The Third Path in Asia-Pacific Security Economics: Keep Classrooms Open while States Harden

Input

Modified

Security and economics in Asia-Pacific have fused Alliances are uneven across the region Education must lead a balanced third path

Asia-Pacific security economics has shifted from a background issue to a driving force. It now influences visas, laboratories, and the types of jobs students prepare for. The scale of this change is significant. About 6.9 million students currently study outside their home countries, the largest group ever. When export rules or new security alliances change, these students feel the impact first. Their options can change overnight. Their supervisors may delay projects. Their degree plans may need to be altered. This trend began long before any elections in Washington. For years, policies across the region, from Tokyo to Manila to Hanoi, have combined economic goals with security objectives. This trend is strong and unlikely to reverse in the near future. The challenge is to ensure genuine security while maintaining open learning and research opportunities. This piece advocates for a third path—one that supports growth and encourages talent to remain engaged.

A fused reality in Asia-Pacific security economics

Clear developments mark the new order. In 2023, Japan joined the United States and the Netherlands in limiting exports of 23 types of chipmaking tools. Although the rules did not name specific target countries, they reshaped orders, lab plans, and vendor lists across the region. This policy aligns with Tokyo's broader security plans through fiscal year 2027, as outlined in strategic and budget documents from 2022. While analysts often compare this to a NATO-like "2% of GDP" benchmark, the government's documents provide a more nuanced perspective. The overarching message is clear: Japanese policy has made a structural shift. Universities and companies now consider security in procurement, hiring, and collaboration as a standard practice.

"Multilateral" agreements further strengthen this fusion. In April 2024, the leaders of the United States, Japan, and the Philippines announced the establishment of the Luzon Economic Corridor. This corridor connects ports, rail systems, digital networks, and training with deterrence and maritime cooperation. Meanwhile, the Philippines expanded U.S. access under EDCA to nine sites, including four new locations near key naval routes. These developments blur the lines between hard security and growth policies. They also shape how donors allocate funding for cables, underwater infrastructure, and skills training. In essence, capital and educational programs are now intertwined with security decisions. This is how Asia-Pacific security economics operates in practice.

China is viewing the situation through a similar lens. In October 2023, Beijing mandated the issuance of export permits for certain graphite products. The change was felt immediately in battery supply chains. China's international engagement remains extensive. In 2024, Belt and Road deals totaled approximately $121.8 billion in investments and construction contracts, with a growing focus on energy and technology. Central and Southeast Asia attracted significant flows. This approach combines statecraft with financial and industrial policy. It influences how universities design laboratories and how companies plan internships. The impact is regional, not confined to one country.

Uneven blocs—and the case for a third path

The geopolitical map is not uniform. Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines are closely aligned with the U.S. on security and technology. Taiwan's strength lies in semiconductors. In April 2024, the U.S. pledged up to $6.6 billion in CHIPS funding for TSMC's Arizona project, which plans to add a third fabrication facility and aims for 2-nanometer production. This approach combines industry policy with alliance management. It connects research programs, apprenticeships, and supplier networks across borders while also establishing stricter standards and regulations. These developments affect Asia's classrooms by shaping demand for skills in various fields, including materials science and AI hardware.

