Classrooms in the Crossfire: Education Policy in an Age of Oil Diplomacy

Input

Modified

Oil diplomacy now shapes school budgets, student mobility, and campus operations Japan’s hedging between U.S.–Israel ties and Arab energy suppliers previews the new normal Education leaders should hardwire energy resilience and principled, diversified academic partnerships

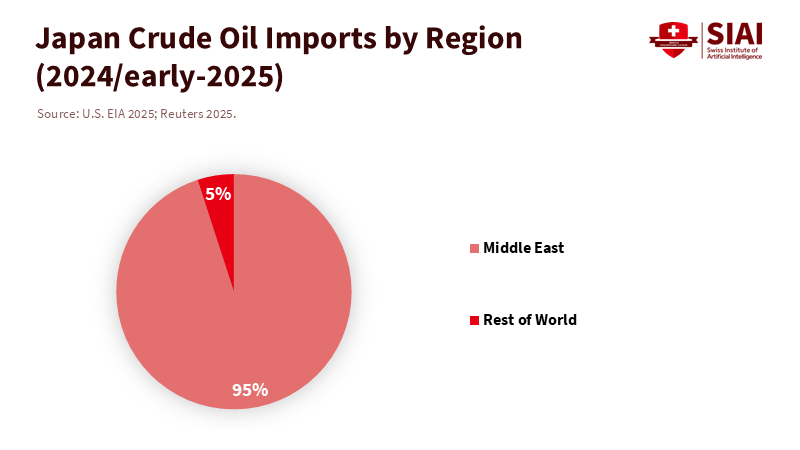

Ninety-five percent of Japan's crude oil comes from the Middle East. This dependency turns a distant airstrike into a domestic education issue overnight. When Israel struck Iranian targets on June 13, Brent crude prices rose about five dollars to the mid-$70s in just hours. Markets began to factor in the risk that one-fifth of the world's oil supply could be affected at the Strait of Hormuz. School buses do not run on geopolitics, but they rely on diesel fuel. University labs utilize electricity that fluctuates in price in tandem with the oil and gas markets. Construction budgets for new campuses feel these shocks, but not immediately. What seems like a minor diplomatic dilemma—how to balance relationships with Washington and Jerusalem without upsetting Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, or Tehran—lands in school district budgets within weeks. Education systems that ignore these issues are setting themselves up to face the consequences anyway.

Japan's recent public statements highlight this predicament. Tokyo initially labeled Israel's June strikes on Iran as "totally intolerable." Days later, it called for de-escalation and notably refrained from criticizing Washington's own attacks, indicating a careful approach to alliance management as energy security concerns grew. By late June, Japan distanced itself from a Group of Seven stance that many saw as too aggressive; this was a subtle signal of caution. We can dismiss this diplomatic dance as unimportant, or we can recognize it for what it is: a nation whose schools, universities, and research budgets are feeling the effects of commodity risks more than most, trying to keep both cheap fuel and strong international connections from disrupting its classrooms. This is not just Japan's issue. It has become the new norm for any education system that depends on global energy markets and recruits students from various political backgrounds.

The education sector's first mistake would be to treat these fluctuations as background noise. They are a fundamental aspect of an oil market where supply investment remains stagnant, decline rates are increasing, and geopolitical risks can change rapidly. In June, the IEA noted that Brent prices rose five dollars immediately after the June 13 strikes, despite comfortable stock levels and healthy non-OPEC+ supply growth. Prices later dropped, but this episode demonstrated how quickly risk premiums can re-emerge. The World Bank has warned that even a moderate disruption from conflict could push Brent into the $90s and a severe one beyond $100, adding nearly a percentage point to global inflation. Education budgets, constrained by regulations and cycles, do not adjust that quickly. Planning under the assumption that they will adapt is unrealistic.

