Trade Decoupling Welfare: Blocs, Prices, and the Real Risk in 2025

Input

Modified

Through 2023, trade decoupling welfare held up as flows re-routed rather than collapsed New tariffs and export controls in 2024–2025 risk delayed cost spikes and shortages by 2026 Protect education: keep open lanes, diversify sourcing, and lean on services

In September 2025, China imported no soybeans from the United States for the first time in seven years. This complete halt in shipments, where millions of tonnes once flowed, signals a significant change, even if it concerns just one commodity. It reflects a new reality: trade between rival groups is not simply being redirected; in key areas, it is being cut off. At the same time, the WTO warns that a whole U.S.–China split could reduce global GDP by up to 7% over the long term, equal to erasing the combined output of major advanced economies. Meanwhile, WTO economists still expect a 2.4% growth in world merchandise trade volume in 2025. However, they have already lowered their 2026 forecast to 0.5% as tariff impacts take effect. The lesson for education systems is urgent: trade decoupling seemed harmless through 2023. It may not stay that way as supply lines across the Pacific tighten and policy shocks add up.

Trade decoupling welfare is not a paradox; it’s a timing issue

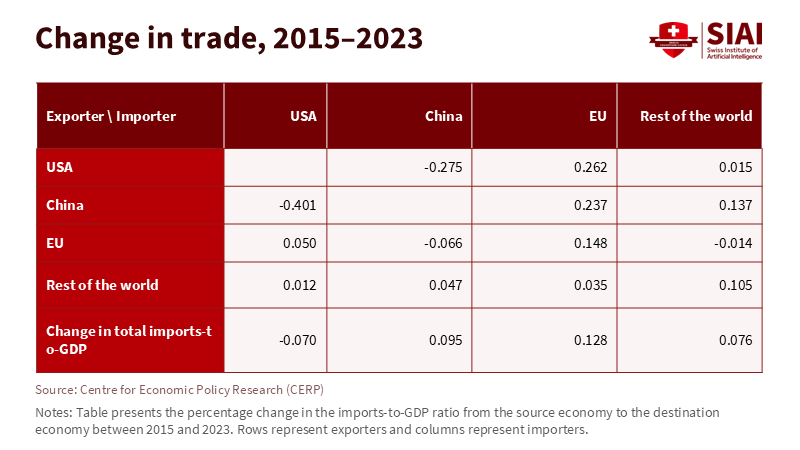

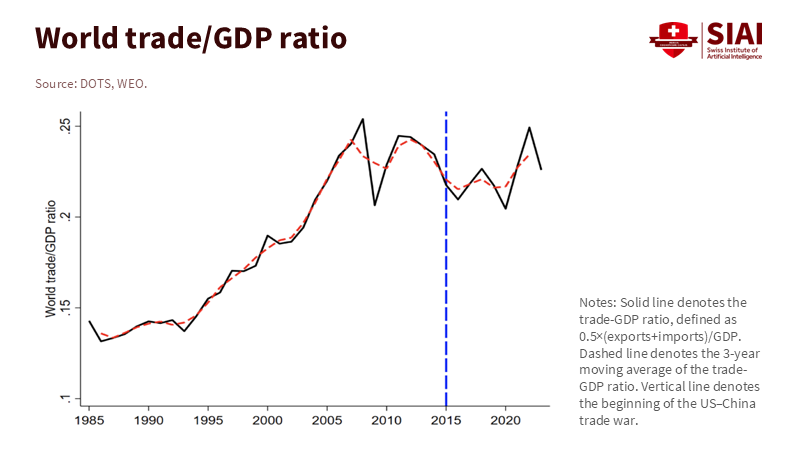

The main question in recent discussions is why the feared impact on welfare from decoupling has been smaller than expected so far. The answer lies in timing and composition. Between 2015 and 2023, the geography of trade shifted into blocs, but overall diversity and volumes remained stable. Countries traded less with adversaries and more with allies, while many remained “unaligned,” navigating between blocs. A new multi-country model using bilateral flows from 2015 to 2023 shows that the median country experienced a slight rise in real income as trade reoriented. This happened because higher costs on one route were balanced by cheaper alternatives elsewhere. In short, the past decade saw decoupling without deglobalization, which limited short-term harm to trade decoupling welfare.

This positive outcome relied on two buffers. First, substitution was possible: if one trading lane between blocs became expensive, firms switched to another lane that remained open. Second, prices were kept low by China’s industrial scale and support in the “new three” sectors—electric vehicles, batteries, and solar. Chinese EV exports surged about 70% from 2022 to 2023, flooding global markets with low-cost supplies. Additionally, inflation in wealthy countries eased through 2024 and 2025. In the U.S., the overall CPI inflation rate was around 2.9% year over year this August, with prices for durable goods remaining stable compared to pandemic-era spikes. Together, these factors explain why households, universities, and schools did not experience the broad price increases that many had predicted. The concern is that these buffers can diminish when policy changes speed up, especially when a major supplier faces increased trade barriers across several regions simultaneously.

