From Smartphone Bans to AI Policy in Schools: A Playbook for Safer, Smarter Classrooms

Published

Modified

Smartphone bans offer a blueprint for AI policy in schools Use age-tiered access, strict privacy, and teacher oversight Evaluate results publicly to protect attention, equity, and integrity

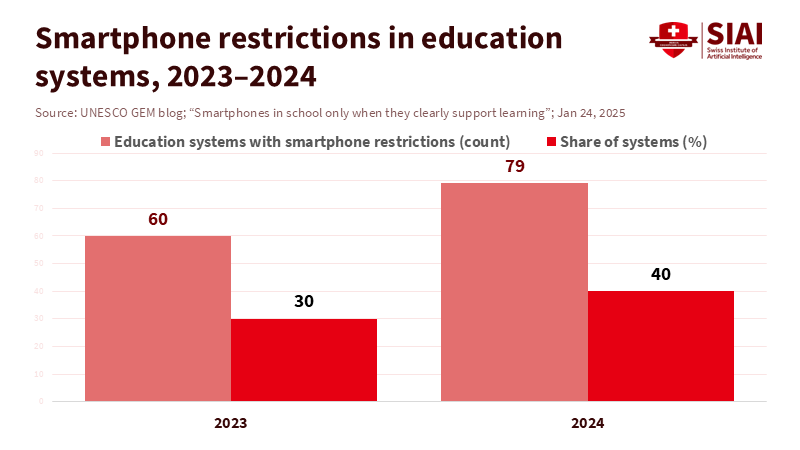

Let's begin with a significant figure: forty. By the close of 2024, a staggering 79 education systems, representing approximately 40% of the global education landscape, had enacted laws or policies curbing the use of smartphones in schools. This global trend is a clear indicator of how societies experiment with a technology, observe its impact, and then establish strict regulations for children. This pattern, which has been observed with smartphones, is now a pressing need for large language models. The parallels are undeniable. Both technologies are ubiquitous, designed to captivate users, and have the potential to divert students from learning at a pace that schools struggle to match. The question is not whether we need an AI policy in schools, but whether we can develop it with the same speed and clarity that the rise of smartphones has taught us to adopt.

What smartphone bans teach us about AI policy in schools

The success of smartphone bans over the past two years serves as a reassuring case study for policy. UNESCO tracked a swift shift from scattered rules to national prohibitions or restrictions. By the end of 2024, seventy-nine systems had implemented these policies, up from sixty the previous year. In England, national guidance released in February 2024 supports headteachers who ban the use of phones during the school day. The Netherlands implemented a classroom ban with limited exceptions for learning and accessibility, achieving high compliance quickly. Finland took action in 2025 to limit device use during school hours and empowered teachers to confiscate devices that were disruptive to the learning environment. These actions were not just symbolic; they established a straightforward norm: unless a device clearly supports learning or health, it should stay away.

The evidence on distraction backs this conclusion. In PISA 2022, about two-thirds of students across the OECD reported being distracted by their own devices or by others' devices during math lessons, and those who reported distractions scored lower. In U.S. classrooms, 72% of high school teachers view phone distraction as a significant issue. In comparison, 97% of 11- to 17-year-olds with smartphones admit to using them during school hours. One year after Australia's nationwide restrictions, a New South Wales survey of nearly 1,000 principals found that 87% noticed a decrease in distractions and 81% reported improved learning outcomes. None of these figures proves causation on its own. Still, combined, they indicate a clear signal: less phone access leads to calmer classrooms and more focused learning.

There is also a warning. Some systems chose a different approach. Estonia has invested in managed device use and AI literacy, rather than imposing bans, believing the goal is to improve teaching practices, not just to restrict tools. UNESCO warns that the evidence base still lags behind product cycles; solid causal studies are rare, and technology often evolves faster than evaluations can keep up. Good policy learns from this. It should set clear, simple boundaries while leaving space for controlled, educational use. That balance serves as a model for AI policy in schools, and this policy must be transparent, keeping all stakeholders informed and confident.

Designing AI policy in schools: age, access, and accountability

The second lesson is about design. The smartphone rules that worked were straightforward but not absolute. They allowed exceptions for teaching and for students with health or accessibility needs. AI policy in schools should follow this pattern, with a stronger focus on privacy. The risks associated with AI go beyond distraction. They also include data collection, artificial relationships, and mistakes that can impact grades and records. Adoption of AI is already widespread. In 2024, 70% of U.S. teens reported using generative AI, with approximately 40% using it for schoolwork. Teacher opinions are mixed: in a 2024 Pew survey, a quarter of U.S. K-12 teachers stated that AI tools do more harm than good, while about a third viewed the benefits and drawbacks as evenly balanced. These findings suggest the need for clear guidelines, not blanket bans.

