Eurozone Policy Variability: A Key Lesson for Education Reform

Input

Modified

Eurozone heterogeneity warps school budgets and learning PISA gaps and uneven rate pass-through show one-size-fits-all reforms fail Index funding to local prices, tier pay and pathways, add cushions, and scale proven pilots

While we often engage in debates about curricula and class sizes, the topic of budgets is frequently overlooked. However, the most significant statistic for European education in the last three years did not originate from a classroom. During the peak of the energy crisis, the difference in national inflation rates within the euro area reached 18.6 percentage points. The standard variation in inflation among member states hit its highest point since the late 1990s. These disparities not only complicated monetary policy but also disrupted local education budgets, wage agreements, and households' abilities to afford costs related to schooling, like transport and rent. In other words, Eurozone policy variability—the reality that one policy does not easily apply to different places—has shaken the foundations of schools. If such significant differences can exist within a currency union, an education strategy that treats the continent as uniform will likely fail. We need reform that is tailored to each location and based on how systems actually function, with a strong emphasis on tailored funding, pay, and programs to improve equity and fairness in the education system.

Why Eurozone policy variability matters for schools

The surge in inflation across the euro area highlighted deep differences between countries that are crucial for education, not just for the economy as a whole. The European Central Bank noted a significant rise in inflation differences during 2021–2022, with only a slow return to pre-pandemic levels. These disparities affect every budget item schools rely on, including energy costs and food services. When purchasing power shifts unevenly, a national teacher pay agreement that works in one region may not be sustainable in another. A central capital program can overshoot in areas with low inflation and undershoot where costs are higher. Education policy must, therefore, learn that price dynamics differ across Europe and design funding and standards accordingly.

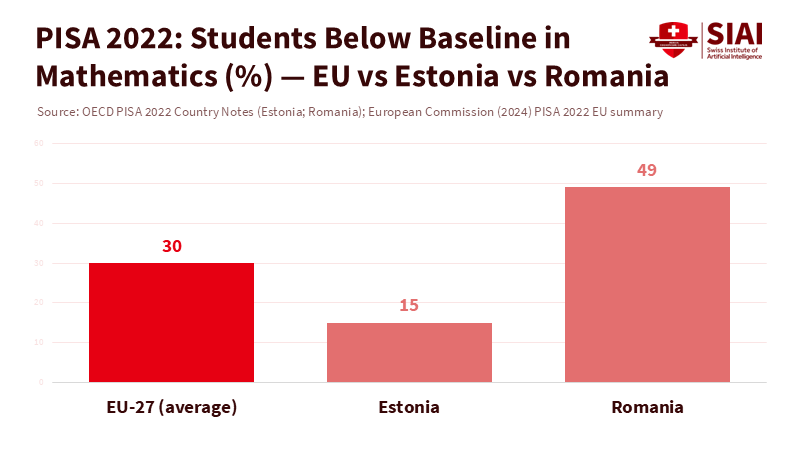

Learning outcomes tell a similar story. PISA 2022 recorded the most significant international drop in mathematics since the survey began. Nearly 30% of EU students did not reach basic proficiency in maths. However, the variation within Europe is striking: Estonia led the European table with a math score of around 510 and roughly 85% of students reaching at least basic proficiency, while Romania had only 51% at baseline, with an average math score in the 420s. This isn't a moral failure; it's a structural indicator that local systems, resources, and challenges vary. Policies that overlook these different starting points turn equity from a principle into mere rhetoric.

Monetary transmission is uneven, and education budgets feel the impact

Variability is evident not just in test results but also in Europe's financial structures. The share of adjustable-rate versus fixed-rate mortgages varies widely among member states. ECB analysis finds that about a quarter of euro-area mortgages are pure adjustable-rate mortgages, slightly more than one-third are fixed for more than ten years, and the remainder reset after a few years. Countries with more variable-rate debt transmit policy rates to households and businesses more quickly. This makes local consumption, wage negotiations, and even school donations more sensitive to changes in rates. In contrast, areas where adjustments are slower experience lags that may exceed budget cycles. For education leaders, this means that the same national formula can yield very different real-term resources in various locations at the same time.

Research on financial variability confirms this mechanism. The BIS indicates that when financial pressures mount, businesses in "weaker" regions often raise prices to maintain cash flow, while firms in "stronger" regions cut prices to increase market share, worsening regional price and wage gaps. These gaps extend beyond the private sector, impacting school procurement, transport contracts, and local labor markets. ECB and national central bank studies show that corporate and household borrowing costs respond unevenly to the same policy changes, with variable-rate markets adjusting more and faster. If the cost of money varies across locations, so will the cost of education. Education reform that assumes uniform transmission misinterprets the situation.

Designing policy for Eurozone policy variability

First, align education finance with local realities. Use rolling price indices at the regional level to adjust per-student grants, energy costs, and small capital budgets quarterly instead of annually. The ECB's data on inflation differences supports fine-grain indexing; tying budget allocations to local HICP outcomes lessens the real-term shock when energy and food prices diverge. This is not an open-ended funding strategy; it serves as protection against geographic arbitrage.

Second, tailor teacher pay structures to local cost and recruitment pressures. Education at a Glance 2024 shows ongoing differences in spending and staff costs across countries, but a national average can mask local shortages. Where shortages are acute and living costs are high, local allowances are more effective than one-off national bonuses that benefit areas without shortages. In regions with low costs and few vacancies, the same funds can be redirected to mentoring and reducing workloads. Pay policies that recognize Eurozone policy variability are not unfair; they provide a pathway to equal learning opportunities.

