Upstream of CPI: Teaching the Economy We Read Before We Measure

Input

Modified

News text is upstream of inflation: it shapes expectations before numbers move Text-based indicators and the “rumour vs news” spread improve nowcasts and link commodity narratives to market prices Educators and policymakers should build curricula and communications that read, measure, and act on text at scale

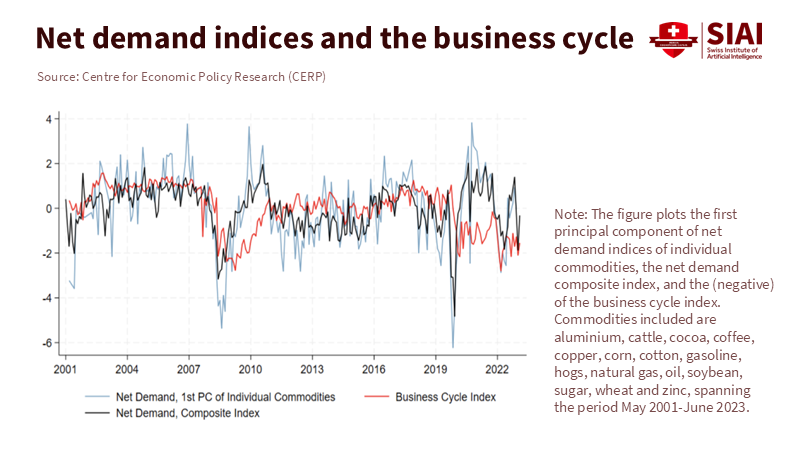

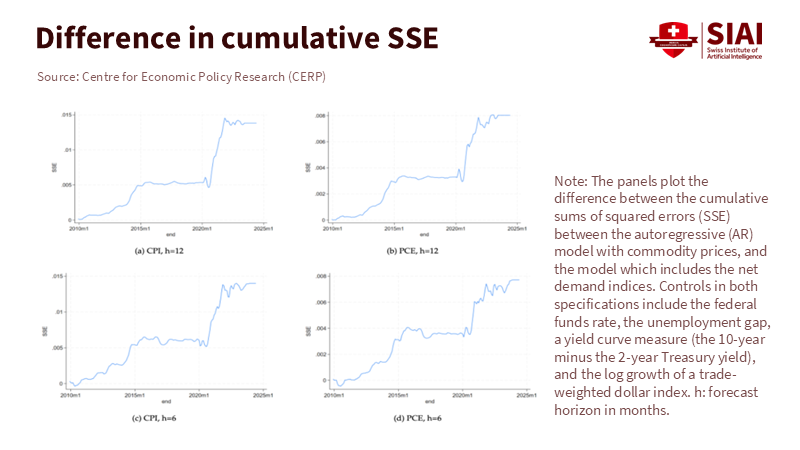

One statistic should worry anyone who thinks inflation is just numbers. Researchers created text-based indicators of supply and demand shocks from over a million business news articles. Their models reduced inflation forecast errors by 20 to 30% compared to standard predictors. This is not a minor adjustment; it shows that the economic story people read often changes before the numbers catch up. If signals from news about diesel inventories, port strikes, and grain corridors can refine our expectations about prices, then teaching and policy that wait for quarterly data are starting too late. The main point is clear: we can look upstream—into the text that shapes expectations—rather than just relying on realized data. Once we treat news as data, the old trader’s saying, “buy the rumour, sell the news,” shifts from folklore to a guide on how expectations turn into prices.

We expand on this idea in two ways. First, text is not just another variable to throw into a regression; it is where expectations are formed, coordinated, and contested in real time. Reading news provides households and firms with insights about what matters, how quickly it is changing, and how confident others are about it. Second, since expectations drive consumption and investment choices, news that shapes inflation expectations also influences equity markets. You won’t find a direct link between CPI and stock returns, but both hinge on future beliefs. The mistake in policy and teaching is to treat news as noise that must be adjusted for through lagging data. In reality, numbers often reflect what text has already made clear.

This upstream perspective clarifies another issue: the “text to number” conversion we rely on—waiting for prices and summarizing them—introduces its own noise. When we quantify textual shocks directly, we can partially avoid this conversion loss. Central banks and researchers have begun to do this, building daily news-sentiment indexes, training models on commodity narratives, and encoding communications to extract future signals. For schools, research centers, and government ministries, this means training students and analysts to work with text effectively—cleanly, consistently, and with transparent notes—providing them with a timelier view of behavior that later shows up in the data.

