Stop Pretending Subscriptions Will Save the Internet

Input

Modified

Digital ad tax won’t make users subscribe; costs are passed to advertisers and small creators Keep ads, but ring-fence a low levy to fund open education and shield SMEs with ad-credit rebates Add transparency, data portability, and a public-interest ad exchange to shift power without paywalls

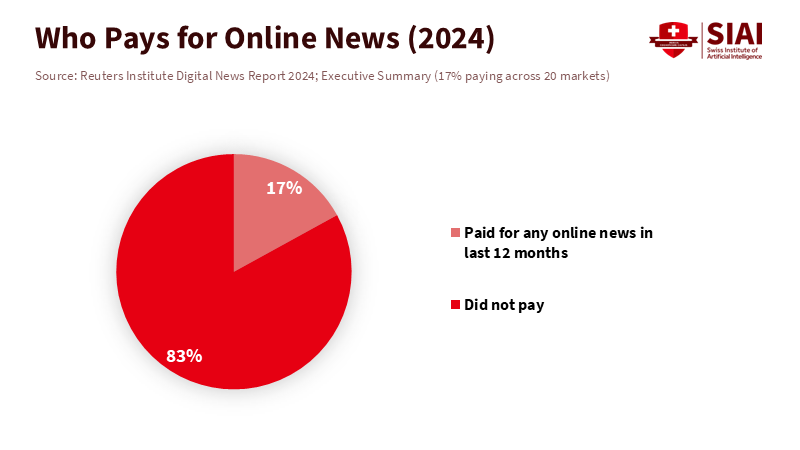

If the way we pay for information is a test, the results are in: only 17% of people in major markets paid for online news last year. That number hasn’t changed much in three years. Most readers hit a paywall and leave. They find the story somewhere else or do without it. Meanwhile, platforms keep growing. By 2025, global ad spending is expected to exceed $1 trillion, with digital ads making up three-quarters of that. The internet runs on ads, not subscriptions. A digital ad tax promises to change that by pushing platforms toward pay models and sending some revenue to the public sector. But recent evidence suggests otherwise. Courts have already rejected attempts to obscure how ad taxes are passed on, and platform financial reports show they can absorb additional costs; still, ad prices keep rising. The hard truth is simple: if we handle this poorly, a digital ad tax will increase the cost of reaching users without addressing the funding gap for quality public-interest content, including education.

The case for a digital ad tax—and where it breaks

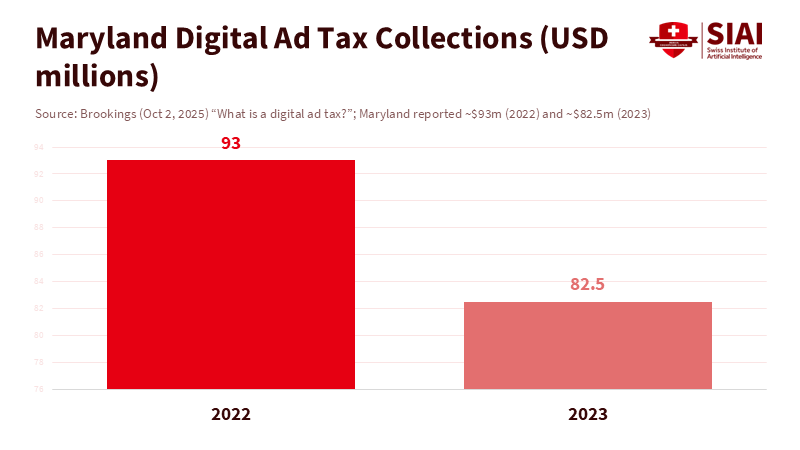

The idea sounds good on paper. A digital ad tax targets significant ad revenues, limits the power to monetize attention through tracking, and funds public resources. In practice, policy has started at the state and national levels. Maryland enacted the first U.S. tax in 2021 on large companies, with rates up to 10%. Collections have been significant—around $93 million in 2022 and $82.5 million in 2023—and designated for schools. Several European countries have similar taxes, often set in the low single digits. Advocates, including notable economists, argue that a high-rate ad tax would encourage platforms to shift away from manipulation and toward subscriptions. The narrative is appealing, but it relies on an assumption that users will pay. They usually do not.

Two developments should change expectations. First, courts invalidated Maryland’s ban on passing the tax to customers as a separate charge. This matters. It indicates that companies can raise or break down prices to account for the tax, regardless of statutory intent. Even if lawmakers maintain the broader tax, its effect will show up in the market as higher ad prices or reduced spending. Second, platform pricing shows the adjustment already taking place: Meta’s average ad price rose 10% in 2024, even before many new taxes kick in. Scale, targeting, and limited user attention give sellers an advantage. A tax changes the invoice, but it doesn’t alter the negotiating power.

