Europe’s Productivity Gap Is a TFP Problem, Not Capital

Input

Modified

Europe isn’t short on capital or degrees; it’s short on TFP The fix is leadership that scales tech, intangibles, and management practice Educators, policymakers, and CEOs should fund intangibles and integrate AI in SME training

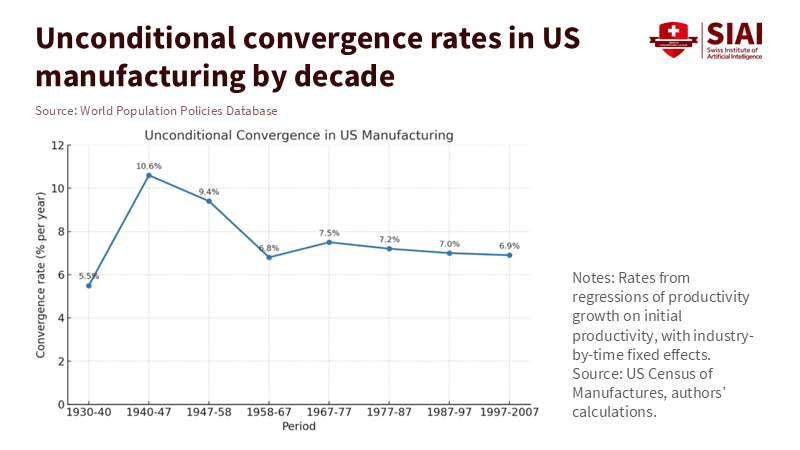

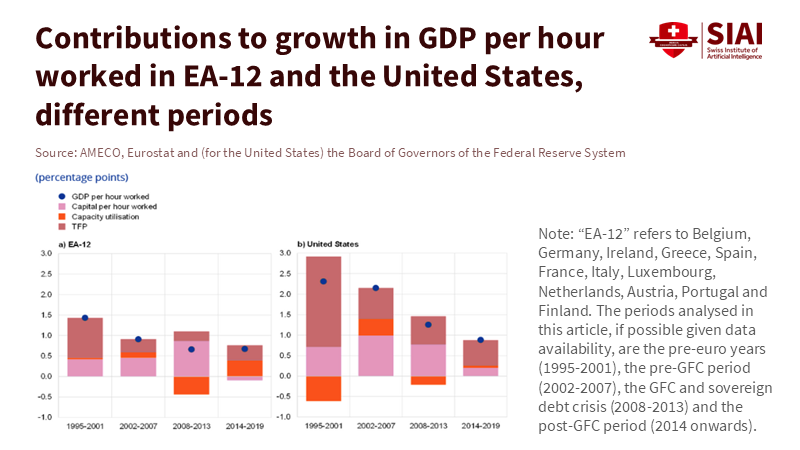

One number explains why the EU productivity gap with the United States persists. Since the mid-1990s, total factor productivity (TFP) has accounted for approximately 60% of labor productivity growth in the EU. However, its contribution has gradually declined—from roughly two-thirds in the late 1990s to just over half in the 2010s. When the main engine for productivity gains falters, even substantial investments in capital and improvements in education can't close the gap. Recent comparisons show that the euro area's TFP contribution to hourly productivity was nearly zero during the 2010s. At the same time, the United States consistently reported positive contributions. In 2023–24, this trend largely continued. Europe invests approximately 21% of its GDP in fixed capital. It has increased tertiary degree attainment among 25–34-year-olds to 43–44%, yet GDP per hour remains significantly lower than in the U.S. The issue is not a lack of money or degrees. It lies in how well leadership—both public and private—transforms capital and labor into cutting-edge technology and effective organization (TFP) on a large scale. This is a policy choice, not a fixed outcome.

Leadership Turns K + L into TFP

The three factors of growth economics—capital, technology, and labor—are not equally effective in practice. Investing in capital increases output temporarily, while enhancing human capital raises the potential ceiling for future growth. However, only TFP drives how companies combine capital and skills, through the adoption of cutting-edge technologies and modern management practices. The data indicate that, across advanced economies, long-term differences in productivity growth are primarily driven by variations in the diffusion of technology, organizational quality, and investment in intangible assets. In EU data, capital deepening, including ICT, contributes to hourly productivity growth. Still, the sharp decline in TFP has been a significant factor in the gap with the U.S. since the mid-2000s. Simply put, Europe's inputs are respectable, but its ability to turn those inputs into value is lacking.

