Borderless AI Labor Is Changing Work and School

Published

Modified

AI is making labor borderless as online services surge Opportunity expands, but standards, audits, and broadband are crucial Schools must teach task-first skills, platform literacy, and safeguards

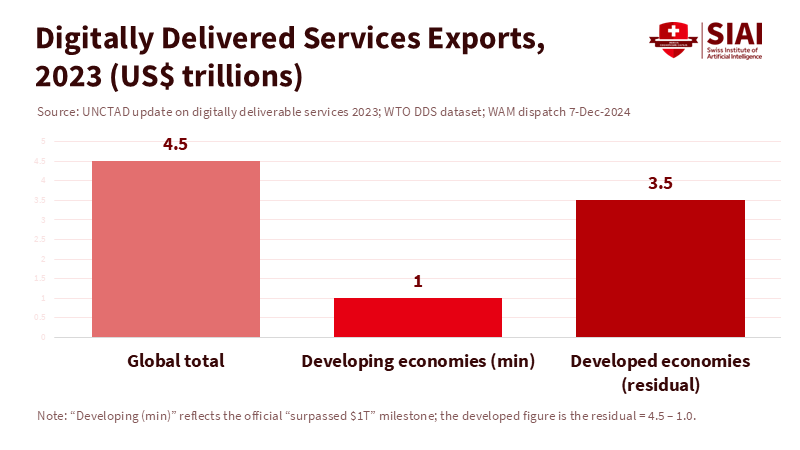

The fastest-growing part of global trade is undergoing a profound transformation. In 2023, digitally deliverable services—work sent and received through networks—reached about $4.5 trillion. For the first time, developing economies surpassed $1 trillion in exports. This accounts for more than half of all services trade. Borders still exist, but for more tasks, they function like dimmer switches rather than walls. This is the world of borderless AI labor, a transformative force where millions of people annotate data, moderate content, build software, translate, advise, and teach from anywhere. The rise of large language models and affordable coordination tools has accelerated this shift. Employers can now swiftly create distributed teams, manage them with algorithmic systems, and pay them across time zones. The key question is not whether jobs will shift, but who sets the rules for that shift and how schools and governments prepare people to succeed in it.

The borderless AI labor market is here

The numbers clearly illustrate this trend. In a 2025 survey of employers, 40-41% of firms indicated they would reduce staff where AI automates tasks. At the same time, they are reorienting their business models around AI and hiring for new skills. This change does not spell disaster. By 2030, the best estimate is a net gain of 78 million jobs globally, with 170 million created and 92 million displaced. To put it another way: tasks are moving, talent strategies are changing, and opportunities are opening—often across borders. The borderless AI labor market is not just a shift, but a gateway to unprecedented growth and opportunity.

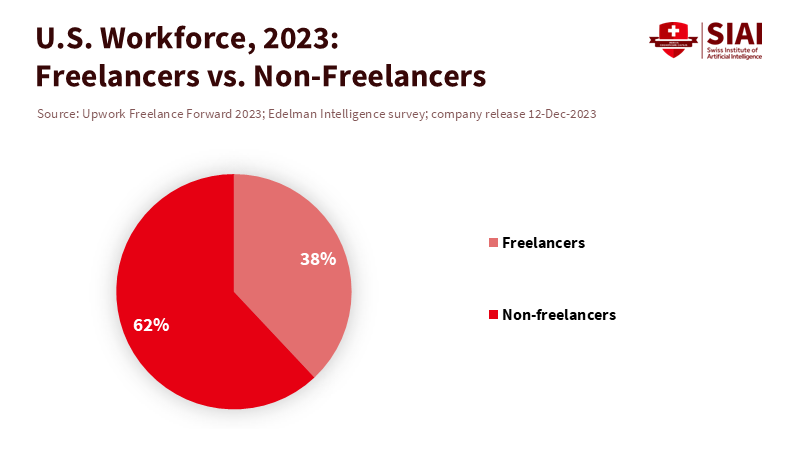

Hiring practices are already reflecting this shift. Data from platforms show that remote and cross-border hiring increased through 2024. Over 80% of roles on one global platform were classified as remote, and cross-border hiring rose by about 42% year-over-year. In the United States alone, 64 million people—or 38% of the workforce—freelanced in 2023, many serving clients they never met in person. These trends, coupled with the surge in digitally delivered services, confirm that borderless AI labor has scale and momentum.

Winners and risks in borderless AI labor

The benefits are significant. For the 2 billion people in informal work—over 60% of workers in much of the Global South—AI-enabled matching, translation, and reputation tools can help clarify skills for employers and create opportunities for higher-value tasks. This is the inclusive promise of borderless AI labor, where visibility and trust are essential in global services. When communication, payments, and rating systems are tied to the worker, location becomes less critical, and performance issues become more significant.

However, the risks are real and immediate. The global supply chain for AI, which relies on data labelers and content moderators in cities like Nairobi, Manila, Accra, Bogotá, and others, is a key part of this issue. Over the past two years, research and litigation have highlighted issues like psychological harm, low pay, and unclear practices within this ecosystem. New projects by policy groups are beginning to show how moderation systems can fail in non-English contexts and low-resource languages. The solution is not to withdraw from global work but to set enforceable standards for wages, safety, and mental health support wherever moderation and annotation take place. While automation can filter some content, it cannot replace the need for decent labor conditions.

A subtler risk comes from algorithmic management itself. This refers to the use of AI tools to assign tasks, monitor productivity, and evaluate workers at scale. Recent surveys in advanced economies reveal widespread use of these systems and varied governance. Many companies have policies, but many workers still express concerns about transparency and fairness. In cross-border teams, power imbalances can worsen if ratings and algorithm-based decision-making are unaccountable. The solution is not to ban these tools; it is to make them auditable and explainable, providing clear recourse for workers when mistakes happen.

