Nepal Youth Protests and the BRI: How Street Anger Reshapes Beijing’s Neighborhood Policy

Input

Modified

Gen-Z protests toppled Nepal’s pro-China leader Beijing now protects projects, not personalities Fixes: transparent deals, quick jobs, civic-skills education

Seventy-four dead in three weeks is significant. It is a generational verdict. In September 2025, streets across Nepal were filled with young people after the government blocked major social platforms and ignored ongoing anger over corruption and limited job opportunities. Nineteen people died on the first day alone. Within forty-eight hours, Prime Minister K. P. Sharma Oli resigned as curfews were imposed and soldiers took control of central Kathmandu. By the end of that week, former chief justice Sushila Karki was sworn in as interim prime minister, becoming the first woman to lead the country. Viewed globally, the Nepal youth protests appeared to be a response to an ineffective ban; seen locally, they were a confrontation with a political class that treated consent as negotiable. The region took notice, including Beijing. China’s initial reaction was cautious rather than defensive of an ally. This indicated that the Belt and Road Initiative is entering a phase where political risk is assessed not only in capitals but also on the streets. That’s why a domestic uprising in Kathmandu matters from Colombo to Gwadar.

Nepal youth protests reframed as a geopolitical pivot

From a distance, the footage looked straightforward: students in helmets, police with batons, and flames near parliament. Up close, the Nepal youth protests revealed the cost of supporting a leader who had lost local consent. The ban on Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, and X was lifted within a day, but the damage was done. Reliable counts rose from nineteen dead to over seventy within two weeks, with thousands injured. Soldiers patrolled the capital under a sweeping curfew. Flights came to a halt, and Kathmandu remained tense as the army secured essential sites. Beijing’s early public messages avoided specific individuals and emphasized stability. Soon after the leadership change, the Chinese Foreign Ministry congratulated the interim leader. It highlighted respect for Nepal’s “independent choice,” noting continuity with the state rather than loyalty to any particular politician.

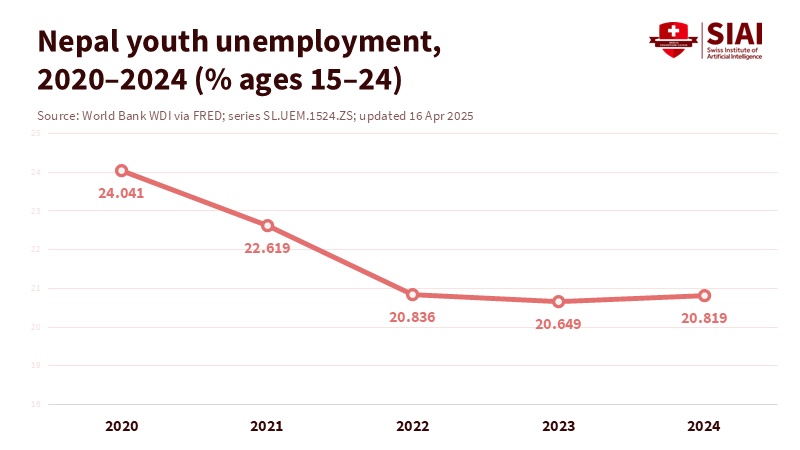

Nepal’s economic situation made the spark more volatile. Youth unemployment sat at around 20.8 percent in 2024. Personal remittances accounted for roughly 27 percent of GDP in 2023. By mid-2025, inflation eased toward the 2.7 to 2.8 percent range, yet that relief felt abstract when first jobs were hard to find, either locally or abroad. The World Bank’s April 2025 update pointed out a current-account surplus earlier in the fiscal year and sufficient reserves. Still, it cautioned that remittance growth would slow as migration decreased. In short, households appeared stable on paper even as young people felt stuck in reality. This made the sudden attempt to shut down social media seem like an attack on daily life and freedom of expression.

One more shift deserves attention. China did not rush to defend its preferred partner—official statements called on “all sections” in Nepal to restore order. After the leadership transition, Beijing congratulated the interim government while invoking a long-standing friendship. That wording was intentional; it indicated a shift from focusing on individuals to maintaining continuity with the Nepali state. For countries involved with the Belt and Road, the message is clear: Beijing will engage whoever can stabilize the situation at home and protect its projects, even if that means moving past a once-reliable ally. This recalibration explains why the Nepal youth protests are a regional narrative, not just a local issue.

Sri Lanka’s experience clarifies Beijing’s next move

To understand what may happen next, look to Sri Lanka. After defaulting and experiencing mass unrest, voters chose Anura Kumara Dissanayake in late 2024. Many expected a downturn in Beijing’s support. Instead, the new leader sought “maximum support” from China for investment, tourism, and technology. By September 2025, Colombo had revived a long-stalled highway with a new US$500 million loan from China Exim Bank, even while restructuring efforts with other creditors and the IMF were underway. The pattern is familiar: when a friendly leader falls, Beijing hedges and collaborates with whoever holds power—protecting its assets and access while it rebuilds its influence.

