From Volume to Voice: fixing the monetization gap in China's soft power

Input

Modified

China’s soft power problem is monetization, not creativity Shift incentives to export outcomes, licensing, and private experimentation Let partners localize, focus on proven genres, and flip the IP receipts–payments gap

China has climbed to No. 2 in a leading global soft-power ranking with a score of 72.8 out of 100, surpassing the UK for the first time. However, public opinion in many countries remains largely negative. In mid-2025, a median of 54% across 25 nations viewed China unfavorably, while only 36% viewed it favorably. Both can be true at the same time. The index measures perceived potential in areas such as media, science, and business, while opinion polls reflect everyday sentiment. This gap highlights a key issue: China already produces outstanding culture, but is not earning enough from it and struggles to turn domestic praise into lasting affection abroad. The solution is not simply making more or being louder. It requires refining quality, taking bolder editorial risks, and speeding up feedback targeting export markets. There should also be a strong effort to turn stories into income through intellectual property. In summary, China's soft power will improve when it focuses on selling rather than shouting.

Reframing the problem: China's soft power is a monetization issue, not a capacity issue

We should stop questioning whether China creates 'good' culture. The answer is clear on the festival circuit. In 2024, Guan Hu's Black Dog won Un Certain Regard at Cannes. In 2025, Huo Meng received the Silver Bear for Best Director in Berlin, and Xin Zhilei won Best Actress in Venice. These honors are significant. They demonstrate skill, variety, and world-class direction and acting. The bottleneck occurs after these awards, at the stages of distribution, packaging, and international editing. China's domestic box office is massive, but the versions of films, series, and formats that are 'export-ready' often struggle to reach paying audiences who might buy soundtracks, merchandise, or theme park days. By 'export-ready', we mean products that are culturally adaptable and appealing to international audiences. China's soft power weakens not due to a lack of art, but because of inconsistent methods to convert screen appeal into profit in target markets.

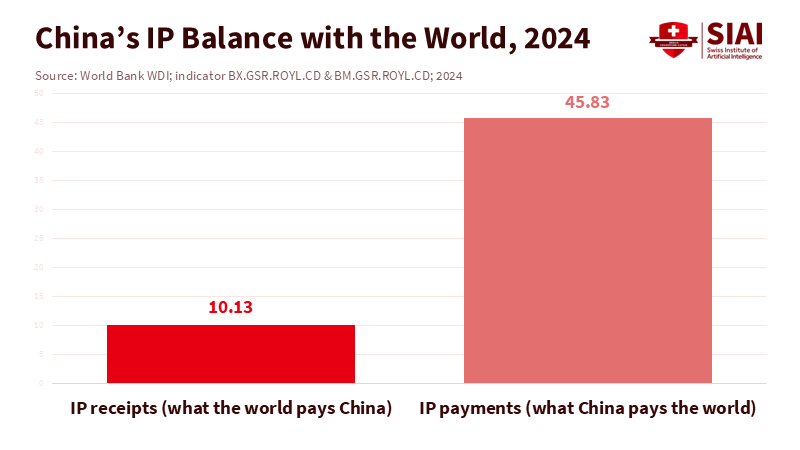

This gap is starkly evident in balance-of-payments data. In 2024, China received approximately $10.1 billion from intellectual property use, which is what others pay China to license its IP. In contrast, China spent around $45.8 billion on others. The net outflow indicates that Chinese stories, characters, and formats generate less value abroad compared to foreign IP in China. In comparison, South Korea's policy system is consistently turning cultural IP into strong exports. In 2024, its IP exports reached around $9.85 billion, even though goods exports far exceeded this total. Japan's anime industry earned an estimated $19.8 billion globally in 2023, with merchandise significantly contributing to this revenue. The limitation is not China's capacity, but its conversion. China's soft power will advance most when the difference between IP receipts and payments shifts positively.

A final reframing is essential. Many discussions treat soft power as a moral issue—if Beijing communicated less and listened more, audiences would appreciate it. Public opinion is improving slightly, but reputation is sticky, and political cycles can be disruptive. Therefore, the strategy should focus on what the cultural economy can control: the story-to-sale process. This is where policy can encourage private experimentation, facilitate larger licensing deals, and generate more revenue from Chinese IP abroad. China's soft power grows when successful productions, such as 'The Wandering Earth' or 'Ne Zha', travel well, in-market partners can tailor content, and creators share profits that reward taking risks.

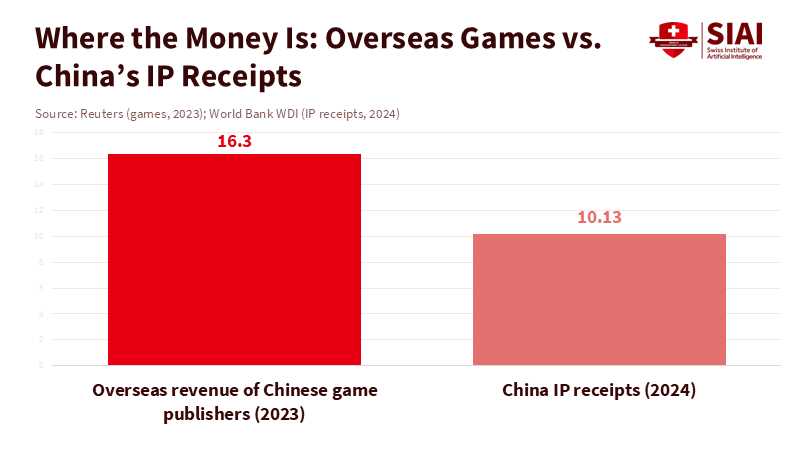

What the data actually says about China's soft power in markets

Start with the primary trend: the 2025 Global Soft Power Index ranks China second overall, with increases in six out of eight pillars, but it only sits at 27th in terms of reputation. Public-opinion data from Pew shows a similar split. There has been some warming since 2024, but the overall view remains negative. Moreover, the entertainment market is still cyclical. The global box office in 2024 dropped to $30 billion, while international revenues (excluding China) reached $21.2 billion, creating a challenging environment for films that require time and significant investment to build an audience. Currently, the quickest cash is found in mobile games and animation. Chinese game publishers made $16.3 billion overseas in 2023, demonstrating that when the product-market fit is strong and operations are effective, Chinese IP can thrive abroad. This should be the model: focus on specific genres, such as action-adventure and fantasy, conduct ongoing testing, and incorporate monetization from the start.

Looking at competitors clarifies the strategy. Korea has spent the last two decades developing an export-ready system where studios and platforms compete for international market presence. The government facilitates and co-finances but mainly steps back. When successful projects emerge, the private sector handles global distribution, format sales, merchandise, and touring. This model is evident in trade statistics and in how organizations like KOCCA manage pipelines. Japan's anime success is even more apparent: the profits come from global licensing and merchandise rather than domestic TV. The lesson for China's soft power is clear. If revenues come primarily from outside the home market, creative choices must be evaluated in international markets as well.

Evidence from the goods side warns against complacency. China currently leads the EU in imports of "cultural goods" by value—31.6% in 2023. Still, this category mainly includes consoles and jewelry, rather than drama formats and characters. It's easy to mistake manufacturing strength for cultural preference. Genuine soft power turns appreciation for stories into a willingness to license IP. This process requires building trust with global buyers, providing consistent products, and allowing local partners the freedom to adjust tone, pacing, and endings to suit local audiences. China's soft power will expand most rapidly if the system stops viewing export edits as a loss of cultural essence and starts seeing them as a way to broaden cultural reach.

What to change now: from scale to sophistication in China's soft power-Urgent strategic changes needed

First, revise the incentives. Shift selective subsidies away from production counts and focus them on export outcomes. Connect government support to measurable foreign revenues—licensing, streaming revenue abroad, merchandise sales—and to evidence of market testing. Reward films and shows that create multiple versions for different regions and run structured test screenings in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America before global release. This approach is how K-content scaled: learning from many failures, maintaining disciplined feedback, and allowing funds for experimentation. Use state resources to attract private investors who are willing to take on market risk while keeping decision-making in private hands. China's soft power will mature as success metrics shift from "minutes produced" to "profits earned abroad." (For policymakers concerned about reputation, it's worth noting that global favorability can rise even amid political tension; data since 2024 shows slight increases.)

Second, create a licensing framework that compensates creators for taking export risks. Current balance-of-payments data shows a consistent outflow of IP. Reverse that trend with a three-part solution: an international rights contract that ensures fair revenue sharing, a government-backed facility that provides cash advances against foreign licensing deals, and a "writers-room exchange" that connects Chinese showrunners with global editors and story consultants for entire seasons rather than just pilots. The aim is to reduce costs and cultural misunderstandings that can derail promising projects abroad. When characters are designed with licensing in mind—by using clear archetypes, adaptable settings, and opportunities for games and webtoons—China's soft power can earn while also persuading.

Third, concentrate on genres where China is already succeeding with international audiences: mobile action RPGs, sandbox shooters, xianxia romance, and crime dramas. Games set a clear example. Publishers continually test, learn from user data, and build loyalty that can later fund animation, live-action series, and concerts. Apply this logic to film and drama by creating season arcs that support DLC-style side stories, timing character releases to holidays in target markets, and forming partnerships with Southeast Asian streamers who can quickly introduce local stars. Suppose the quality remains high and the production pace stays quick. In that case, awards will follow, serving this time as a starting point for sales rather than a concluding chapter. China's soft power grows when creative and commercial risks are managed together.

Finally, introduce a vital reform: export-market editing rights. Many coproductions stall because partners cannot modify endings, comedic timing, or cultural references to fit local norms. Establish a transparent framework for "international versions" that allows necessary adjustments while maintaining key aspects of the work. This is how Japanese anime and Korean dramas expanded—they didn't try to please everyone with a single version. Still, they sent versions tailored for each audience while keeping the core of the original intact. Black Dog won at Cannes because its structure and pacing were tight enough to resonate with international audiences. Providing global partners the room to make necessary changes will lead to more licensing opportunities.

Anticipating the pushback—and answering it with evidence

One criticism argues that soft power cannot thrive without political trust, suggesting that the cultural strategy won't work. Reputation matters, but it changes slowly and inconsistently. The 2025 Pew data indicate a slight shift toward global warming in China, even though many still hold negative views. Simultaneously, the Brand Finance index shows significant improvements in influence and recognition, moving China up to second place overall. Culture may not erase political issues, but it can navigate around them by identifying niche audiences and monetizing them. This is how anime and K-pop grew despite their constraints. The implication for China's soft power is to view political challenges as a cost of doing business and focus on long-term strategies rather than short-lived popularity.

A second critique claims that "quality is the issue." Festival juries would disagree, as would international gamers and animation buyers. The real challenge lies in consistency: too many projects are treated as standalone prestige bets rather than as opportunities to develop a stable of IP. This is reflected in the IP accounts: while $10 billion in receipts is significant, it pales in comparison to payments. It is minor relative to China's creative output and manufacturing reach. The solution is not one blockbuster hit but a pipeline that nurtures more minor successes in the same genres—much like what Japan's anime industry has achieved with impressive discipline. The goal is not just acclaim but revenue that builds over time. China's soft power becomes sustainable when international consumers choose Chinese characters not out of love for China, but because they enjoy the story.

A third critique suggests that merely reducing state involvement will resolve the issues. However, this is not the answer. Korea's government did not simply vanish; it established frameworks for coordination, export financing, and training while allowing private companies to make decisions. China requires a similar division of responsibilities: the government addresses coordination issues and mitigates risks for private investment. At the same time, creators test, fail, and learn. Suppose policymakers want a clear indicator of whether China's soft power is on the right path. In that case, they should monitor one number: the ratio of overseas IP receipts to payments. Once that changes, progress will follow.

The call to action

According to the index, the world sees China rising. However, polls show that many are not yet convinced. This tension is not a paradox; it's a roadmap. Focus on the areas where the data is most impactful. In 2024, China spent around $46 billion on using others' IP and earned about $10 billion from its own while exporting world-class films, large-scale games, and fast-developing dramas. Korea and Japan demonstrate how to bridge that gap: establish export-friendly incentives, create robust licensing operations, and allow editors and distributors flexibility. The successes at film festivals—Cannes, Berlin, Venice—show that artistic quality exists. The next step is to transform these accolades into the beginning of a commercial story rather than the conclusion. Suppose the system directs more resources and authority to private creators, allows for experimentation, and defines rights for international versions. In that case, China's soft power will shift from chasing opinions to generating real value.

This is not merely about being louder. It's about earning revenue for what already resonates and quickly adjusting to what doesn't. If this is accomplished, the figures will change. IP revenues will increase. Fans will purchase sequels and merchandise. Global recognition will deepen into genuine affection. The next time a Chinese film takes the stage in Europe to accept an award, the more significant prize will already be in motion: characters and stories that the world chooses to invest in. That is how potential becomes power—and how China's soft power shifts from being a topic of debate to a tangible asset.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Alliance of Democracies Foundation. (2025, May 12). Global perceptions of US fall below China, survey says (Reuters report).

Brand Finance. (2025, Feb 20). Brand Finance Global Soft Power Index 2025: China overtakes UK for the first time, US remains top-ranked nation brand.

Brand Finance / Brandirectory. (2025, Feb 20). Global Soft Power Index 2025: The shifting balance of global Soft Power.

Deadline. (2025, Jan 15). Global box office 2024 report: Hollywood studio rankings.

Eurostat. (2025). Culture statistics—International trade in cultural goods (2023 data update).

Gower Street Analytics. (2025, Jan 8). Sparkling December finishes 2024 on high with $3bn; global box office 2024 total $30bn.

Parrot Analytics. (2024, Dec 19). Japanese anime captured $19.8 billion in 2023 global revenue.

Pew Research Center. (2025, Jul 15). International views of China turn slightly more positive.

Reuters. (2024, May 24). 'Black Dog' wins Un Certain Regard competition at Cannes.

Reuters. (2025, Feb 22). Norwegian film wins Berlin's Golden Bear; China's Huo Meng takes Best Director.

Reuters. (2025, Sep 6). Toni Servillo, Xin Zhilei win top actors' awards at Venice.

Reuters. (2023, Dec 14). China's video-games market recovers; overseas revenues $16.3 billion.

Reuters. (2025, Aug 21). South Korea turns to culture in search of next fillip for growth.

World Bank (WDI). (2025). Charges for the use of intellectual property, receipts (BoP, current US$): China (2024 value ≈ $10.1 billion).

World Bank (WDI). (2025). Charges for the use of intellectual property, payments (BoP, current US$): China (2024 value ≈ $45.8 billion).