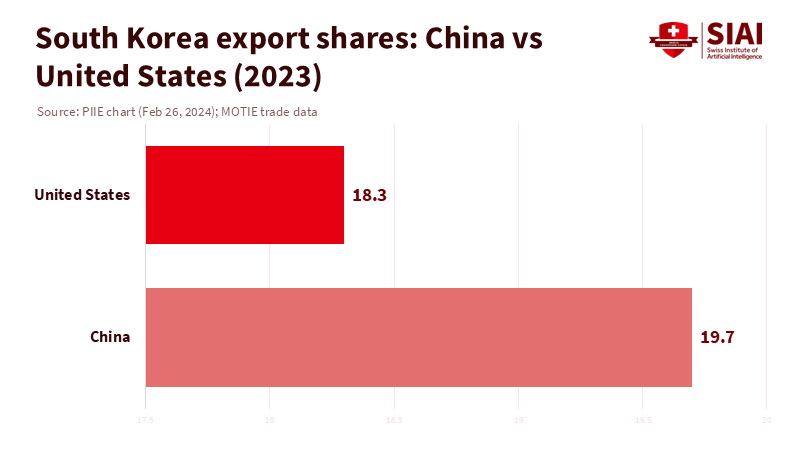

Vietnam and South Korea are taking a more cautious approach. Hanoi strengthened its ties with Washington in September 2023, establishing a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership that includes semiconductor ecosystem development and workforce training. The goal is clear: joint training and an expanded skills base. Seoul's trade patterns tell a related story. In 2023, China's share of Korean exports decreased to 19.7%, marking the first time in two decades that it fell below 20%. Meanwhile, the U.S. share rose to 18.3%, narrowing the gap to just 1.4 percentage points. This reflects an alignment of economics with security risk management, without severing ties completely. It is a process of reducing risk rather than decoupling, creating new talent pathways that bridge both systems.

Central Asian economies remain closely tied to China through energy, mining, and logistics. Belt and Road engagement surged again in 2024 and set new records in the first half of 2025, with Kazakhstan emerging as a top beneficiary. These financial flows direct educational programs toward extractive industries, grid management, and green energy technology. North Korea continues to align with China and Russia. The patterns of these blocs are deeply rooted, dating back long before 2025, and are unlikely to change soon. This is why a third path is essential. It aims to create safeguards that reduce risk without dismantling knowledge networks and provides students and researchers with stable avenues across different blocs.

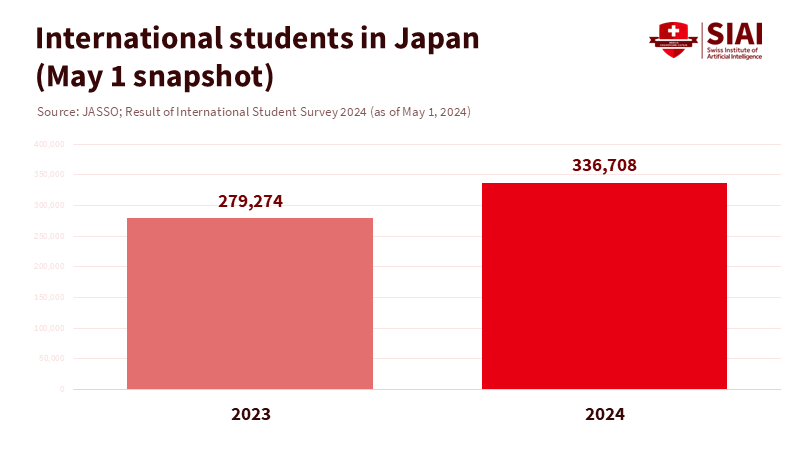

Why education must lead in Asia-Pacific security economics

Education is at the center of this system. It inspires people, sets standards, and transforms spending into skills. Unfortunately, it often becomes the first target when political tensions rise. Regional figures reveal both pressure and resilience. Australia recorded 925,905 international enrollments in July 2025, a slight decline from the previous year, despite higher education continuing to expand. Japan welcomed a record 336,708 international students as of May 1, 2024, marking a 21% increase from the previous year. In simple terms, the flow of students remains strong. However, it is shifting and now faces more exposure to security and technology regulations than ever before.

These regulations impact laboratories. Japanese and Dutch export controls on chip tools change what university clean rooms can purchase, maintain, or share. Chinese restrictions on graphite and related materials affect battery and materials programs. None of this outright bans cooperation; instead, it conditions it. This is a crucial distinction. Universities can still collaborate and train on a large scale. Still, they need governance that anticipates licensing, data protection, and compliance with standards from the start. If not, companies may relocate training to places with fewer restrictions. This would weaken the region's human capital advantage, and we should prevent that.

The broader context remains encouraging if we establish the proper rules. Global academic mobility has reached record levels. UNESCO reports around 6.9 million students studying abroad. The issue is not a lack of demand; the problem is friction. Visa clarity, equipment licensing, and reliable data systems dictate where students choose to study and where laboratories are built. This is Asia-Pacific security economics at work in education. Policymakers can reduce friction without lowering security standards. Striking this balance requires education leaders to be actively involved in the decision-making process, rather than just observers.

Designing the third path

The third path is straightforward in its goal but complex in execution. It protects essential security interests while maintaining open channels for education and research. Begin with risk segmentation. Not all cross-border activities carry the same level of risk. Some fields involve dual-use technology and require strict controls, while others are low-risk and should be expedited. A one-size-fits-all approach creates slowdowns and encourages companies to shift training activities away from the region. A tiered model maintains trust where the risk is highest and facilitates talent movement where the risk is low.

Next, establish effective structures. The Luzon Corridor demonstrates how transportation, data flow, and skills can be integrated with strategy. We need similar frameworks for research. Standard clauses for data security, export-control compliance, and open science can be incorporated into every joint degree and lab agreement. This would lower legal expenses and speed up approvals, providing regulators with more transparent oversight. For students, similar practices should be adopted. Publish visa service standards for priority programs and establish post-study work rules that align with labor needs in chip manufacturing, energy, and health. Combine this with yearly capacity reviews to allow for necessary adjustments. The goal is to transform uncertainty into rules that people can plan around.

Talent finance should align with the new landscape. The U.S.–TSMC agreement links manufacturing to training and local supply chains. Vietnam's Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with the United States launched funding for a semiconductor workforce. These models can be expanded regionally through co-funded scholarships, apprenticeship visas, and joint courses in high-demand fields. The underlying principle remains the same: develop skills where factories and laboratories will be located. Keep avenues open for partners who comply with the rules. This approach balances security with growth.

Honest language is also crucial. The goal is to reduce risk, not to decouple from it. Korea's export shares illustrate how a major economy can adjust its export patterns without breaking ties. China's graphite export permits and Japan's tool restrictions demonstrate how countries can target specific vulnerabilities. Education policy should reflect this precision: protect the few dual-use points carefully while maintaining an open, broader system. This strategy preserves innovation, spreads standards, and keeps the region's economic engine running smoothly while fostering peace through shared interests across borders.

The decisions made in the region over the next five years will shape a generation of outcomes. Asia-Pacific security economics is a lasting reality. It existed before any single leader or tariff choice and connects capital with strategy and classrooms. Rather than resist this reality, we should work to shape it. The third path proposes clear rules, strategic segmentation, and investments in skills where they are most needed. It safeguards security without closing off minds or borders. It transforms friction into predictability and talent loss into opportunities for talent. The stakes are high, and if we get it right, the rewards will be substantial. The 6.9 million students currently on the move—and the many more to come—depend on it, as do the businesses and laboratories that will employ them.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Australian Government Department of Education. (2025). International student monthly summary and data tables.

Biden–Harris Administration / National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2024, April 8). Biden-Harris Administration announces preliminary terms with TSMC, expanded investment.

Brookings Institution. (2023, May 22). No, Japan is not planning to “double its defense budget.”

Japan Ministry of Defense. (2022). Defense programs and budget of Japan (FY2022).

Japan–U.S.–Philippines Leaders. (2024, April 11). Joint vision statement—Luzon Economic Corridor. The White House.

Japan–U.S.–Philippines. (2024, April 11). Fact sheet: Celebrating the strength of the U.S.–Philippines alliance. The White House.

Japan–U.S. export controls. (2023, July 24). As Japan aligns with U.S. chip curbs on China… Reuters.

Japan export controls on chipmaking equipment. (2023, March 31). Reuters.

JASSO / Study in Japan. (2025). Result of International Student Survey in Japan, 2024 (as of May 1 2024).

Philippines–U.S. EDCA. (2023, April 3). New EDCA sites named in the Philippines. U.S. Department of Defense.

PIIE (Peterson Institute for International Economics). (2024, February 26). South Korea’s exports to the United States and Japan overtook exports to China in 2023.

PIIE / RealTime Economics. (2024, January 26). Is South Korea de-risking?

Reuters. (2023, October 20). China curbs graphite exports in latest critical minerals squeeze.

The White House. (2024, April 8). Statement from President Joe Biden on CHIPS and Science Act preliminary agreement with TSMC. TSMC Arizona. (2024, April 8). TSMC Arizona and U.S. Department of Commerce announce up to US$6.6 billion in proposed CHIPS Act direct funding.

UNESCO. (2025, June 24). Record number of higher education students highlights global need for recognition of qualifications.

UN–Griffith Asia Institute / Green Finance & Development Center. (2025, February 27). China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2024.

U.S.–Vietnam Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. (2023, Sept. 10–11). Joint leaders’ statement / Fact sheet: Semiconductor workforce initiatives. The White House.