Why Alignment Choices Show Up on Campus Ledgers

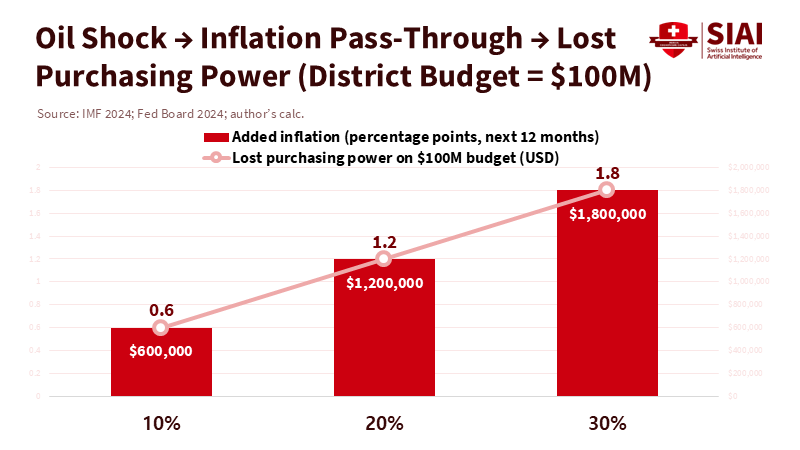

Oil price shocks impact education finance through two main channels: energy expenses and the inflation effect on other costs. We have reliable estimates for the latter. Research from the IMF indicates that in countries with high oil exposure, a 10 percent increase in oil prices adds 0.7 percentage points to headline inflation over twelve months. Analysis by the U.S. Federal Reserve estimates that the immediate impact on U.S. headline inflation for a similar oil price increase is about 0.15 percentage points, highlighting variations between countries but acknowledging a significant pass-through effect. For schools, this means that if a district plans a $100 million operating budget with a 3 percent growth expectation, an added 0.5 to 0.7 percentage points translates to a loss of $500,000 to $700,000 in purchasing power without any new revenue. This could mean the cost of one special-education van or the choice between replacing a failing cooling system now or delaying it for another year. The pass-through range combines the IMF's high-exposure estimate with the Fed's model to suggest plausible outcomes for systems that depend on imports.

Then there is the direct energy bill. U.S. K-12 districts spend nearly $8 billion a year on energy, making it the second-largest expense after salaries, while K-12 buildings account for around 9 percent of commercial building energy consumption. In higher education, the 2024 Higher Education Price Index rose 3.4 percent, with rising utility costs among the factors. Many districts report double-digit increases in electricity bills; one district in Connecticut, for example, budgeted for a 16 percent increase in electricity costs. These are not isolated U.S. stories; they provide insight into how energy volatility affects public-sector budgets.

Diplomacy in the Lecture Hall: Student Mobility, Scholarships, and Research Ties

The second way oil prices affect education is through people rather than just costs. Japan hosted a record 336,708 international students as of May 1, 2024, to reach 400,000 by 2033. These students—and the faculty who teach and work with them—come through networks that connect the Gulf, North Africa, the Levant, and Israel as much as East and South Asia. Saudi Arabia plans to send about 70,000 scholarship students abroad by 2030 as part of its Vision 2030 initiative. Education leaders who believe that oil politics are far removed from admissions or partnerships have not examined the situation closely. Prestigious scholarships, endowments, bilateral research funding, and logistical support for fieldwork flow through capitals that are actively balancing relations between Israel, the U.S., and the Arab world.

Schools cannot dictate foreign policy, but they can interpret the signals. Japan's summer statements—criticizing Israel's early strikes, advocating for de-escalation, avoiding criticism of U.S. actions, and creating space from some G7 rhetoric—were not abrupt shifts; they reflected a strategy designed to ensure a steady flow of fuel and maintain open connections. In education, this translates to a neutral stance in academic collaboration: maintaining relationships with both Israeli and Arab institutions, avoiding broad boycotts, publishing clear partnership criteria based on research ethics and human rights, and ensuring that visa, safety, and counseling services remain impartial. This is not an avoidance of moral responsibility; it is the best way to maintain academic connections when global tensions rise. It is also a form of protection: when one path closes, another can still be available for students and scholars.

A Practical Hedging Agenda for Education Leaders

The first pillar is to build energy resilience into financial planning. If utilities make up about 2 percent of a district's budget (a conservative assumption based on the $8 billion U.S. K-12 expenditure), a 15 percent efficiency gain or price hedge can free up 0.3 percent of total spending for education—often the deciding factor between cutting or retaining a program. This can be achieved through a combination of demand management, power purchase agreements (PPAs), targeted electrification, and efficiency upgrades. National energy offices emphasize that K-12 energy consumption is likely to increase without ongoing investments; federal programs are currently assisting schools in updating their HVAC systems. Districts are already taking action—one new geothermal and solar project in Massachusetts is expected to save around $300,000 annually.

The second pillar is planning for academic diplomacy. Ensure there are multiple options for student mobility and research opportunities so that no single channel—whether political or geographical—can disrupt access for students or influence grant funding. Identify MENA and Israeli partner institutions by academic discipline instead of politics, and maintain at least two active options in each critical field. Establish a consistent due diligence process that considers legal compliance, protection of human subjects, and conflict-of-interest concerns without becoming a sanctions regime. In moments of disruption—such as a sudden rise in oil prices on a Friday—activate automated support measures: emergency funding for students who face blocked remittance channels, flexible enrollment deadlines for those dealing with visa delays, and clear communication that separates campus safety from foreign policy. The strategic logic is similar to energy management: minimize risk of dependence on a single source. The geopolitical reasoning follows the example of Hormuz—if one route tightens, others can still accommodate traffic.