From this perspective, promoting solid industry leadership isn't just a cultural appeal; it involves serious institutional efforts to create integrated markets that reward scale, support intangible asset funding, and teach the practices needed to make technology effective. Europe has plenty of engineers and machines, but it lacks rapid diffusion. For instance, in 2023, 45.2% of EU businesses purchased cloud services (an increase of 4.2 points from 2021), yet only 8% utilized any AI technology. By 2024, AI usage rose to 13.5%, still far from the target of "three in four firms" set for 2030. Firms that lag are not just lacking tools; they also lack established processes, data management, and practices that enable teams to rethink their workflows. Those are decisions made by leadership.

Evidence: The EU Productivity Gap Is About Diffusion, Not Supply

Let's start with the inputs. In terms of human capital, Europe has made significant progress. By 2023, 43% of EU 25–34-year-olds held tertiary degrees, and this increased to 44.2% in 2024, nearing the 45% target for 2030. Regarding investment, the EU's gross fixed capital formation was approximately 21.2% of GDP in 2024, nearly identical to the euro-area average and comparable to the U.S. percentage in recent years. If the issue lay solely with inputs, we would expect much quicker convergence. However, that is not happening.

Now, consider hourly output and TFP contributions. The Conference Board's 2024 summary indicates that Europe and the euro area are lagging behind the U.S. in productivity levels. The U.S. TFP has provided steady support for hourly output growth since 2011. In contrast, the euro-area TFP has remained around zero or slightly positive for most of the time. This isn't just a temporary cycle; it's a structural alert. When the growth aspect, which reflects how effectively firms operate and how quickly they learn, stagnates, more capital or education alone won't improve long-term productivity.

Two structural factors primarily drive the gap. First, investment in intangibles—such as software, data, brands, design, and organizational capital—remains a smaller portion of total investment in the EU compared to the United States. A detailed analysis from 2024 reveals that the U.S. allocates significantly more to "other intellectual property products" (approximately 5% of gross fixed capital formation). In contrast, the EU27 contributes less than 1%. Even for R&D, the U.S. surpasses the EU's share, especially when excluding the effects of multinational corporations in Ireland. Intangibles fuel TFP, and underfunding them slows both adoption and diffusion.

Second, market integration and financing are inconsistent. The IMF's 2024–25 report on Europe's productivity highlights fragmentation and underscaling as major obstacles. Emerging high-growth firms face limited cross-border opportunities and a smaller, less risk-taking venture ecosystem compared to the U.S. The ECB also notes that euro-area business investment, particularly in intangible assets and AI-related ICT, has lagged behind the U.S. since 2021. The mix of industrial R&D remains focused on established sectors (autos, equipment) rather than digital platforms and data-rich services. The policy implication is straightforward: creating a Capital Markets Union and a more integrated Single Market for services is not merely an abstract discussion; they are essential to boosting TFP.

Data on technology adoption underscores the same point. AI represents the latest general-purpose technology. In 2023, only 8% of EU companies used it; the increase to 13.5% in 2024 is promising but still highlights a significant diffusion gap, particularly among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Cloud adoption is better, yet uneven: nearly half of firms purchase cloud services, but advanced or intermediate use remains around 39%. Meanwhile, the U.S. leads in creating cutting-edge AI models and in attracting AI investments, reflecting the strength of the broader innovation ecosystem from which Europe's firms ultimately benefit.

What do educators and policymakers must do now?

If the main issue is poor diffusion and weak leadership, education policy plays a central role in the solution. Universities and vocational systems need to train not only coders and engineers but also technology managers—people who can redesign processes, oversee data, and coordinate cross-functional teams. Research shows that when firms implement basic operational practices—such as quality control, performance monitoring, and lean routines—productivity improves, and these effects persist over time. Europe should incorporate these practices into business schools, engineering courses, and apprenticeship programs, including capstone projects that require teams to apply, rather than merely discuss, AI and data-driven tools in real business settings.

Regional diffusion institutions are as important as degrees. The U.S. has long supported the National Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) to provide management expertise and digital tools to small and medium-sized businesses. Europe has begun to establish a similar network with European Digital Innovation Hubs (EDIHs), which now comprise over 160 centers across all Member States and several associated countries. The next step is to focus and expand: align EDIHs with sector-specific clusters, set clear adoption targets (like the percentage of SMEs using AI in at least one workflow), and tie public support to measurable improvements in productivity and export performance.