What 2023 taught us about trade decoupling welfare

Looking back helps clarify what kept the system stable. After a weak 2023 for merchandise trade, volumes bounced back in late 2024. December data showed global trade was picking up, with the CPB World Trade Monitor reporting month-over-month growth and a stronger fourth quarter. The WTO’s outlook for 2024 and early 2025 shifted from slump to moderate expansion. This data reassured administrators buying laptops, lab sensors, or textbooks that the feared supply shortage was not happening. For educators involved in procurement, the message was clear: maintain flexible sourcing, but avoid panic about scarcity.

However, the comfort from 2023 came with a warning. The same modeling that assessed “decoupling without deglobalization” also indicated that welfare gains were fragile and depended on having open alternatives. Many countries that benefited did so by staying unaligned, buying and selling across both blocs. Meanwhile, the political landscape around bloc choices often diverged from strict economic interests, suggesting that future alignments might reduce available options. In simpler terms, trade decoupling welfare remained intact because the world still acted like a connected marketplace. If that connectivity narrows, so does the buffer. This is the risk that has increased in 2024 and 2025.

How 2025 could flip trade decoupling welfare from cushion to cost

The policy landscape has changed. In May and September 2024, the U.S. finalized significant Section 301 tariff increases on key goods from China, including a rise in EV tariffs to 100%. The European Union, after imposing temporary measures, established definitive countervailing duties on Chinese battery-electric vehicles in late 2024, framing them as a reaction to unfair subsidies. By October 2025, the WTO’s Director-General publicly urged both Washington and Beijing to ease tensions, warning that a prolonged split could cost the world 7% of GDP. These measures matter for 2025 and 2026 because tariff shocks usually take time to impact the market as inventory levels change and contracts expire. The delayed effects explain the WTO’s decision to raise the 2025 trade forecast to 2.4% but lower the 2026 forecast to 0.5%. The buffer is thinning, and the costs are being postponed.

The U.S.–China bilateral data points in the same direction. U.S. imports from China fell sharply in 2025 compared to 2024, with year-to-date shipments through July at $193.9 billion, significantly lower than the $438.7 billion recorded for all of 2024. Clear signs like zero U.S. soybean imports into China in September highlight how selective disruptions can happen, even as global trade totals remain positive. For educators and administrators, the practical effect is less about overall GDP and more about the reliability of supply and the availability of components. When trade lanes fail for specific inputs—like rare-earth magnets, certain chips, and low-end peripherals—the substitution that previously helped protect trade decoupling welfare becomes more difficult, slower, and sometimes costlier.

Policy rules to keep trade decoupling welfare positive

To maintain trade decoupling welfare as a net positive for students and schools, we should act now while trade volumes are still growing and price pressures remain low. First, we need to keep “open middle lanes.” Even as politicians raise tariffs in strategic sectors, ministries should protect education-critical goods—entry-level laptops and tablets, networking equipment for campuses, scientific sensors, and basic lab supplies—with carve-outs or fast-track licenses across blocs. This is not about appeasement; it’s a strategy for resilience. It reflects the changes through 2023 when redirection, not withdrawal, kept welfare stable.

Second, diversify suppliers inside and just outside the bloc. For Europe and the United States, this means increasing purchases from trusted partners in Asia and the Americas while still developing local capacities. This strategy is already in place for the auto and green tech sectors due to China’s overcapacity and the spillover effects of subsidies. The same approach should be applied to education supply chains. China’s production of batteries and solar products has outpaced projected global demand in some areas, and EU trade defense measures have extended beyond EVs to include mobile access equipment and other capital goods. Education buyers should seize this opportunity to secure multi-supplier agreements across Korea, Japan, ASEAN, India, Mexico, and Central/Eastern Europe, balancing cost with political risk.

Third, protect campus budgets from volatility with staggered procurement and long-term contracts that include price-adjustment clauses based on published indices. This may seem mundane, but it’s how we turn broad economic risks into local resilience. If the U.S. implements additional tariff hikes or if China imposes tighter controls on critical minerals, the likely outcome is pockets of scarcity with six to twelve-month delays. Well-planned contracts can absorb these shocks. Policymakers can support this by standardizing model clauses and creating group purchasing frameworks for public universities and school districts. As the WTO’s latest outlook suggests, the temptation is to focus on the modest growth expected in 2025; however, the absolute risk lies in the slower lane projected for 2026.

Fourth, emphasize services trade and digital openness, which are still growing rapidly and are least affected by tariffs. Training platforms, cloud-based research tools, cross-border tutoring, and credentialing services are essential for modern education. The WTO anticipates that commercial services export volumes will grow 4.6% in 2025 and 4.4% in 2026. If tangible goods trade contracts, services can shoulder more responsibility—if governments avoid splitting data and digital markets. For ministries of education, this means promoting interoperable standards, mutual credential recognition, and secure cross-border data flow rules.