There is also a broader change. As tasks move online, the demand for office space is shifting unevenly. In the U.S., office vacancies reached around 20% by late 2024, the highest level in decades, with distress in the sector nearing $52 billion. This does not mean cities will die; rather, it indicates a shift away from low-performing spaces toward digital infrastructure and talent. Employers will continue to focus on time zones, skills, and cost—rather than postal codes. Borderless AI labor will keep driving this change.

Rules for a fair marketplace in borderless AI labor

First, establish portable labor standards for digital work. Governments that buy AI services should require contractors—and their subcontracted platforms—to meet basic conditions, including living-wage floors based on purchasing power, mandated rest periods, and access to mental health support for high-risk jobs like content moderation. International cooperation can help align these standards with existing due diligence laws. A credible standard would connect buyers in cities like New York or Berlin to the outcomes for workers in places like Nairobi or Cebu.

Second, include algorithmic management in policy discussions. Regulators should require companies that use automated assignment, monitoring, or evaluation to disclose such practices, document their effects, and provide appeals processes. Evidence shows that companies already report governance measures, but their implementation often outpaces oversight. Clear rules, alongside audits by independent organizations, can reduce bias, limit intrusive monitoring, and protect the integrity of cross-border teams. Where national laws do not apply, public and institutional buyers can enforce contract obligations.

Third, invest in connectivity. An estimated 3 billion people still lack internet access. A rigorous estimate from 2023 places the global broadband investment needed for near-universal access at about $418 billion, mostly in emerging markets. This investment is essential infrastructure for borderless AI labor. Prioritize open-access fiber, shared 4G/5G in rural areas, and community networks. Public funds should promote open competition and fair-use rules so smaller firms and schools can benefit.

Fourth, speed up cross-border payments and credentials. Workers need quick and low-cost methods to get paid, demonstrate their skills, and maintain verified work histories. Trade organizations are already tracking a surge in digital services. The next step is mutual recognition of micro-credentials and compatible identity standards. Reliable certificates and verifiable portfolios allow employers to assess workers based on evidence, not stereotypes—an essential principle in borderless AI labor.

Preparing schools for borderless AI labor

Education systems must shift from a geography-focused model to a task-focused model. Start with language-aware and AI-aware curricula. Students should learn how to use model-assisted tools for translation, summarization, coding, and data cleaning. They also need to judge outputs, cite sources, and respect privacy. Employer surveys indicate substantial investment in AI skills and ongoing job redesign. Schools should reflect this reality with projects that involve actual work for external clients and peers in different time zones, building the trust that borderless AI labor values.

Next, teach platform literacy and how to promote portfolios. Many graduates will have careers that combine organizational roles with platform work. They must understand service-level agreements, dispute processes, rating systems, and the basics of tax compliance across borders. Capstone projects should culminate in public portfolios featuring versioned code, reproducible analyses, and evidence of collaboration across cultures and time zones. Credentialing should be modular and stackable, so a learner in Accra can combine a local certificate with a global micro-credential recognized by the same employer.

Finally, prioritize well-being and ethics. The data work behind AI can be demanding. Students who choose annotation, moderation, or risk analysis need training to handle exposure to harmful content and find pathways to safer, higher-value roles. Programs should normalize mental health support, rotate students out of traumatic tasks, and teach how to create safer processes—such as automated filtering, triage, and escalation—to reduce harm. The goal is not to deter students but to empower them and provide safeguards in a market that will continue to grow.

The world has already crossed a significant threshold. When digitally deliverable services surpass $4.5 trillion and developing economies exceed $1 trillion in exports, we aren’t discussing a future trend; we’re managing a current reality. Borderless AI labor is not just a concept; it involves a daily flow of tasks, talent, and trust—organized by algorithms, traded in global markets, and facilitated over networks. We can let this system develop by default, with weak protections, inadequate training, and increasing disparities. Or we can take action: establish portable standards for digital work, regulate algorithmic management, invest in connectivity, and teach for a task-driven environment. If we choose the latter, the potential is genuine. Millions who have been invisible to global employers can gain recognition, verifiable reputations, and access to safer, better-paying jobs. This is a policy decision—one that schools, ministries, and buyers can act on now, while the new market is still taking shape.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Amnesty International. (2025, April 3). Kenya: Meta can be sued in Kenya for role in Ethiopia conflict.

Brookings Institution. (2025, October 7). Reimagining the future of data and AI labor in the Global South.

Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT). (2024, January 30). Investigating content moderation systems in the Global South.

Deel. (2025, April 13). Global hiring trends show cross-border growth and 82% remote roles.

MSCI Real Assets. (2025, July 15). The office-market recovery is here, just not everywhere.

Moody’s CRE. (2025, January 3). Q4 2024 preliminary trend announcement: Office vacancy hits 20.4%.

OEC D. (2024, Mar.). Using AI in the workplace.

OECD. (2025, February 6). Algorithmic management in the workplace.

Oughton, E., Amaglobeli, D., & Moszoro, M. (2023). What would it cost to connect the unconnected? arXiv.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) via WAM. (2024, December 7). Developing economies surpass $1 trillion in digitally deliverable services; global total $4.5 trillion.

Upwork. (2023, December 12). Freelance Forward 2023.

World Economic Forum. (2025, January 7). Future of Jobs Report 2025 (press release and digest).

World Economic Forum. (2025, May 13). How AI is reshaping the future of informal work in the Global South.

World Trade Organization. (2025). Digitally Delivered Services Trade Dataset.