Support the shift toward intangible investments. Public incentives currently favor physical assets over software, data, and intangible assets such as organizational capital. Tax and grant programs should be adjusted to prioritize investments in software modernization, data platforms, cybersecurity, and process re-engineering. The European Investment Bank and national promotional banks can take the lead with standardized "intangible investment loans." At the same time, the EU is developing cross-border venture funding to support businesses in their growth stages. Evidence indicates that Europe's share of intangible investments is lower than that of the U.S.; addressing this imbalance is the most effective way to boost TFP without waiting for demographic shifts or changes in energy prices.

Make the Single Market for skills and services a reality for schools and businesses. Recognizing micro-credentials in data, AI safety, cloud, and operations would enable universities and training providers to serve a truly European student population. Education ministries should support "AI-in-curriculum" programs that help faculties redesign assessment, feedback, and project work around reliable AI tools, ensuring graduates are fluent in real-world technology stacks. Because diffusion struggles in smaller firms, governments could jointly purchase enterprise licenses for SMEs through regional groups, reducing adoption costs while establishing common data and security standards.

Close the EU Productivity Gap by Making TFP the Leadership Metric

Prepare for and address three common critiques. First, "we just need more investment." That's true, but composition matters: since 2021, U.S. business investment—especially in intangibles connected to AI and data centers—has exceeded that of the euro area, while EU R&D still focuses on traditional sectors. More machines without updated workflows represent wasted resources. Second, "we already have the Single Market." That's the case for goods, mostly; however, in services, data, and finance, we have work to do. Fragmentation is precisely what the IMF and ECB identify as a TFP barrier. Third, "AI adoption will happen naturally." The increase in 2024 is positive, but diffusion isn't automatic. It relies on practical management training, interoperable data, and patient capital. You might call it "boring leadership," but it pays off in the long run.

Europe should evaluate progress using the one measure that truly counts for convergence: firm-level TFP. This means regularly publishing comparable indicators for intangible investment, management quality, and technology use, separated by firm size and region. These indicators should influence funding for higher education and regional development; public procurement should be connected to evidence of technology adoption among suppliers. Schools and universities should also be given the freedom—and pressure—to redirect resources toward the challenging but essential tasks of redesigning processes and managing data.

TFP accounts for a significant portion of Europe's productivity growth, and its contribution has been decreasing. The risk is clear. When TFP stagnates, GDP per hour stagnates, wages stagnate, and political confidence wanes. The solution is equally clear. Treat TFP as a leadership metric and shape policy around diffusion, supporting intangible investments, enhancing cross-border financing, embedding management practices in education, and holding institutions accountable to specific adoption targets. In the 20th century, late-industrializers caught up by combining capital growth with continuous organizational learning. In the 21st century, those who can effectively turn cloud technology, data, and AI into everyday practices will define Europe's growth trajectory. We do not lack capital or talent; we lack the determination to convert both into productivity rapidly. This is the urgent call to action for ministers, deans, and CEOs—because TFP is not a mystery; it reflects the results of effective leadership.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Conference Board (2024). Total Economy Database™: Summary Tables & Charts (May 2024). New York: The Conference Board. (Charts 3A–3B, 4, 5).

ECB (2021). Economic Bulletin 7/2021. Frankfurt: European Central Bank. ("Drivers of labor productivity in the euro area since the mid-1990s," Chart 2).

ECB (2025). "Business investment: why is the euro area lagging behind the United States?" Economic Bulletin Focus Boxes. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

EIB (2024). Dynamics of Productive Investment and Gaps between the EU and the United States. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, Working Paper 2024/01.

EC (2024). Towards Digital Decade targets for Europe. Eurostat Statistics Explained.

Eurostat (2023–2025). Cloud computing—statistics on the use by enterprises; Digital economy and society statistics—enterprises; Use of AI in enterprises. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Eurostat (2024–2025). Educational attainment statistics; 43% of EU 25–34 with tertiary education (2023); 44.2% (2024). Luxembourg: Eurostat.

IMF (2024–2025). Europe's Productivity Weakness—Firm-Level Roots and Cross-Border Constraints. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

OECD (2024). Digital Economy Outlook 2024 (Vol. 1). Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2025). The Adoption of Artificial Intelligence in Firms. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Stanford HAI (2025). AI Index Report 2025. Stanford: Human-Centered AI Institute.

World Bank & Researchers (Bloom et al.). (2013; 2018). "Does Management Matter? Evidence from India," and "Do Management Interventions Last?" QJE and NBER Working Paper 24249.

European Commission (2025). European Digital Innovation Hubs (EDIH) Network—Activities and Impact. Brussels: DG CONNECT/JRC updates.

Comment