Institutional Differences in Education Policy: East-West Governance After the Shock

Input

Modified

East and West govern schools differently These institutional differences shaped learning losses and recovery Western systems need directed autonomy; Asian systems need lighter admin with teacher discretion

One crucial figure should guide our school designs for the next decade: from 2018 to 2022, average mathematics scores across the OECD dropped by about 15 points, while reading scores fell by about 10. This represents the most significant decline in the program's history. The decline spanned income levels and political backgrounds. We can attribute part of this issue to the pandemic, but the extent and spread of the drop reveal more profound insights about how educational systems are designed. Learning depended on how quickly decisions, staffing, and resources could respond when classrooms closed. This leads us to the differences in education policy between institutions. East Asian systems usually centralize key decision-making, while many Western systems delegate authority to districts and schools. These are not mere cultural quirks. They represent operating systems that either enhance or weaken responses to crises. If we want a solid recovery, we should view governance as a key factor that defines what classroom reforms can accomplish.

How institutional differences in education policy affect recovery

The shock made a harsh reality clear: learning losses were not the same everywhere, and resilience depended on governance. Where a national authority maintained control over curriculum, staffing, purchasing, and data, decisions were made swiftly and on a large scale. When authority was fragmented, millions of small choices had to be coordinated, and many failed to do so. PISA 2022 shows that systems that kept more students from prolonged closures generally performed better and reported a stronger sense of belonging in school. However, the same OECD analysis warns that there is no straightforward connection between the length of closures and performance trends across countries. The takeaway is not that centralization is the only solution. Still, rather than the design of institutions influencing the speed and coherence of the response, speed is crucial because every lost week adds to the overall loss.

Recovery will falter if we overlook basic reading skills. In low- and middle-income countries, learning poverty—the percentage of 10-year-olds who cannot read and understand a simple text—was estimated at 70% in 2022. This problem is not far removed from the worries of wealthier systems. Many Western countries experienced sharp declines in foundational skills, while numerous Asian systems put immense pressure on teachers and students. The issue is not about who performed better. It is about how governance—how authority and accountability are organized—shaped the crisis and the initial recovery. We need to tailor interventions to the systems we have, not the ones we wish we had. This involves providing guidance where freedom has led to chaos and allowing some flexibility where control has become overwhelming.

What recent data reveal about the centralized East and the decentralized West

The East-West contrast is seen in how decisions and resources are distributed. Singapore centralizes strategic control in its Ministry of Education while allowing schools some flexibility to adapt. It ranked highest in PISA 2022 in mathematics, reading, and science among 81 systems, even after significant disruptions. This does not establish that centralization directly causes high performance, but it does illustrate how strong coordination and clear priorities can provide stability during stressful times. Japan and Korea also managed to avoid the steepest declines. In contrast, several Western systems with dispersed authority struggled to align curricula, platforms, and teacher support quickly. The main point is clear: during a crisis, coherence can be a valuable resource, and some systems are designed to access more of it.

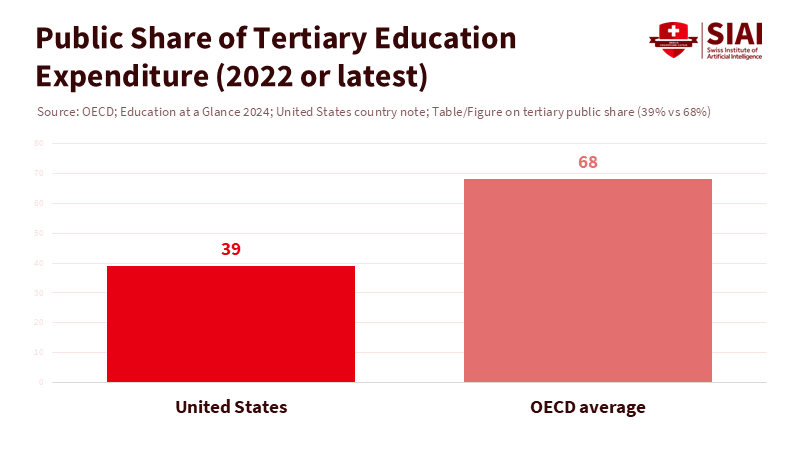

The financial aspect reveals a similar divide. China reported total education spending of RMB 6.4595 trillion in 2023, marking a 5.3% increase from the previous year, with compulsory schooling being the most significant expense. This signifies a central government using its budget to expand coverage and equity on a large scale. On the other hand, at the tertiary level in the United States, only about 39% of spending comes from public sources, which is significantly lower than the OECD average of roughly 68%. This reflects a greater role for private funding and a more fragmented policy landscape. High spending does not ensure resilience if funding and decision-making are split across various levels. In a crisis, the key issues are who can set a baseline, who can fund it, and who can implement it quickly.

