Stop Training Coders, Build Scientists: An ASEAN AI Talent Strategy

Published

Modified

Bootcamps produce tool users, not frontier researchers ASEAN needs a scientist-first AI talent strategy Fund PhDs, labs, and compute to invent, not import

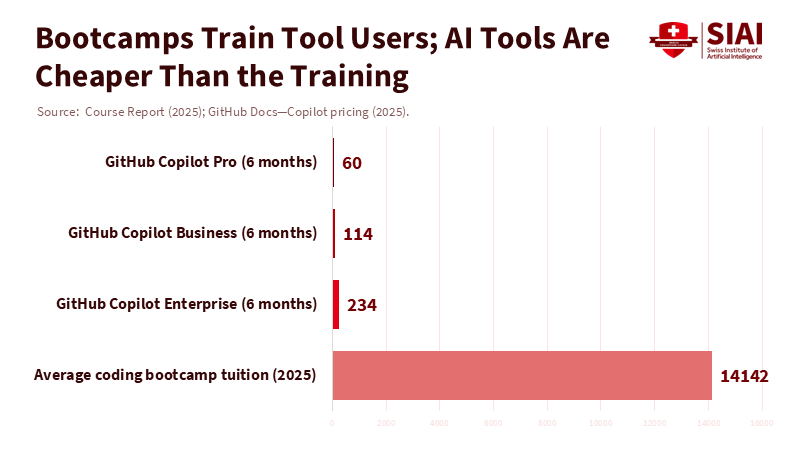

The statistic that should jolt us awake is simple: almost 40% of jobs worldwide will be affected by AI, either displaced or reshaped, according to the IMF. This scale of change is historic. It is not merely a coding-bootcamp issue; it is a problem of research capacity. If ASEAN opts for quick courses intended to help generalist software engineers use AI tools, the region risks repeating a mistake others have learned the hard way: preparing people to operate kits while leaving the science to others. The ASEAN AI talent strategy must start with a straightforward premise. Low-cost agents and copilots already handle much of what entry-level coders do, and their subscriptions cost less than a team lunch. If Southeast Asia wants to compete, it needs a pipeline of AI scientists capable of building models, designing algorithms, and publishing groundbreaking work that attracts investment and fosters clusters. This is the only approach that will scale.

Why an ASEAN AI talent strategy must reject “teach-everyone-to-code”

There is a common policy instinct: subsidize short courses that enable existing developers to utilize AI libraries from the cloud. This instinct is understandable. It is quick, appealing, and easy to measure. However, the market has evolved rapidly. Enterprise surveys in 2024–2025 indicate that the majority of firms are now incorporating generative AI into their workflows. Several studies report double-digit productivity gains for tasks like coding, writing, and support. Meanwhile, mainstream tools have lowered the cost of entry-level coding. GitHub Copilot plans run about US$10–$19 per user per month. OpenAI’s small models charge tokens at a rate of cents per million. When the marginal cost of junior tasks approaches zero, bootcamps that teach tool operation become a treadmill. They prepare people for jobs that machines can already perform. The ASEAN AI talent strategy must, therefore, focus on deep capability rather than superficial familiarity.

ASEAN’s higher-education and research base highlights the risk of remaining shallow. Several member states still report very low researcher densities by global standards. A recent review notes 81 researchers per million in the Philippines, 205 in Indonesia, and 115 in Vietnam—figures far below those of advanced economies. Malaysia allocates about 0.95% of GDP to R&D, roughly five times Vietnam’s share. Yet, even in Malaysia, the challenge is creating strong links between universities and industry. Suppose Southeast Asia spends limited resources on short training courses without enhancing research capacity. In that case, it will produce more users of foreign tools rather than scientists who develop ASEAN tools. That is a trap.

What South Korea’s bootcamps got wrong

South Korea serves as a warning. For years, policy emphasized rapid scaling of digital training through national platforms and intensive programs aimed at pushing more individuals into “AI-ready” roles. This approach improved literacy and awareness but did not create a surge of frontier researchers. Meanwhile, the political landscape changed. In December 2024, the National Assembly impeached the sitting president; in April 2025, the Constitutional Court removed him from office. The direction of tech policy shifted again. When strategy changes and budgets are adjusted, the only lasting asset is foundational capacity: graduate programs, labs, and a trained scientific base that can withstand disruptions. South Korea’s experience should caution ASEAN against equating bootcamp completion with scientific competitiveness.