Sri Lanka also serves as a warning and a guide. The 99-year lease of Hambantota port highlights the risks of debt-funded mega-projects. Yet even there, Chinese financial and political connections remained strong once a new balance was established. Beijing toned down its rhetoric, concentrated on deliverables, and re-engaged through projects and tourism instead of grand promises. The takeaway is not that the Belt and Road Initiative always succeeds, but that it adapts. For Nepal, this means policy discussions should focus on terms, openness, and pacing—because pulling back is unlikely, while renegotiation is very plausible.

This perspective applies to Nepal. Rather than lament the departure of a pro-China prime minister, Beijing shifted toward relationships that endure beyond leadership changes: regional ties, tourism flows, and project-by-project negotiations with whoever is in charge. Pokhara International Airport illustrates this point. The airport was built using a loan from China Exim Bank; in 2024, Kathmandu asked Beijing to convert that debt into a grant. The China-Nepal railway carries similar dynamics. A pre-feasibility study estimated that 98.5 percent of the route within Nepal would consist of tunnels or bridges. This cost structure requires unusual caution and consent. China’s messaging after the leadership transition—congratulating the interim leader and pledging to respect Nepal’s chosen path—suggests a practical shift: protect projects, reframe terms, and maintain friendly relations until a reliable partner emerges.

Context is important here. In December 2024, Nepal and China signed a cooperation framework to move long-discussed Belt and Road projects from ideas to plans. This agreement did not lock in financial terms. It sparked debate in Kathmandu about whether future projects should rely on grants, concessional loans, or public-private models. The upheaval of September 2025 will intensify that discussion. Suppose the interim government and its successor make contract terms public and phase in potentially risky projects. In that case, Beijing can still find a path to lasting cooperation, and Nepal maintains leverage based on transparency instead of secrecy.

Political risk now starts at home, not abroad

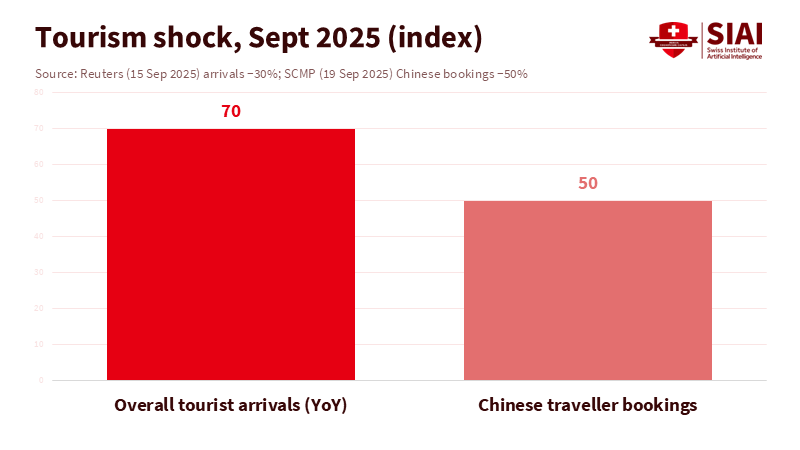

The protests did more than reset politics. They impacted the economy in real time. In mid-September, Chinese bookings to Nepal dropped by about half, with travel-market trackers predicting a 30 percent decline for the rest of 2025. Reuters reported a year-on-year 30 percent drop in arrivals during peak trekking weeks, as airlines suspended services and the airport closed due to curfews. Kathmandu hotels reported empty rooms. Tourism is a key employer and a source of foreign exchange. When it collapses, the effects are quickly felt in wages, imports, and tax revenues. Consequently, the Nepal youth protests carry costs beyond politics, a cost that leaders in other Belt and Road countries should take seriously.

The decline in tourism also highlights a fiscal impact. When occupancy in Kathmandu hotels hovers near 30 percent in a month that should see closer to 70 percent, payrolls shrink and tax revenues decline. Guides, porters, and small businesses suffer first and most severely. These costs rarely appear in bond prospectuses, but they influence public patience with large loans. Restoring confidence requires visible security, clear communication, and prompt, transparent repairs of damaged public assets—alongside honest updates on projects tied to foreign lenders.

However, macro balances offer a path forward. The World Bank’s April 2025 update indicated a current-account surplus earlier in the fiscal year and reserves at reasonable levels, even as growth slowed and migration decreased. Data from Nepal Rastra Bank show disinflation through mid-2025 and generally stable external accounts. Buffers can’t buy trust, but they can buy time. Use it wisely, and the recovery can focus on fast, local work that people can see. Use it poorly, and the next shock will hit harder. For outside lenders, the lesson is similar: political risk now begins at home, in whether citizens believe contracts are fair and jobs are viable.