Upstream Data, Downstream Behavior

If news sets expectations, we should see this reflected in the measurement of expectations. We do. In mid-2025, U.S. one-year-ahead median inflation expectations remained around 3.1 to 3.2% in the New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations, while three-year and five-year expectations were about 3.0% and 2.9%. University of Michigan readings showed a similar pattern of stubborn expectations and a fragile mood. By late August 2025, the headline sentiment index dropped to 58.2, with long-term inflation expectations higher than before the pandemic. The key takeaway is not whether the level is high or low, but that these surveys reflect what people think after they read, hear, and discuss prices—a process primarily influenced by news. When those expectations shift, consumption and wage negotiations shift too, well before the following CPI report is released.

Attention amplifies this effect. Households and markets do not treat every headline the same; during high-inflation periods, they pay more attention to price news and react more intensely. Recent studies quantify an “attention threshold”: when inflation becomes prominent, asset prices and survey responses become more responsive to inflation news. This means that when inflation is a significant concern, people and markets pay more attention to news about inflation, and their reactions to such news become more pronounced. This explains why a surge in coverage about shipping costs or energy outages can influence both expectations and immediate pricing decisions. It also highlights why central banks are using text analytics: if news impact varies with the situation, using text for current insights becomes essential. At the same time, policy institutions have started to encode their communications (press conference statements, minutes) to enhance core inflation forecasts and to pilot AI tools that analyze qualitative PMI comments to improve growth predictions. The message is clear: reading comes before measuring.

Rumour, News, and the Inflation–Equity Channel

“Buy the rumour, sell the news” is often seen as a trading saying; in truth, it captures a broader principle. When information is uncertain but directional—like rumours of an OPEC production cut or an impending rail strike—investors take positions based on those possibilities. When the official news arrives, prices may drop or stabilize because the expectation has already affected the market. Extensive research shows that media tone and pre-announcement information influence returns; earlier studies using Wall Street Journal columns demonstrated that negative-tone days lead to lower, mean-reverting next-day returns. Recent work also indicates that rumours correspond with significant pre-publication price movements, while official announcements trigger uneven price shifts. This doesn’t mean that rumours are always correct; it shows that markets incorporate textual signals into prices ahead of time.

This principle also applies to inflation. Specific narratives about commodities—such as reopened ports, poor harvests, and refinery outages—spread quickly through news and social media, influence expectations, and alter hedging and inventory decisions. In 2023, as the Bloomberg Commodity Index declined by about 7.9% after two years of inflation, inflation eased; however, the prominence of price stories remained high, and the attention channel remained open. When text-based commodity shock indicators reduce inflation forecast errors by up to 30%, they are likely capturing expectations forming in language, revealing themselves first in asset prices, and only later becoming official inflation numbers. Think of equity and credit markets as the rapid reflection of those expectations; the difference between rumour and news is not noise but a valuable insight for a macro approach focused on expectations.

A practical research program can be designed. Create a “rumour–news spread” by analyzing pre-announcement price changes around events likely to affect inflation (like OPEC meetings, crop reports, and labor votes) and compare that to adjustments after announcements. Combine this with text-derived indices from commodity coverage and daily news-sentiment series. Estimate how much of next month’s core goods and energy inflation can be predicted by changes in (i) the text index and (ii) the spread. A brief method note is sufficient: train a supervised classifier on labeled news to distinguish supply from demand narratives; aggregate to weekly scores; feed them into a simple model with survey expectations and policy rates. The hypothesis—consistent with existing findings—is that including the rumour–news spread and the commodity-text index will reduce prediction errors and help distinguish quickly moving shocks (expectations) from slowly moving ones (contracts).

How Education Systems Should Respond Now

For educators, the shift in curriculum is overdue. We need to teach students to treat text as essential data for macroeconomics, finance, and policy. This includes creating “expectations labs” where students gather, clean, and categorize articles about energy, freight, and food; reproduce basic news-sentiment indexes; and connect those series to survey expectations and near-term inflation. It also involves teaching carefulness: lexicons and embeddings can misrepresent mood; labels can reveal hindsight. Assignments should require clear method notes—such as how articles were selected, how models were tested, and how results were interpreted—so that writing does not disguise itself as proof. The benefit is not only technical skills. It creates a discipline of reading that helps future analysts understand which stories influence behavior and why specific phrases (“temporary bottlenecks,” “broad-based pressures,” “sustained disinflation”) impact how companies set prices or when households make big purchases. Central banks experiment with AI and text, showing that these skills are becoming necessary.