Finally, prepare for transparent substitution where tariffs are long-lasting. If a 100% EV tariff signals a broader strategic split in clean-tech supply chains, anticipate spillover effects into batteries, power electronics, and charging infrastructure used on campuses. The EU’s final duties on Chinese EVs and ongoing discussions about overcapacity in solar and storage suggest there will be a medium-term re-pricing of green technology. Educational institutions moving to electric fleets or campus microgrids need to identify alternative vendors and budget for these changes now, not after lead times increase.

Anticipating critiques—and answering them with evidence

One criticism is that inflation data suggests decoupling is cost-free. With U.S. inflation near 2.9% and global growth projected to rise in October, why worry? The answer is that the impacts are delayed and selective. The WTO’s reduction of the 2026 trade forecast reflects this delay. Commodity-specific disruptions, like the halt in soybean imports, illustrate how targeted breaks can occur even while average conditions seem stable. Education systems do not purchase goods based on “averages”; they acquire components with specific chokepoints.

Another critique highlights that the costs of fragmentation are estimated and vary significantly. This is true. Estimates range from 0.2% of world GDP in mild scenarios to 7% in severe splits where adjustments are complex. However, education budgets are some of the most sensitive to price changes in the public sector, and small shifts can compound across district-wide device updates, campus energy improvements, and research equipment. The range itself signals policy action: to keep trade decoupling welfare positive, we must act before the world moves toward the bad end of the spectrum.

A third critique argues that China’s export capacity will keep prices low, regardless of geopolitics. This may be true, but only to a certain extent. The last few years benefited from significant support for EVs, batteries, and solar, along with economies of scale that brought down prices globally. However, this overcapacity has led to countervailing duties within the EU and increased tariff barriers in the U.S. These policies are not theoretical; they raise the costs of routing goods through any channel that includes targeted content. Substitution is still an option, but it is not as effective and often takes longer than it did in 2017 or even 2021.

A final critique posits that declines in bilateral trade (like U.S.–China) just mean finding new trading partners, so net welfare remains intact. Until 2023, this was mostly accurate. However, in 2025, the trends are changing: U.S. goods imports from China have sharply fallen; EU trade actions are expanding; Washington and Beijing are exchanging tariff threats; and high-profile commodities are seeing months with no imports. Redistribution works until it meets simultaneous shocks across multiple channels—and that is the current direction.

Keep the lanes open where learning depends on them

The evidence through 2023 was encouraging: decoupling changed trade patterns, but the world remained interconnected, and trade decoupling welfare stayed positive. In 2025, the signals are more ambiguous. The WTO outlook still predicts rising trade volumes in 2025 but a significant slowdown in 2026. There is a serious warning that a deep divide could cost the global economy 7% of GDP. We see sharp declines in U.S.–China goods flows and moments like the halt in soybean imports that demonstrate how quickly a trade lane can close. While education cannot control geopolitics, it can manage its exposure. The policy call is clear: keep middle lanes open for education-related goods, diversify suppliers within and across blocs, embed protective measures within contracts, leverage services trade for additional support, and prepare for transparent substitution where long-term tariffs seem likely. By taking these actions now, trade decoupling welfare can remain a positive factor for classrooms, labs, and campuses. Delaying action until 2026 could trade foresight for friction, and ultimately, students will bear the consequences of a conflict they did not choose.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025). “Consumer Price Index – August 2025.” U.S. Department of Labor.

CEPR VoxEU (2025). “Decoupling without deglobalisation: The new geography of trade blocs.” 16 October 2025.

CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis (2025). “World Trade Monitor December 2024 / February 2025 update.”

European Commission (2024). “EU Commission imposes countervailing duties on imports of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) from China.” 12 December 2024.

International Monetary Fund (2023). “The High Cost of Global Economic Fragmentation.” IMF Blog, 28 August 2023.

International Monetary Fund (2024). “Geopolitics and its Impact on Global Trade and the Dollar.” Remarks by Gita Gopinath, 7 May 2024.

Reuters (2024). “EU slaps tariffs on Chinese EVs, risking Beijing backlash.” 29 October 2024.

Reuters (2025). “China imports no U.S. soybeans in September for first time in seven years.” 20 October 2025.

Reuters (2025). “WTO chief urges US, China to de-escalate trade war, or risk long-term hit to global growth.” 17 October 2025.

U.S. Census Bureau (2025). “Trade in Goods with China.” Accessed October 2025.

U.S. Trade Representative / White House (2024). “Fact Sheet: President Biden Takes Action to Protect American Workers and Businesses from China’s Unfair Trade Practices” and Federal Register Notice on Section 301 tariff increases.

World Trade Organization (2025). “Global Trade Outlook,” 7 October 2025.

World Trade Organization (2023). World Trade Report 2023. Selected chapters and briefing materials on fragmentation costs.