What educators and policymakers should do next

A sustainable response must start in classrooms. Universities should incorporate civic skills into their core curriculum. Students should learn to read budgets, track procurement processes, and file information requests. They should gain an understanding of digital rights, shutdown methods, and safe organizing principles. This will reduce the social costs of protest by increasing the everyday price of corruption. The aim is not to stifle passion but to channel it. When graduates can follow the money, they can promote accountability through ongoing oversight instead of street confrontations. This could become the lasting institutional legacy of the Nepal youth protests—if educators embed it in their syllabi and assessments.

Ministries must also adapt. Treat consent as a crucial element rather than just a talking point. Publish the full terms of any significant loan before signing. Hold debates in parliament that include clear assessments of debt service and currency risk. Post independent audits online and keep them accessible. Create a pipeline of medium-sized projects—such as grid upgrades, road safety improvements, and river defenses—that can hire locals within months, not years. For large Belt and Road assets, insist on labor standards, local content, and genuine risk-sharing; if assets fall short, seek restructuring. China has already indicated a willingness to work with whoever governs in Kathmandu. This opens the door for tougher, more transparent agreements if Nepal’s future leaders choose to take it.

There is also room for new oversight. A practical step is a tripartite disclosure norm for any foreign-funded project above a specified threshold: the lender, the host ministry, and an independent auditor should release the same key terms simultaneously. Pair that with citizen dashboards that track construction milestones and jobs created. Such tools do not impede Chinese investment; they enhance its legitimacy. Beijing’s statements about respecting Nepal’s independent choices create space for this approach, and recent analysis shows it is already leaning toward institutional ties in Kathmandu rather than personal ones.

Anticipate the pushback. Some will argue that the Nepal youth protests were just a temporary outburst and that things will go back to normal. The prime minister’s resignation, the presence of the army, and the interim government suggest otherwise. Others claim that countries must either accept Chinese funding or manage without roads. That is a false dilemma. Terms can be made clear. Phases can be introduced gradually. Projects can be adjusted to match capacity. A final argument is that transparency slows growth. In reality, it builds trust—the most valuable resource—because citizens are more willing to endure disruption when they can see the contract.

The essential fact should not fade: seventy-four dead in three weeks. No government should test that number twice. The Nepal youth protests began over digital rights and evolved into a struggle for consent. They removed a leader, reshaped a regional narrative, and reminded outside powers that influence in South Asia now depends on the expectations of young people. The call to action is clear. Prioritize transparency. Tie funding to quick, local jobs. Phase in broader ambitions. Ensure every kilometer of “connectivity” also connects citizens to their government. If Nepal does this now, it will set a standard that even major powers must respect; if it does not, the next wave of dissatisfaction will come sooner and hit harder. This is the challenge facing Kathmandu today. It is also an opportunity to establish a higher regional standard.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera. “Who is Sushila Karki, Nepal’s new 73-year-old interim prime minister?” 17 Sept 2025.

Britannica. “2025 Nepalese Gen Z Protests.” 7 Oct 2025.

Chinese MFA (via UN Mission). “Spokesperson’s remarks on Nepal’s interim government.” 14 Sept 2025.

East Asia Forum. “China recalibrates in Nepal after Oli’s fall.” 21 Oct 2025.

Kathmandu Post. “Nepal asks China to turn Pokhara airport loan into grant.” 23 Aug 2024.

Kathmandu Post. “Oli preparing to visit China, may seek airport loan waiver.” 31 Oct 2024.

Kathmandu Post. “Nepal–China cross-border railway: 98.5 percent tunnels or bridges, pre-feasibility says.” 19 Mar 2022.

Nepal Rastra Bank. “Current Macroeconomic and Financial Situation (Ten Months 2024/25).” Jun 2025.

Nepal Rastra Bank. “Current Macroeconomic and Financial Situation (Annual 2024/25).” Aug 2025.

Reuters. “Nineteen killed in Nepal in ‘Gen Z’ protest over social media ban.” 8 Sept 2025.

Reuters. “Soldiers guard Nepal’s parliament after deadly protests.” 10 Sept 2025.

Reuters. “Former chief justice Karki named Nepal’s first female PM after violent unrest.” 12 Sept 2025.

Reuters. “Sri Lanka resumes key highway project with $500 million new Chinese funding.” 17 Sept 2025.

Reuters. “Nepal’s tourism hammered by protests; arrivals fall 30%.” 15 Sept 2025.

South China Morning Post. “Sri Lanka’s new leader to seek ‘maximum support’ from China.” 24 Sept 2024.

South China Morning Post. “Chinese tourism to Nepal plummets after protests.” 19 Sept 2025.

World Bank. “Nepal Development Update.” 3 Apr 2025.

World Bank (FRED). “Youth Unemployment Rate for Nepal — 2024.” Updated 16 Apr 2025.

World Bank Data. “Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) — Nepal.” 2023.