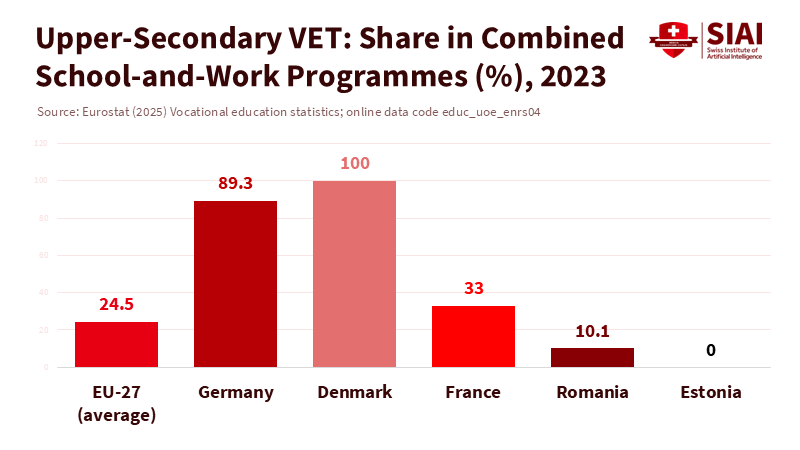

Third, connect education pathways to local economies. Eurostat reports that about half of upper-secondary students in the EU are in vocational programs, with significant differences across countries. Regions with high vocational education and training uptake can expand work-based learning more quickly; areas with weaker vocational programs need targeted investment in equipment and employer connections, rather than generic calls for increased apprenticeships. The goal is to achieve similar outcomes, not just identical inputs.

Fourth, create counter-cyclical buffers for schools where rate adjustments are most pronounced. In regions with many adjustable-rate mortgages, rate increases raise mortgage payments and reduce household disposable income, leading to increased absenteeism, unpaid meal fees, and less participation in fee-based activities. Set aside modest stabilization funds at the regional level, activated by observed increases in local lending rates or indicators of delinquency. As rates decrease, the buffer can be reduced. The aim is to mitigate the shocks that stem from differing financial structures without expecting teachers to take on social work roles.

Measure, test, and scale: a new approach to education systems

This strategy is not based on guesswork; it applies principles of organizational economics to public systems. The key insight is that policy outcomes depend on how institutions are organized—how they hire, train, contract, and respond. Recent studies suggest that effective policy design comes from modeling these organizational decisions, rather than focusing solely on the "average" household or business. For education, this means establishing policy pilots with clear adaptation rights for regions, along with transparent outcome metrics and results publication. We must be clear: uniform mandates may be easier to announce but harder to implement. Precise policies are more challenging to market but easier to maintain.

What should we test? Start with three pilots. In low-performing regions, implement targeted literacy and numeracy programs based on PISA data showing where basic proficiency is particularly low, with transparent quarterly tracking. In regions impacted by adjustable-rate mortgages, combine attendance support with transport and meal subsidies that activate when local rates surpass a certain point. In high-performing regions where improvement is slowing, focus on developing advanced skills and alleviating teacher workloads to prevent a decline concealed by national averages. None of these pilots imply permanent division; they are pathways to scaling successful strategies where they are needed.

Common objections are already known. Some may argue that place-specific policies create inequity. In reality, such inequities exist already. Evidence shows considerable differences in learning experiences and financial conditions throughout Europe. The challenge is whether we design policy with these facts in mind or disregard them. Others may express concern about administrative complexity. This is valid. However, the EU and member states already operate systems that vary based on need—such as cohesion funds, structural investments, and targeted labor-market initiatives. Education can likewise achieve this with manageable data systems and clear criteria linked to reliable sources, from Eurostat to the ECB. A final concern is political: customized policies may be perceived as favoritism. The solution is to make the criteria—and any time-limited provisions—transparent. Transparency is the simplest stabilizer.

The debate over education in Europe continues to treat the continent as a single, uniform entity. It is not. The 18.6-point inflation spread within a currency union should dispel that notion. It shows that prices, wages, and household budgets change at different rates across Europe—variations that directly impact school finances and students' lives. The latest PISA results confirm this same trend in learning: significant and persistent differences, with some systems weathering the storm while others struggle. In a landscape marked by Eurozone policy variability, a one-size-fits-all approach will not yield uniform results. To achieve true equity, we must connect financing to local costs, adjust pay where shortages exist, align paths with local economies, and support schools where financial adjustments are most severe. This is not a special plea for exemptions. It is a framework for making fairness achievable. Europe can take action now: assess the important gaps, provide regions the means to adjust, and expand what works—one place at a time, keeping one clear goal in mind.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements. (2023). Financial heterogeneity and monetary union (BIS Working Paper No. 1107). Gilchrist, S., Schoenle, R., Sim, J., & Zakrajšek, E.

Bruegel. (2016). The Eurozone needs less heterogeneity.

CEPR VoxEU. (2024). Inflation differentials in the euro area at the time of high energy prices.

CEPR VoxEU. (2025). The missing link: Why economic policy needs organisational economics.

European Central Bank. (2024). Economic Bulletin, Issue 5: The dynamics of inflation differentials in the euro area.

European Central Bank. (2025). Economic Bulletin article: The transmission of monetary policy: from mortgage rates to consumption and investment.

Eurostat. (2025). Secondary education statistics; Vocational education statistics (2023 data).

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education.

OECD. (2023–2024). Education at a Glance (editions 2023–2024).

OECD Education GPS—Estonia & Romania country notes for PISA 2022. (2023–2024).

SUERF—The European Money and Finance Forum. (2022). Highly dispersed inflation rates challenge the ECB's monetary policy strategy.

European Commission. (2024). PISA 2022: Worsening performance and deeper inequality (EU summary).