes can stifle innovation. However, the UK's mid-contract rule does not limit price changes; it demands clarity upfront in monetary terms. The DMCC does not eliminate optional extras; it insists on transparency for mandatory ones. These regulations target confusion, not choice. If innovation relies on buyer confusion, it isn't worth preserving.

A final critique concerns regulatory expansion and enforcement costs. Here, standardization offers a solution. A cross-sector "Total Effective Monthly Price" label encourages private enforcement through comparison platforms and consumer advocacy groups. It simplifies audits: either the price includes all mandatory elements or it does not. Evidence from other consumer protection systems shows that more transparent labels reduce complaints and lawsuits over time. And where backsliding is seen—like in sectors that continually invent new price structures—the rules can adjust. Complexity is constantly changing; a standard gives regulators a fixed target.

The £2.2 billion estimate for hidden fees wasn't only about airline seats or delivery charges. It reflected a market design where confusion is not a mistake but a feature. The UK's 2025 reset, which eliminates inflation-linked mid-contract hikes and mandatory fees, shows that laws can make a difference. However, rules alone won't create clarity. We will only overcome confusing pricing when schools, colleges, and employers teach people to simplify complex menus into a single, clear comparison, and when companies are required to publish that number by default. The smartphone issue from a decade ago demonstrated how quickly unclear pricing can increase costs when options multiply. Today's checkout screens are quicker and more personalized, which raises the stakes. The way forward is straightforward, though not necessarily easy: one standard price, one set of precise terms, and one public record of changes. If we make these the norms we teach and enforce, confusion will lose its power and profits will increase.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Barros, L., et al. (2023). The rise of dark patterns: does competition law make it any better? Cambridge Law Journal.

Centre for Economic Performance, LSE. (2022). in brief… Confusopoly: how mobile phone companies use product complexity to raise prices.

Genakos, C., Kretschmer, T., & Nicolle, A. (2021). Strategic confusopoly: evidence from the UK mobile market (CEP DP 1810). London School of Economics.

Government of the United Kingdom. (2025). Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024 (commencement April 6, 2025).

Kalaycı, K. (2016). Confusopoly: competition and obfuscation in markets. Experimental Economics, 19(2), 299–316.

Kalaycı, K. (2015). Confusopoly: competition and obfuscation in markets (working paper PDF).

LSE Business Review. (2021). When oligopolies confuse consumers, beware the rise of confusopoly.

OECD. (2024–2025). Dark commercial patterns (topic brief and blog).

Ofcom. (2011, 2012). Communications Market Reports (UK).

Ofcom. (2024). Ban on inflation-linked mid-contract price rises (effective January 17, 2025).

UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). (2025). Unfair commercial practices: guidance (CMA207) and news on DMCC commencement (drip-pricing ban, fake reviews).

Which? (2023). Stung by fees: How consumers are harmed by drip pricing (policy report).