For administrators managing programs and research centers, the investments are modest and the returns significant. Open-source NLP tools and public data (from official surveys to daily news-sentiment series) make it possible to conduct live forecasting exercises in classes and policy clinics. Collaborations with statistical agencies and central banks can provide anonymized text collections or commentary feeds with straightforward data-use agreements. Governance is essential: instructors should establish review protocols to separate model creation from policy conclusions, requiring out-of-sample performance before claims are included in memoranda. The aim is not to chase every headline; it is to find out if adding text improves predictions and narrative discipline. Where it does—as recent work with AI on central bank communications and PMI comments indicates—students can document the improvement, replicate it, and explain it. Where it does not, they can illustrate why.

For policymakers, communication is a part of policy. Research shows that when inflation is prominent, attention increases, and the same news influences behavior more significantly. This requires clear, consistent, and forward-thinking communication—especially when underlying stories shift from supply to demand and back. It also means considering rumours as early signals rather than mere nuisances. If a rumour realistically predicts a policy-relevant event, officials can address misleading claims while recognizing fundamental uncertainty, reducing the chances of sudden reactions that later impact prices and wages. Evidence that improved central bank statements enhance core inflation forecasts suggests another step: making those statements more predictable in structure and language so that both models and people can identify the signal. Additionally, direct communication may help shape expectations among specific audiences. In a world where text is upstream, credibility is built word by word.

None of this ignores the risks. Text can be messy, politicized, and easily misinterpreted. Models sensitive to rumours may overreact to coordinated noise. The tone of the news can reflect past movements instead of future trends. Therefore, in teaching and policy, the safeguard is triangulation, not overconfidence: combine text with surveys, market indicators, and inventories; compare models across different countries and contexts; and clarify uncertainty instead of hiding it in adjectives. A small method note can make a big difference: when solid numbers are lacking, show your assumptions and ranges, and justify them with observable factors—procurement cycles, shipping schedules, planting calendars—that relate to the words.

The classroom version of “buy the rumour, sell the news” is not a bold playbook; it is a reminder that narratives drive our economy. Once a widely read outlet presents a commodity disruption as demand-driven rather than supply-driven, firms with slim margins and households living paycheck to paycheck adjust. Some raise prices or speed up purchases; others adjust their investments, affecting financing costs and investment plans. The rumour channels the possibility; the news defines the uncertainty; the data reflects it later. Teaching students and analysts to follow that progression—with carefulness and clear writing—is the most valuable lesson about inflation we can provide.

Returning to the initial fact: a text-driven model that reduces forecast errors by up to one-third indicates that much of what we need to know about inflation shows up in language before it can be measured in prices. The challenge for education systems and policy offices is to make this insight a standard practice. Build the pipelines, teach people to read effectively, and acknowledge uncertainty. If we do this, we won’t just improve inflation predictions. We will bridge the gap between what people read, what they anticipate, and what decisions we make—making the next inflation surprise more manageable and solvable, and less of a shock.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Araujo, D. K. G., et al. (2025). Embedding central bank communications for inflation prediction. BIS Working Paper No. 1253.

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. J. (n.d.). Economic Policy Uncertainty Index (methodology and data).

Bloomberg (2024). Indices 2024 outlook: Global commodities. Bloomberg Professional Insights.

Bloomberg (2025). Commodities 2025 outlook. Bloomberg Professional Insights.

Brunnermeier, M. K. (2000/2001). Buy on rumours, sell on news (working papers). Princeton University.

Cleveland Fed (Pfäuti, O.) (2024). The Inflation Attention Threshold and Inflation Surges (slides).

Cornell Chronicle (2016). The nuances of “buy the rumour, sell the news”.

DIW Berlin via Reuters (2025). AI raises accuracy in predicting ECB moves.

ECB (2024). Artificial intelligence: a central bank’s view (speech).

ECB (2025). ECB visitors – can direct communication alter inflation expectations? (blog).

ECB Working Paper No. 3047 (2025). Word2Prices: embedding ECB statements improves core-inflation forecasts.

FRBSF (2020–). Daily News Sentiment Index (data and methodology).

IG (2019). “Buy the rumour, sell the news” explained.

Malliaropoulos, D., Passari, E., & Petroulakis, F. (2024). Text-based commodity disturbances and inflation forecasting (Working Paper). Bank of Greece.

New York Fed (2024–2025). Survey of Consumer Expectations (news releases).

Tetlock, P. C. (2007). Giving Content to Investor Sentiment: The Role of Media in the Stock Market. Journal of Finance.

University of Michigan (2025). Surveys of Consumers (press releases and tables).

VoxEU/CEPR (2025). Understanding inflation with textual analysis: How news about commodities improves predictions.

Zhang, W., et al. (2024). Rumors and price efficiency in stock markets. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance.