Undersea Cable Security Is Now Education Policy in Southeast Asia

Input

Modified

Undersea cable security is now core education infrastructure in Southeast Asia Taiwan’s 2025 cable disruptions show how gray-zone incidents can cut classes, exams, and research ASEAN must build redundancy and protect its seabed links

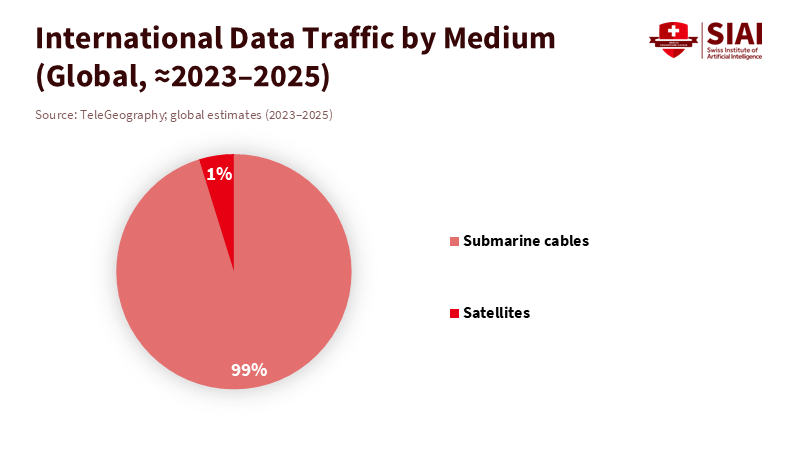

The number that should concern education leaders is between 95% and 99%. This is the share of international data that travels through fiber-optic cables on the seafloor, not satellites. These cables are essential for digital learning and research. When they fail, classes stop, labs lose data, and campuses go offline. Taiwan's experience in early 2025 demonstrated how fragile this lifeline is when politics and seamanship collide. Multiple cable cuts, a ship captain's conviction, and sharp denials from Beijing created a new pressure test that could disrupt any system relying on constant bandwidth, including education. In Southeast Asia, where learners depend on cloud platforms hosted in other countries, undersea cable security is not just a telecom issue. It is critical for ensuring teaching, exams, and scholarships across eleven countries and thousands of institutions. The seabed has become a vital utility for campuses.

Undersea Cable Security: The New Education Infrastructure

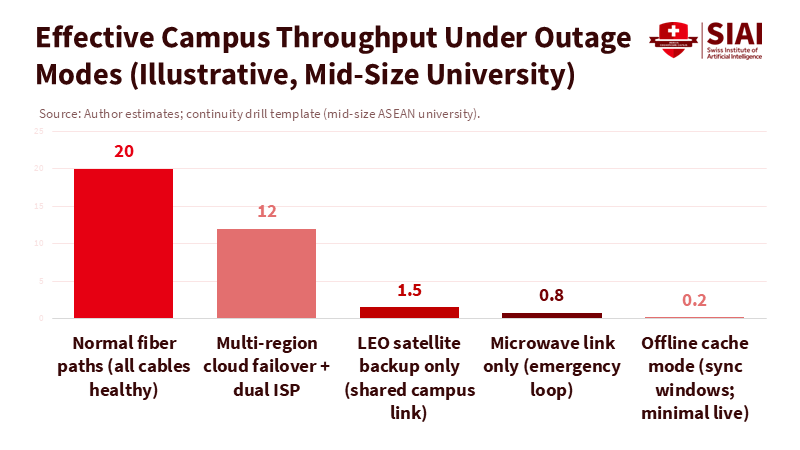

The consequences of undersea cable failures are severe. The region, with over 400 million internet users and a rapidly growing digital education presence, is at risk. Learning management systems, language apps, video platforms, and research clouds all rely on the same cables. When those cables fail, learning fails too. The physics is unforgiving. Satellites can only handle a small fraction of international capacity; they cannot replace a busy exam season or support an entire university network. During the 2023 Taiwan to Matsu cable cuts, authorities reverted to microwave links to maintain basic services. This approach ensured some data flow, but it was nowhere near what modern classrooms need. The lesson is clear: If one failure can force a return to limited emergency links, the system is not strong enough for large-scale education.

