Weak Dollar Risk: Three Shock Channels That Hit Emerging Economies First

Input

Modified

A weak dollar is a systemic risk for non-key currency economies Losses hit reserves, balance sheets, and trade through dollar pricing Diversify reserves, match contract and debt currencies, and build hedging

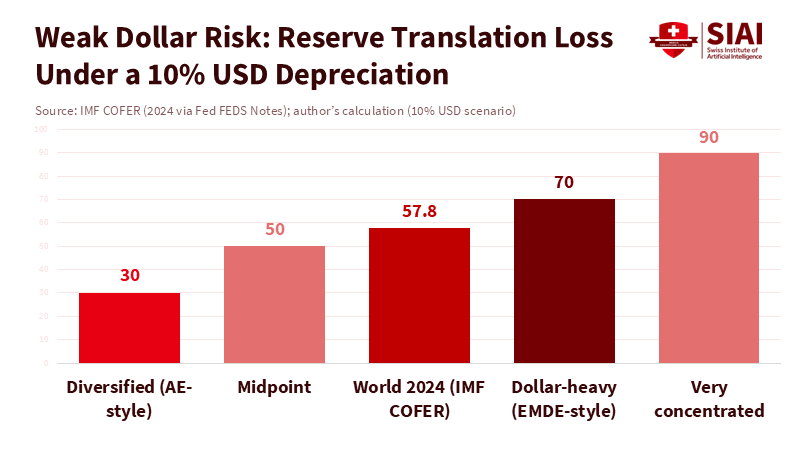

One fact stands out. In 2024, the U.S. dollar made up about 58% of the world’s known foreign-exchange reserves. This figure dwarfs the euro at around 20% and leaves other currencies in the single digits. If the dollar drops by 10% against a country's home currency, the value of its dollar-denominated reserves decreases correspondingly in domestic terms. For a central bank with a significant dollar portfolio, this translates to a sudden paper loss of about 5% of reserves. In many emerging economies, the dollar share is well above half; these losses hit hardest when policymakers most need a financial cushion. The issue isn't that a weak dollar always causes problems. It's that weak dollar risk is a structural reality embedded in the balance sheets and trade contracts of many nations outside of key currencies. When the dollar changes, everything else follows suit.

Why “weak dollar risk” is not a free lunch

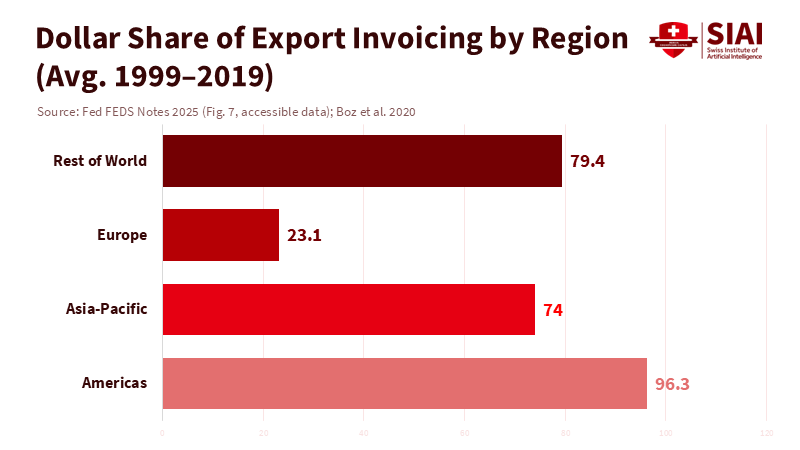

Many believe that a weaker dollar benefits emerging economies. Debt servicing is easier for those who owe in dollars, and local markets might see a return of capital. This perspective has some truth in the short term, but it overlooks a more profound vulnerability. Most emerging economies continue to save, borrow, and invoice trade in currencies they don't issue, particularly the dollar. A weak dollar can diminish the domestic value of reserves, disrupt hedges, and alter prices for exporters overnight. New studies indicate that the dollar’s significance isn't fading quickly. The Federal Reserve’s 2025 forecast shows the dollar will remain near 58% of global reserves, with dollar invoicing still prevailing outside of Europe. Thus, weak dollar risk is a systemic issue, not just a temporary one. It should be seen as a structural challenge to manage rather than a windfall to exploit.

Today, central-bank analysis typically takes a nuanced approach. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) finds that a weak dollar can sometimes support emerging markets through the financial channel because funding costs decline in local currency terms. However, the same BIS research warns that the trade channel can negatively impact countries dependent on U.S. demand. Balance-sheet effects and supply-chain credit risks can lead to unpredictable shocks along firm networks. The result is not simply a gain or a loss; it forms a complex interaction that relies on a nation's reserve structure, debt makeup, and export markets. Policymakers and educators should highlight this tension as essential economic literacy.