There is also a harsh market reality. Employers are already replacing entry-level tasks with AI. A business leader survey conducted by the British Standards Institution in 2024–2025 reveals that firms are embracing automation, even as jobs change or vanish. An increasing number of studies show that copilots expedite routine coding, and some long-term data indicate a decline in junior placement rates at bootcamps compared to the pre-gen-AI era. None of this implies “don’t train.” It emphasizes the need to train for the right frontier. Teaching thousands to integrate existing APIs into apps will not provide a regional advantage when copilots perform the same tasks in seconds. Teaching a smaller number to design new learning architectures, optimize inference under tight energy budgets, or build multilingual evaluation suites will be challenging. That is what investors value.

China’s lesson: build scientists, not generalists

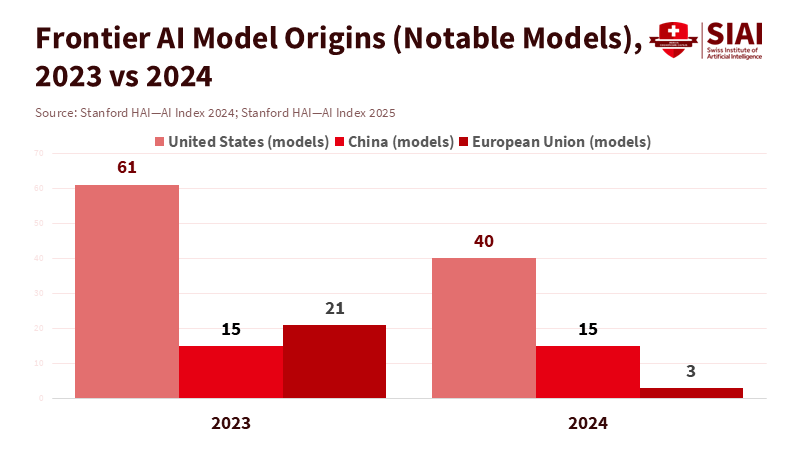

China’s current trajectory illustrates what sustained investment in talent and computing can achieve. In 2025, top universities increased enrollment in strategic fields such as AI, integrated circuits, and biomedicine to meet national priorities. Cities implemented compute-voucher programs that subsidized access to training clusters for smaller firms, transforming idle capacity into research output. China’s AI research workforce has grown significantly over the past decade, while its universities and labs continue to attract leading researchers. The United States still dominates the origin of “frontier” foundation models, according to the 2024 AI Index. Still, the global competition now revolves around who can build and retain scientific teams and who can obtain computing power at reasonable costs. The message for ASEAN is clear. To generate spillover benefits in your cities, invest in scientists and labs, not merely in users of tools. The research core is what anchors ecosystems and can lead to significant economic growth.

The talent strategy behind that research core is crucial. Elite programs attract top undergraduates into demanding, math-heavy tracks; they offer PhDs with generous stipends; they establish joint industry chairs allowing principal investigators to move between labs and startups; and they form groups that publish in competitive venues. The region doesn’t need to replicate China’s political economy to emulate its pipeline design. ASEAN can achieve this within a democratic framework by pooling resources and setting standards. The goal should be clear: train a few thousand AI scientists—people who can publish, review, and lead—rather than hundreds of thousands of tool operators. This is not elitist; it is practical in an age where entry-level work is being automated, and where rewards go to original research.

A regional blueprint for an ASEAN AI talent strategy

First, fund depth, not breadth. Create an ASEAN Doctoral Network in AI that offers joint PhDs across leading universities in Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Admit small cohorts based on merit, provide regional stipends tied to local living expenses, and guarantee computing time through a shared cluster. The backbone can be a federated compute alliance, located at research universities and connected through high-speed academic networks. Cities hosting nodes should ensure clean power; states should offer expedited visas for fellows and their families. Policymakers, your role is crucial in ensuring the success of this strategy. Success should not be measured by enrollment but by published papers, released code, and established labs.

Second, improve the research base. Most ASEAN members must increase their R&D spending and research intensity to move beyond applied integration. The gap is apparent. Malaysia allocates just under 1% of GDP for R&D, while some peers spend even less; several countries report researcher densities too low to support robust lab cultures. Establish national five-year minimums for public AI research funding. Tie grants to multi-institutional teams, ensuring at least one public university is involved outside the capital city. Encourage repatriation by offering packages for “returning scientists” that cover relocation, lab startup, and hiring of early-stage talent. A stronger research base will also lessen the need to import expertise at high costs.