Regional cooperation is key to mitigating the risk. Much of Southeast Asia's education traffic still moves through a few hubs, especially Singapore, along with newer cloud regions in Indonesia and Malaysia. Major tech companies are adding capacity, but the pathways remain concentrated. New trans-Pacific and intra-Asia cables—Bifrost, Apricot, Echo, and others—promise new routes and lower delays. However, permitting delays have slowed several of these paths. For schools streaming lectures from Singapore or storing exam data in Jakarta, a repair delay in a neighboring country is not an abstract issue. It can result in lost class time and compliance issues related to records. Education ministries should treat cross-border cable routes like power lines: map, model, and invest in redundancy.

Lessons from Taiwan's Gray Zone for Southeast Asia

Taiwan provides a live example of how cable cuts escalate from a minor issue to a national risk. In January and February 2025, the island faced several disruptions, including one international route. Authorities detained a Chinese-crewed ship, and in July, a court sentenced its captain to three years for severing a cable near Penghu. Beijing dismissed the narrative and labeled the issue as politicized. However, the pattern is more significant than the responses. Taiwan's outlying islands had already seen back-to-back cable cuts in 2023. Investigators attributed those to a fishing boat and a cargo vessel. None of this appeared to be a conventional military move; it resembled "gray zone" pressure—subtle, deniable, but costly. Education systems would first experience that cost as jitter, delays, and downtime.

For Southeast Asia, the similarities are apparent. The most cable-heavy routes lie in contested waters and unstable geology. The Luzon Strait, between Taiwan and the Philippines, hosts more than ten major systems in an area prone to earthquakes and turbidity currents. The busy lanes of the South China Sea add risks from dragging anchors. Recent industry reports indicate dozens of publicly documented damages in 2024 and 2025, with anchor incidents and unknown causes leading the way. Global analysts caution that state-backed threats are increasing and that outages become critical when three conditions converge: limited route diversity, insufficient redundancy, and slow repair permits. These conditions exist today in parts of the region. If a gray-zone campaign targeted critical access points for education traffic, the impact would be immediate in classrooms across ASEAN.

Fix the Weakest Links in Undersea Cable Security

The solution starts before a crisis occurs. Route diversity serves as the first line of defense. Vietnam plans to increase its subsea links this decade. Singapore is adding new direct connections to North America. However, diversity on paper does not guarantee practical diversity if cables connect at the same landing spots or navigate the same permit delays. In 2024 and 2025, projects like SEA-H2X and Bifrost faced weather and permitting challenges, especially around Indonesian waters. This slowed their readiness and kept traffic focused on older routes. The region also faces a shortage of specialized repair ships. A single fault can cause delays while a vessel travels from one sea to another. Each week of delay adds costs for schools and universities that cannot shift heavy traffic to other links. Education ministries should join telecom and maritime regulators in establishing fast-track permits for emergency repairs.

Policy should emphasize speed. In late 2024, the International Telecommunication Union moved to create a global advisory body on cable resilience following a surge of incidents. Its message was straightforward: build faster, repair faster, and design for spillover risks. Southeast Asia can implement an 'ASEAN Cable Resilience Compact', a comprehensive agreement that outlines strategies and resources for maintaining undersea cable security. This compact can have three key points relevant to education. First, establish pre-approved repair routes across exclusive economic zones, allowing a ship to start work within hours, not weeks. Second, create a standing fund, supported by universal service levies and development banks, to partially finance connections to campuses and education networks. Third, implement a standard for educational continuity that mandates institutions maintain offline backups and tested emergency plans. None of this is unusual. It represents the practical redundancy needed to keep exams running smoothly when political tensions arise offshore.

Keep Classrooms Connected: A Practical Playbook

Undersea cable security must be part of institutional plans, not just national ones. Campuses should host learning platforms as close to students as possible. This means collaborating with vendors that store content in regional cloud areas and maintain copies in multiple locations. With Google and others expanding capacity in Singapore, Jakarta, and soon Malaysia, the technical framework exists to keep delays low and backups efficient. Education buyers should include these factors in contracts: regional hosting, multi-region backups, and connections at local internet exchanges. When the seabed shifts, the platform should seamlessly switch regions without any notice.

Backup paths are also necessary, but should be chosen carefully. Low-Earth-orbit satellite links serve as a safety net, not a substitute. They can keep a campus registrar functioning, support messaging, and operate a basic learning management system, but they cannot replace high-bandwidth lectures for thousands of students. The best approach combines local content caches, campus edge servers, and simplified "continuity modes" for teaching tools. Consider using recorded audio with slides instead of 4K video and asynchronous quizzes in place of live proctored exams during outages. Regular drills should be routine and straightforward. Once a semester, conduct a "dark campus" hour to test rollovers, edge caches, and communication systems. Track recovery times like you would during a fire drill. The repetitive work of practice is essential to transform undersea cable security from a plan into a standard practice.

Treat the Seabed Like a School Utility

We mentioned the 95-99% figure for a reason. Education relies on thin glass cables that cross the ocean floor. Taiwan's 2025 cable crises were not just a distant event; they previewed what a determined actor—or sheer chance—can do to a region that depends on online learning and work. Southeast Asia has options. It can diversify routes, expedite repairs, and foster resilience at the campus level. It can establish service-level agreements that require vendors to keep content nearby and to mirror it. It can conduct drills and teach faculty the difference between what is "nice to have" and what is "must have" when bandwidth is limited. Undersea cable security is not merely someone else's responsibility. It is a vital utility for schools, universities, and ministries. Securing the seabed means protecting the classroom. Ignoring it could result in more than just disrupted lectures; it might threaten the promise of accessible and collaborative learning across the region.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

ABC News. (2025, January 6). Undersea cable near Taiwan damaged in suspected sabotage.

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (2024, December 18). Subsea communication cables in Southeast Asia.

CSIS. (2022, April 5). Securing Asia's subsea network: U.S. interests and strategic options.

DCD. (2024, September 8). SEA-H2X subsea cable lands in the Philippines.

Developing Telecoms. (2024, September 6). SEA-H2X subsea cable lands in the Philippines.

East Asia Forum. (2025, October 17). Southeast Asia's undersea cables under great power pressure.

Global Taiwan Institute. (2025, March 19). Countering China's subsea cable sabotage.

Global Taiwan Institute. (2025, June 4). Taiwan's digital vulnerabilities.

Google Cloud Press Corner. (2024, June 3). Singapore data center and cloud region campus expansion.

Light Reading. (2024, December 23). 2024 in review: Submarine cables become a battleground.

Light Reading. (2025, October 6). Bifrost subsea cable now ready for commercial launch.

Recorded Future (Insikt Group). (2025, July 17). Submarine cables face increasing threats amid geopolitical tensions.

Rest of World. (2025, October). China, Taiwan, and the vulnerable web of undersea cables.

Reuters. (2025, January 15). After cable damage, Taiwan to step up surveillance of flag-of-convenience ships.

Reuters. (2025, June 13). China says Taiwan politicising cable damage issue, after ship's captain jailed.

Reuters. (2025, January 22). Taiwan activates backup communication for Matsu Islands after cable disconnects.

Stanford Cyber Policy Center. (2025, May 7). When Taiwan goes dark: Taiwan's economy depends on 14 undersea cables.

TeleGeography. (2023, May 4). Do submarine cables account for over 99% of intercontinental data traffic?

TeleGeography. (2025, February 27). How many submarine cables are there, anyway?

UNESCO GEM Report (Southeast Asia). (2025, June 10). Technology in education—A tool on whose terms?