A final check involves revenue mix and profit margins. Alphabet’s operating margin for 2024 was about 32%, while Meta reported 48%. Gross-revenue taxes are blunt tools; they overlook costs and can distort incentives for smaller, ad-dependent firms, such as local news outlets or niche educational platforms. Big platforms may raise prices or adjust features; mid-tier publishers and education providers have fewer options. When ad revenue shrinks or becomes more expensive, content creators feel the pressure first. That is the risk education faces if we depend too heavily on a digital ad tax as the leading solution.

Digital ad tax incidence: who really pays?

Tax theory indicates that tax burden follows demand and supply responses. In digital ads, demand is steady for crucial segments; supply is concentrated among a few platforms; and alternatives that reach similar audiences are limited. This creates an opportunity to pass on taxes to advertisers through higher prices, especially in search and social media, where measurable returns from targeting exist. The Maryland case highlighted the pass-through debate: the state tried to prevent firms from listing the tax; the Fourth Circuit ruled that this was a violation of free speech. The math is straightforward. When disclosure restrictions are lifted, sellers can explain and justify price changes. Even without a specific line item, prices can still rise. In either case, advertisers will pay more for each impression or purchase fewer impressions. Some costs are then transferred to consumers through higher product prices.

Global trends increase this effect. Digital advertising now makes up about 75% of ad spending. When a tax affects the largest channel, its impact is felt throughout the economy. The market continues to grow despite stricter privacy rules and data loss, indicating that buyers still value reach. Ad blocking remains a significant issue, affecting around 30% of users worldwide and putting pressure on publishers' profits. These dynamics suggest that a digital ad tax, especially one based on gross revenue, will likely increase effective CPMs (cost per thousand impressions) and CPCs (cost per click). This situation erodes the reach of small advertisers and squeezes the very creators and educational outlets the policy aims to support.

Another important factor for education is attention. If taxes make ad-supported distribution less profitable, platforms may reduce organic reach for public-interest content in favor of paid promotion to compensate. The losers will be classrooms, teachers, and smaller nonprofits that rely on visibility and affordable campaigns. A digital ad tax can change platform behavior. But unless the policy is narrow and carefully structured, it could steer things in the wrong direction for education providers.

What replaces ads? Not subscriptions

The hope behind aggressive digital ad tax proposals is a shift to subscriptions. But this goes against user behavior. The Reuters Institute finds that paid news remains stuck at 17% across 20 countries. Pew estimates that 83% of Americans did not pay for news in the last year. About 74% report encountering paywalls at least sometimes; many simply walk away. High turnover affects the outlets that do manage to convert readers. When markets show preferences this clearly, policy should not stake the future of information on a model most people avoid.

Subscriptions work for a small number of premium brands and dedicated super-fans. On a larger scale, they clash with substitution and oversaturation. Similar content is often available for free elsewhere. News avoidance and fatigue, where users actively avoid or feel overwhelmed by the amount of news, are increasing. Younger audiences get headlines from feeds created by the very platforms a digital ad tax targets. Even where paywalls succeed, the benefits tend to concentrate among national or global players with established brands, not local reporters or educational publishers that need steady funding the most. A broad tax that aims to force a widespread shift to subscriptions is unlikely to create a fair content market. Instead, it may widen the gap between a few winners and everyone else.

There are practical concerns as well. Subscriptions create friction. They can lead to abandonment at the moment of reader interest. This might be acceptable if the content is unique and vital. It becomes a problem if similar options are just one search away. Educational content often falls into the latter category. For teachers, students, and administrators who need reliable material quickly, the cost of time is as significant as the cost of money. We should create policies that reduce these barriers, not increase them.

A better path for education: ring-fence benefits, not business models

Suppose we accept that ads will continue to fund most of the internet for the foreseeable future. In that case, policy should focus on how the ad economy shares value and protects users. Start by repurposing the idea of a digital ad tax: implement a narrow, low-rate education tax on the ad revenues of the largest platforms, specifically designated to support open educational resources, teacher grants, and accessibility standards. Maryland already directs digital ad tax revenue to K-12 education under its Blueprint fund; however, collections have fallen short of early projections, and legal issues persist. A targeted, transparent levy at the national or EU level could avoid the complexities of state litigation while keeping the rate low enough to minimize pass-through effects.

Second, buffer the pain where it might overwhelm smaller players. Provide ad-credit rebates to small and midsize advertisers in education and nonprofit publishers that meet quality standards. Think of it as a circuit breaker for tax effects: platforms pay the levy, but small and midsize businesses that buy ads to reach students, teachers, or families receive automatic credits funded by the designated pool. This neutralizes some of the cost shift without expanding the overall tax burden beyond a narrow base.

Third, require transparency in ad targeting and allow data portability for education-related campaigns. The goal is not to eliminate relevance; it is to enable schools and publishers to transfer their audiences and first-party data across platforms easily. This diminishes platform power over time and reduces the ability to pass the tax on. Europe’s DST experience demonstrates that scope and definitions matter; a transparent system aligned with broader digital regulations is more likely to survive and effectively limit market power.