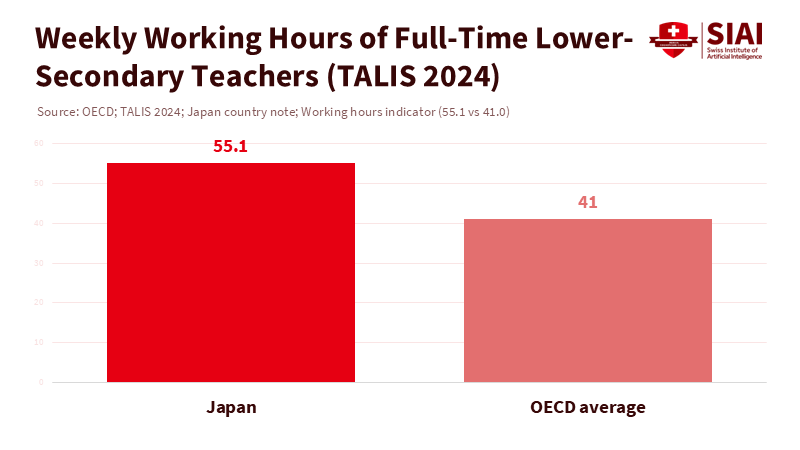

People, not just policies, bear the burden. Japan's centralized model ensures uniform standards, but it also results in very long teacher workloads. TALIS 2024 reports that full-time lower-secondary teachers in Japan work about 55.1 hours per week, compared to an average of 41 hours across participating systems. This level of stress threatens teacher well-being and limits time for planning and collaboration—critical activities that support quality when under pressure. Governance can mobilize resources; it must also safeguard the individuals who translate policy into effective learning.

Directed autonomy for Western systems

Western systems often value agency at the school level. This principle does not need to change. However, recent years have shown that autonomy without guidance can scatter efforts when quick and consistent action is necessary. A better solution is directed autonomy: establishing a central baseline for essential needs, providing shared resources, and promoting networked delivery—all while allowing local adaptation.

We should start with a national baseline for foundational skills and monitoring. After the PISA decline, systems that maintained consistent teaching time and monitored learning during closures fared better in terms of confidence and outcomes. Central authorities should require simple, transparent assessments for early-grade reading and math and offer a common data platform. Schools can choose their teaching methods, but the center must ensure comparability, portability, and a rapid response when indicators decline. The resilience chapter of PISA 2022 emphasizes that systems that keep more students engaged and prepare them for remote, more independent learning managed the crisis more effectively. Western ministries can quickly expand these foundational components without micromanaging classrooms.

Next, we should centralize the procurement of high-quality materials and tutoring while localizing the delivery. When every district negotiates platforms and programs independently, costs increase, and quality suffers. A centralized catalog of vetted curricula and proven tutoring services available for bulk purchase can speed up time-to-classroom. Schools can then select from this catalog and schedule based on their students' needs. The goal is to minimize obstacles—such as contracts, compliance, and logistics—so principals and teachers can concentrate on teaching. Lastly, we need to foster connected improvement. Decentralization should not lead to isolation. We should fund formal "school-to-school" partnerships with clear objectives and transparent progress reporting, and allow time for shared coaching among groups. The state sets the framework; schools drive the efforts.

Guardrails for state-led systems in Asia

State-led systems face a different risk: excessive control. Central ministries can accomplish great things, but they can also overwhelm teachers with tasks. Japan's working hours data serves as a warning. The priority now is to maintain the benefits of coordination while allowing for greater professional discretion. This begins with addressing workloads. Ministries should limit non-teaching responsibilities and make paperwork optional by default. We should fund operations personnel at the school level and simplify oversight of extracurricular activities to free up teaching time. As hours decrease, opportunities for planning and collaboration increase, leading to better quality.

Next, we should refine the curriculum. Clearly define critical outcomes, then permit various high-quality pathways to achieve them. Singapore exemplifies how coherence and innovation can coexist by setting strict goals while encouraging flexibility. The PISA results not only show high scores but also reveal resilience during difficult times. Systems that kept more students in school and maintained teacher access during closures performed better. East Asian ministries can retain that resilience while reducing teacher burdens: fewer mandatory tasks, more professional choices in the classroom, and targeted assistance based on formative data. When inequities remain, the centralized authority should direct resources effectively. Shanghai's "empowered-management" model—contracting high-performing schools to improve struggling ones over set periods—demonstrates how central authorities can promote improvement by creating structured networks instead of relying solely on top-down mandates. Evidence suggests that it has raised performance in lower-performing schools, and this approach can be adapted elsewhere.

The notable drop of about 15 points in mathematics and about 10 points in reading across the OECD served as a stress test. It uncovered structural weaknesses while highlighting strengths. Differences in education policy are not just labels; they define how quickly actions can be taken when faced with challenges. Western systems should adopt directed autonomy, establishing a clear central baseline for essential needs, shared resources and data, and robust school networks to facilitate the exchange of knowledge. State-led systems should implement safeguards: lighter workload, streamlined mandates, and more space for teachers to focus on teaching. Both types of systems should base recovery on transparent measurements of foundational learning, with rapid funding for the most urgent needs. If we construct governance structures that ensure timely and well-placed decisions, the next crisis will not undo a decade of progress. Instead, it will find systems ready to adapt without collapsing, along with students who continue to learn when circumstances become difficult.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Ministry of Education, People's Republic of China. (2024, July 23). MOE releases 2023 Statistical Bulletin on Educational Expenditure (Press release).

OECD. (2023, December 5). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education.

OECD. (2023, December 5). PISA 2022 Results (Volume II): Supporting Students to Succeed. Chapter on resilience.

OECD. (2024, September 10). Education at a Glance 2024: OECD Indicators—United States country note.

OECD. (2025, October 7). Results from TALIS 2024—Country notes: Japan.

OECD. (2023, August). Enhancing school improvement reform in New South Wales, Australia. (Note on Shanghai's empowered-management programme).

Singapore Ministry of Education. (2023, December 5). Singapore's strong showing in PISA 2022 affirms resilience of education system through COVID-19 pandemic (Press release).

World Bank; UNESCO; UNICEF; FCDO; USAID; & Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (2022, June 23). 70% of 10-year-olds now in learning poverty, unable to read and understand a simple text (Press release).