Education leaders are likely to face skepticism. Some may argue that energy management belongs with utility departments, not school administrations. Others may believe that taking a stand on academic partnerships could create problems. They may think budgets are too tight for this added complexity. However, the costs of inaction are very real. The World Bank's conflict scenarios demonstrate that inflation rises with oil prices; the IEA's June report highlights how quickly risk premiums can come back even in well-supplied markets. Research from Europe shows that gas and oil price shocks can have lasting effects on consumer prices. Every time this happens, districts and universities bear the burden unless they have planned for these risks. It is more affordable to build resilience during stable times than during crises. In a context where a single weekend's strike can shift price trends dramatically, "calm" is merely the period between major events.

What, then, is the required policy change? Stop viewing energy prices and international relationships as external factors and start treating them as integral to budgeting and partnerships. Implement oil price stress tests for budget proposals. Set minimum benchmarks for energy risk management at the campus level (from PPAs to peak load management). Publish principles for academic partnerships that enable collaboration across divides while adhering to core values. Tie international recruitment goals to diversified channels, including scholarships from the Gulf and research collaborations with Israel, ensuring that one political freeze does not disrupt incoming student groups. Add a simple note to every significant decision: how would a 10 percent rise in oil prices or a temporary closure of Hormuz impact costs or student opportunities? If that seems excessive, remember how much of Japan's oil supply comes from the Middle East and how quickly prices surged with the last missile strikes. Financial plans are easier to manage when they have already considered the tough questions.

We return to the opening fact because it underscores the stakes involved. When 95 percent of your crude comes from a region where 20 million barrels per day pass through a narrow strait, there is no barrier between foreign policy and schools. Japan's careful hedging this summer—criticizing some actions while promoting de-escalation and avoiding conflict with Washington—was not indecision. It was a strategy for survival for a democracy that relies on imports. The rest of us should learn from this approach. Build energy resilience into education finance during stable periods. Design academic diplomacy strong enough to withstand political storms. Keep pathways for student mobility open across political lines. And when the next geopolitical crisis arises, ensure that the calls from transportation or facilities in the morning are routine, not emergencies. This is not a weak policy; it is how to maintain education when the oil market trembles.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Anadolu Agency. (2025, June 14). Japan condemns Israeli attacks on Iran as “totally intolerable.”

Asahi Shimbun. (2025, June 24). Japan doesn’t criticize U.S. attack on Iran as it did Israel’s.

CTPost. (2025, Feb. 12). Stratford $133M school budget plan… electricity up more than 16%.

Federal Reserve Board. (2024, Aug. 2). Presno, I. Oil price shocks and inflation in a DSGE model of the global economy.

Higher Ed Dive. (2024, Dec. 16). College operating costs rose 3.4% in fiscal 2024 (HEPI).

IEA. (2025, June 13). IEA closely monitoring oil markets amid Israel–Iran situation.

IEA. (2025, June 17). Oil Market Report — June 2025.

IMF. (2024, Oct. 22). Commodity Special Feature: Price elasticities and inflation pass-through.

JASSO / Study in Japan. (2025, May 1). International Student Survey in Japan, 2024.

NASEO. (2024, Sept. 13). Energy-Efficient and Healthy K-12 Public School Facilities.

Nikkei Asia (via X). (2025, June 20). Japan distances itself from G7 statement on Israel–Iran conflict.

Nippon.com. (2025, June 9). Foreign students in Japan hit new record in 2024.

Reuters. (2025, June 23). Japan calls for de-escalation of Iran conflict.

Reuters. (2025, Sept. 18). Japan should diversify oil sources; 95% of crude now from Middle East.

StudyTravel / ICEF Monitor. (2025, May 6–7). Foreign enrolment in Japan reached record levels in 2024.

U.S. Department of Energy, Better Buildings. (n.d.). K-12 School Districts: $8B annual energy spend; second-largest expense after salaries.

U.S. DOE, Building Technologies Office. (n.d.). Efficient and Healthy Schools.

U.S. EIA. (2023, Nov. 21). Strait of Hormuz: world’s most important oil transit chokepoint.

U.S. EIA. (2025, June 16). In 2024, ~20 mb/d—about 20% of global petroleum liquids—transited Hormuz; flows steady in early 2025.

Washington Post. (2025, May 12). Schools are digging underground for their heat—and saving money (geothermal case).

World Bank. (2024, Apr. 25). Commodity Markets Outlook: conflict scenarios and inflation impact.

Comment