Third, align policy with industry needs, but guard against dilution. Malaysia’s national AI office and Indonesia’s AI roadmap indicate intent to coordinate. Use these organizations to redirect funding toward fundamental research. Designate at least a quarter of public AI funding as contestable only with a university principal investigator on the grant. Require that every government-funded model provide a replicable evaluation card, complete with multilingual benchmarks that reflect Southeast Asia’s languages. This is how the region establishes credibility in venues where scientific reputations are built.

Fourth, support the early-career ladder even as copilots become more prevalent. The HBR warning is valid: if companies eliminate junior roles, they may jeopardize their future teams. Governments can encourage better practices without micromanaging hiring by linking R&D tax credits to paid research residencies for new graduates in approved labs. Provide matching funds for companies sponsoring PhD industrial fellowships. Promote open-source contributions from publicly funded work and establish national code registries that enable students to create portable portfolios. These small design choices can significantly impact career development.

Finally, acknowledge where generalist upskilling still fits. Digital literacy and short courses will remain crucial for the broader workforce, providing a buffer against disruption. However, they are not the foundation of competitive advantage in AI. The latest World Bank analysis for East Asia and the Pacific states that new technologies have, so far, supported employment. Yet, it cautions that reforms are needed to sustain job creation and limit inequality. ASEAN should benefit from gains while investing in the scarce asset: scientific talent capable of setting the frontier for regional firms. In a market with broad adoption, the advantage belongs to those who can invent.

We began with a stark statistic: 40% of jobs will be influenced by AI. The region can choose to react with more short courses or respond with a well-thought-out plan. The better option is a scientist-first ASEAN AI talent strategy that funds rigor, builds labs, secures computing power, and creates opportunities for researchers who can publish and innovate. Political landscapes will shift. Costs will drop. Tools will improve. What endures is capacity. If that capacity is rooted in ASEAN’s universities and companies, value will emerge. If it exists elsewhere, ASEAN will forever rely on renting it. The policy path is concrete. It requires leaders to choose a frontier and support it with funding, visas, computing power, and patience. Act now, and within five years, the region will produce its own research, not just consume press releases. Its firms will also hire the people behind the work. In a world filled with inexpensive agents, the only costly asset left is original thinking. Foster that.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aljazeera. (2024, December 14). South Korea National Assembly votes to impeach President Yoon Suk-yeol.

AP News. (2025, April 3–5). Yoon Suk Yeol removed as South Korea’s president over short-lived martial law.

British Standards Institution (BSI). (2024, September 18). Embrace AI tools even if some jobs change or are lost.

GitHub. (2024–2025). Plans and pricing for GitHub Copilot.

IMF—Georgieva, K. (2024, January 14). AI will transform the global economy. Let’s make sure it benefits humanity.

ILO. (2024). Asia-Pacific Employment and Social Outlook 2024.

McKinsey & Company. (2024, May 30). The state of AI in early 2024: GenAI adoption, use cases, and value.

OECD. (2025, June 23). Emerging divides in the transition to artificial intelligence.

OECD. (2025, July 8). Unlocking productivity with generative AI: Evidence from experimental studies.

Our World in Data (UIS via World Bank). (2025). Number of R&D researchers per million people (1996–2023).

Peng, S., et al. (2023). The Impact of AI on Developer Productivity. arXiv:2302.06590.

Reuters. (2025, March 10). China’s top universities expand enrolment to beef up capabilities in AI.

Reuters. (2025, July 22). Indonesia targets foreign investment with new AI roadmap, official says.

Stanford HAI. (2024). The 2024 AI Index Report.

Tom’s Hardware. (2025, September). China subsidizes AI computing with “compute vouchers.”

UNESCO. (2024, February 19). ASEAN stepping up its green and digital transition.

World Bank. (2025, June 17/July 1). Future Jobs: Robots, Artificial Intelligence, and Digital Platforms in East Asia and Pacific; Press release on technology and jobs in EAP.

World Bank/ASEAN (SEAMEO-RIHED). (2022). The State of Higher Education in Southeast Asia.