Channel 1: Reserves, buffers, and the weak dollar risk translation loss

Let’s start with policy buffers. Reserves serve as insurance against external shocks. Globally, the dollar still underpins these reserves. When the dollar weakens against a central bank’s reporting currency, the domestic value of its dollar assets also falls. If half the reserve portfolio is in dollars, a 10% drop in the dollar value means about a 5% loss in reserves when viewed in local currency. Countries with larger dollar stakes suffer even more. This is not trivial; it reduces the financial power that finance ministries count on to stabilize markets and manage capital outflows. It can also complicate rules that limit losses or tie transfers to the treasury, tightening budgets during downturns. IMF COFER updates through 2025 highlight the dollar's significant and persistent share, despite quarterly fluctuations from exchange-rate changes. That’s why valuation shifts matter, especially when they coincide with other stresses.

The regional pattern heightens the risk of a weak dollar. Reserve managers in advanced economies often diversify effectively. In contrast, many emerging and developing countries still hold a higher percentage of their reserves in dollars. Academic research using new country-level data reveals strong regional clustering and continued dollar dominance in emerging market portfolios. Simply put, countries most likely to experience sudden-stop dynamics are also those at risk of translation losses when the dollar declines. Even when authorities do not disclose specific compositions, BIS and ECB analyses reach the same conclusion: the currency in which reserves are held directly affects resilience. This knowledge should be shared not only in central-bank boardrooms but also in classrooms, training the next generation of public-sector economists. They need to learn how to assess and stress-test reserve portfolios during weak dollar situations, not just intense dollar periods.

Channel 2: Balance sheets, hedging costs, and weak dollar risk inside firms

The second channel involves corporate and sovereign balance sheets. Much of the external debt that emerging market borrowers issue still comes in dollars. By early 2025, the IMF’s issuance monitor showed that just under 70% of new emerging-market international bonds were dollar-denominated. When the dollar weakens, the debt service in local currency for that stock decreases. This can improve cash flow, narrow credit spreads, and potentially support investment—up to a point. However, many companies hedge their dollar exposure through derivatives or natural hedges in trade. A sudden drop in the dollar can create mark-to-market losses on hedges or misalign hedges with revenues priced in dollars. The BIS illustrates how exchange-rate shocks ripple through trade-credit chains, exposing smaller suppliers to risks stemming from the balance sheets of larger firms that owe in foreign currency. Weak dollar risk is not confined; it spreads throughout supply networks.

Recent research from the BIS sharpens this focus. Rather than just looking at trade-weighted exchange rates, researchers are developing firm-specific measures that track the currencies in which companies invoice and receive payments. These measures explain profitability more accurately than generic currency baskets, especially for smaller exporters. They also reveal that financial hedging only partially offsets currency fluctuations. Simply put: the currency of contracts is as crucial as the currency of debt. A weak dollar may ease immediate debt burdens but could still harm margins if sales or inputs are repriced in ways the hedge does not cover. Finance directors should test both sides together. MBA programs should include invoice currency mapping in standard hedging courses, and policy schools should do the same for sovereign debt management.

Channel 3: Trade invoicing, capital flows, and weak dollar risk in the real economy

The third channel combines trade pricing with capital flows. Outside Europe, most global trade is billed in dollars, regardless of the trading parties involved. The Federal Reserve’s 2025 review states that the dollar represents about three-quarters of invoicing in the Asia-Pacific region and nearly 80% globally, with Europe as the exception where the euro prevails. In this setup, a weaker dollar can lower the local-currency cost of dollar-priced imports and inputs, which should be beneficial. However, it also limits price competitiveness for U.S. exporters whose currencies appreciate alongside the dollar’s decline. Research on dominant-currency pricing shows that shifts in the dollar often predict global trade volumes. A weaker dollar generally boosts trade, but the effects vary by region, product type, and dependency on U.S. customers. Hence, weak dollar risk is asymmetric: some exporters see increased volumes while others experience decreased margins.

Capital flows respond as well. The BIS indicates that local-currency bond and equity flows to emerging market economies are more sensitive to the dollar’s movements than to interest rate differences, and this sensitivity has grown since the mid-2010s. Inflows typically return when the dollar weakens; this is one reason asset managers claim that emerging markets perform better in weak-dollar periods. AllianceBernstein underscored this argument in mid-2025, drawing on historical data and market positioning. The nuance is that flows tend to follow trends and can shift quickly. Countries with shallow markets or limited export bases may face inflows that challenge regulatory measures. Educators and regulators should highlight these connections: trade invoicing determines relative prices; dollar fluctuations direct capital flows; and the interplay can amplify both booms and busts. Weak dollar risk is not solely an exchange rate issue; it also involves market structure.

What the newest evidence implies for policy design

The latest BIS Bulletin (No. 114) serves as a helpful reference. It illustrates that a weaker dollar can stimulate emerging economies with two characteristics: low dependence on U.S. goods demand and a high percentage of short-term foreign-currency debt, which becomes cheaper in local currency. This applies to a portion of emerging markets. Others may face challenges in countering trade losses through supplier credit, which diminishes financial benefits. The policy takeaway is not to bank on a weak dollar; it's to neutralize weak dollar risk. This begins with a reserve strategy. Where information allows, shift toward a more diversified currency mix and stress-test the reserve portfolio for potential dollar declines, not just increases. Where information is limited, establish internal guidelines to limit concentration and tie rebalancing to clear standards, like COFER-style benchmarks adjusted for trade invoicing trends.