Fourth, create a public-interest ad exchange for learning. Major platforms would connect through controlled systems with specific guidelines for minors, sensitive categories, and limits on frequency. Content from museums, public broadcasters, universities, and accredited educational technology would be prioritized at fair prices. Funding from the designated tax would support operations, quality checks, and safety measures. The goal is not to choose winners but to increase the discoverability of trustworthy educational content without forcing subscriptions on a market that rejects them.

Finally, test a data dividend for learning. Instead of directing all tax proceeds to general revenue, set aside a portion for student and teacher accounts in the form of micro-grants redeemable for vetted educational materials. This concretizes the principle that “the data generator gets paid” while avoiding the challenges of paying individuals cash for clicks. It also ties revenue directly to outcomes that matter for schools.

Anticipating the critiques

One critique claims a digital ad tax will consistently stifle innovation and overreach since platforms already pay corporate taxes and employ thousands of people. The solution lies in targeting. A narrow tax focused on specific educational outcomes, paired with ad-credit rebates for small and midsize businesses, respects existing tax frameworks while acknowledging the unique, concentrated profits in digital advertising. The scale is the key point: with digital capturing about 75% of ad spending, even a small tax can fund lasting public goods without pushing every content creator behind a paywall.

Another critique counters that any tax is too insignificant to change behavior at the top. Evidence supports both views. Alphabet and Meta report high profit margins, suggesting they can absorb extra costs. However, rising ad prices indicate that we might pass on costs if we push too hard. The goal is to find a balance that is low enough to avoid broad price increases but high enough to avoid being merely symbolic. That’s why a low-rate, targeted approach combined with measures to enhance competition is better than a high-rate, blunt tax aimed at forcing subscriptions. This strategy seeks to promote shared value rather than shock treatment.

A third critique argues that we should implement bold solutions to address the issues in the attention economy. Real problems exist. Policymakers are testing school phone bans, safety standards, and labeling. However, revenue tools are not the best means for content governance. Use product rules to reduce harm, apply a focused tax to fund alternatives, and promote transparency to rebalance negotiation power. Mixing these strategies invites legal challenges and undermines each element.

Start where users are, not where we wish they were. The internet runs on ads, and an expansive digital ad tax will not create a willingness to pay where none exists. The average reader chooses not to subscribe, while the typical advertiser still needs to reach a broader audience. The platforms sit between them, leveraging scale and targeting to demand higher prices. Courts have clarified that pass-through cannot be concealed, and evidence of pricing indicates it is already occurring. The challenge for education policy is not to force a return to a century-old subscription model. It is to shape an ad-funded internet that supports learning: a narrow tax designated for education, ad-credit rebates to protect small players, portability and transparency to restore competition, and a modest data dividend that returns value to classrooms. This approach acknowledges the market’s judgment on subscriptions while redirecting part of the ad engine’s power toward the public good. We should pursue it—and measure success by the quality, reach, and affordability of learning that follows.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Johnson, S. (2024). The Urgent Need to Tax Digital Advertising. MIT Shaping the Future of Work (Policy Brief). April 2024.

Alphabet Inc. (2025). Q4 and Fiscal Year 2024 Results: Operating margin expanded to 32%. U.S. SEC Exhibit 99.1, Feb. 4, 2025.

eMarketer / Insider Intelligence. (2025). Worldwide Ad Spending Forecast 2025: Total spending to exceed $1T; 75% digital. Jan. 28, 2025.

Maryland Court of Appeals (Fourth Circuit). (2025). Chamber of Commerce v. Lierman, No. 24-1727 (Aug. 15, 2025) (opinion PDF).

Meta Platforms, Inc. (2025). Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2024 Results: Operating margin 48%; price per ad +10% YoY. Investor relations press release; SEC Exhibit 99.1.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. (2024). Digital News Report 2024: Executive Summary (17% paying for online news across 20 markets). June 17, 2024.

Tax Foundation. (2025). Digital Services Taxes in Europe, 2025 (jurisdictions with enacted DSTs). May 6, 2025.

U.S. Appeals Court coverage. (2025). Part of Maryland digital ad tax law declared unconstitutional (Reuters). Aug. 15, 2025.

U.S. Appeals Court coverage. (2025). Maryland tax on digital ads violated Big Tech’s free speech, judges say (AP). Sept. 2025.

University of Oxford / Reuters Institute. (2024). How much do people pay for online news? (17% paying; stagnation). June 17, 2024.

U.S. Pew Research Center. (2025). Few Americans pay for news when they encounter paywalls (83% did not pay; 74% meet paywalls at least sometimes). June 24, 2025.

Brookings Institution (Nguyen, C., & Seamans, R.). (2025). What is a digital ad tax? (history; Maryland revenue figures; DST overview). Oct. 2, 2025.

Backlinko (GWI data). (2024). Ad Blocker Usage Statistics 2024 (≈31.5% of internet users use ad blockers at least sometimes). Sept. 2, 2024.