Next, address the structural issues that transform currency changes into credit pressure. Limit excessive dollar borrowing by firms that lack hedges. Promote the use of invoice currencies that align with revenue sources. Create swap lines and regional pooling arrangements to support dollar market stability without forcing the sell-off of reserves during downturns. For regions near Europe and Asia’s trade hubs, enhancing local-currency market-making and increasing hedging capabilities would initially lessen the need for high dollar holdings. Lastly, prioritize learning. Public finance institutes and business schools should offer case studies on dollar cycles that weave together reserves, debt management, invoicing, and capital-flow control. The goal is simple: reduce unexpected challenges, whether the dollar falls or rises.

Implications for educators and administrators

Curriculum developers in economics and public policy programs should treat weak dollar risk as an essential topic in international finance. Students should practice interpreting COFER tables, BIS flow data, and central bank balance-sheet notes, then conduct scenario analysis for weak dollar situations. Executive education programs for CFOs and treasurers should include “invoice-currency mapping” in standard hedging courses, focusing on how to synchronize debt currency, contract currency, and revenue currency. Education ministries and state treasuries can work with universities to design applied capstone projects for stress testing reserves and managing sovereign debt. These initiatives will cultivate a talent pool ready to handle currency fluctuations in real time rather than react after the fact.

Some argue that a weaker dollar is generally beneficial for emerging market assets, pointing to historical instances when emerging market equities and local bonds surged during dollar declines. The overall data support this trend. However, this aggregation overlooks underlying vulnerabilities. Countries heavily reliant on the U.S. market or with low liquidity can see trade and flow dynamics counterbalance any financial advantages. Others note that the dollar's share of reserves is steadily decreasing. This is true, but the decline has been gradual and inconsistent; when factoring in exchange-rate changes, the share remains broadly stable. Some contend that the invoicing landscape is beginning to fragment and that regional currencies will take on a larger share of trade pricing. While there may be shifts occurring, the dollar continues to dominate beyond Europe. Policymakers should act based on the current landscape, not on a hopeful future market.

A final word on measurement

Think of weak dollar risk as a collection of indicators, not a single measure. One dial shows the valuation losses on reserves when the dollar declines. A second track balances the impact on firms' and sovereigns' balance sheets, which can either positively or negatively affect them based on hedges and invoice currencies. A third track monitors trade volumes and capital flows, which respond to dominant-currency pricing and global risk sentiment. BIS research and IMF data enable us to quantify each of these indicators. The task for ministries, central banks, and universities is to connect these indicators into policy guidelines that prompt hedging, rebalancing, and communication before markets necessitate action.

Conclusion. The opening fact still stands: the dollar anchors official reserves and global contracts. That is why the risk of a weak dollar is real. When the dollar falls, central banks with large dollar portfolios experience translation losses while market stress rises. Firms benefit from dollar debts but may face difficulties with poorly matched hedges and invoices. Exporters to the United States encounter tougher price competition, even as global trade volumes may increase. Evidence from BIS, the IMF, and the Fed provides one clear lesson. We should not base our policy on the dollar’s trend. We need to create systems that are safe regardless of how they change. This means having diversified reserves, matched currency structures, deeper local hedging markets, and an education program that views the dollar cycle as a fundamental issue. If we implement this plan now, the next period of dollar weakness will be manageable, rather than a crisis waiting to happen.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AllianceBernstein (2025). Would a Weaker U.S. Dollar Support Emerging Market Assets? May 14, 2025.

Bank for International Settlements (2024). The U.S. dollar and capital flows to EMEs. BIS Quarterly Review, September 2024.

Bank for International Settlements (2025). A Weaker U.S. Dollar Can Entail Both Tailwinds and Headwinds for EMEs. BIS Bulletin No. 114, October 2025.

Bertaut, C., et al. (2025). The International Role of the U.S. Dollar — 2025 Edition. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (FEDS Notes), July 18, 2025.

Dainauskas, J. (2023). Time-varying exchange rate pass-through into terms of trade. Journal of International Money and Finance.

IMF (2025). COFER: Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves—Latest Updates and Blog Posts. October 1, 2025; April 1, 2025.

IMF (2025). EM and Frontier Markets Bond Issuance Monitor (January 2025).

Juselius, M., et al. (2025). Financial channel implications of a weaker dollar for EMEs. BIS Bulletin No. 114.

Nookhwun, N., et al. (2025). Exchange Rate Effects on Firm Performance: A NICER Measure. BIS Working Paper No. 1266.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2024). Trade Invoicing Currency Information in the Import and Export Price Indexes. August 28, 2024.