A practical blueprint is straightforward. For students under 13, the use of school-managed tools that do not retain chat histories and block conversational 'companions' should be the norm. From ages 13 to 15, use should be permitted only through school accounts with audit logs, age verification, and content filters; open consumer bots should not be allowed on school networks. From the age of 16 onward, students can use approved tools for specific tasks, subject to teacher oversight and clear attribution rules. Assessment should align with this approach. In-class writing and essential tasks should be 'AI-off' by default unless the teacher specifies a limited use case and documents it. Homework can include 'AI-on' tasks, but these must be cited with prompts and outputs. The aim is not to trap students, but to maintain high integrity, steady attention, and visible learning.

Procurement makes the plan enforceable. Contracts should require vendors to turn off data retention by default for minors, conduct age checks that do not collect sensitive personal information, provide administrative controls that block "companion" chat modes and jailbreak plug-ins, and share basic model cards that explain data practices and safety testing procedures. Districts should prefer tools that generate teacher-readable logs across classes. These expectations align with UNESCO's global guidance for human-centered AI in education and with evolving national guidance that emphasizes the importance of teacher judgment over automation.

Evidence we have—and what we still need—on AI policy in schools

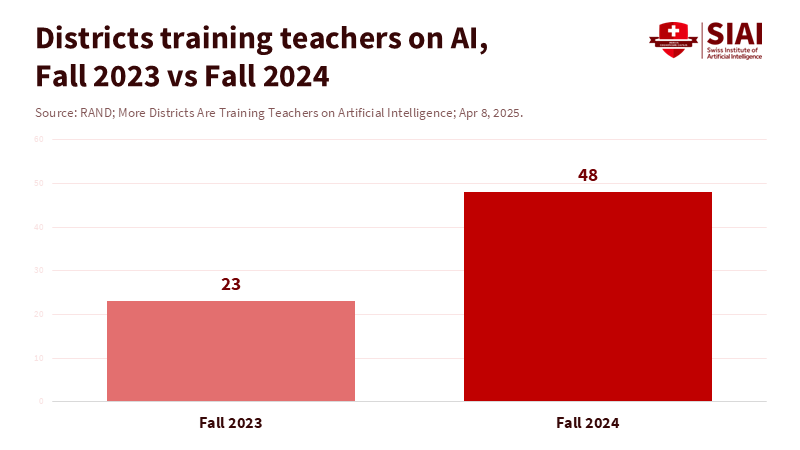

We should be honest about the evidence. For phones, the connection between distraction and lower performance is strong across systems; however, the link between bans and test scores remains under investigation. Some notable improvements, such as those in New South Wales, come from principal surveys rather than randomized trials. With AI, the knowledge gap is wider. Early data indicate increased usage by teachers and students, along with a rapid expansion of training. In fall 2024, the percentage of U.S. districts reporting teacher training on AI rose to 48%, up from 23% the previous year. At the same time, teen use is spreading beyond homework. In 2025 research, 72% of teens reported using AI "companions," and over half used them at least a few times a month. This trend introduces a new risk for schools: AI tools that mimic friendships or therapy. AI policy in schools should draw a clear line here, and ongoing evaluation is crucial for its success.

Method notes are essential. PISA 2022 surveyed roughly 690,000 15-year-olds across 81 systems; the 59–65% distraction figures represent OECD averages, not universal classroom rates. The Common Sense figures are U.S. surveys with national samples collected in 2024, with follow-ups in 2025 on AI trust and companion use. RAND statistics come from weighted panels of U.S. districts. The U.K. AI documents provide policy guidance, not evaluations, and the Dutch and Finnish measures are national rules that are just a year or so into implementation. This evidence should be interpreted carefully; it is valuable and credible, but still in the process of development.

This leads to a practical rule: every district AI deployment should include an evaluation plan. Set clear outcomes in advance. Monitor workload relief for teachers, changes in plagiarism referrals, and progress for low-income students or those with disabilities. Share the results on a public schedule, using clear and concise language. Smartphones taught us that policies work best when the public sees consistent, local evidence of their benefits. AI policy in schools will gain trust in the same way. If a tool saves teachers an hour a week without increasing integrity incidents, keep it. If it distracts students or floods classrooms with off-task prompts, deactivate it and provide an explanation for why.

A principled path forward for AI policy in schools

What does a principle-based AI policy in schools look like in practice? Start with transparency. Every school should publish a brief AI use statement for staff, students, and parents. This statement should list approved tools, clarify what data they collect and keep, and identify who is responsible. Move to accountability. Schools should maintain audit logs for AI accounts and conduct regular spot checks to ensure the integrity of assessments. Include human oversight in the design. Teachers should decide when AI is used and remain accountable for feedback and grading. Promote equity by design. Provide alternatives for students with limited access at home. Ensure tools are compatible with assistive technology. Teach AI literacy as part of media literacy, so that students can critically evaluate AI-generated outputs, rather than simply consuming them.

The policy should extend beyond the classroom. Procurement should establish privacy and safety standards in line with child-rights laws. England's official guidance clarifies what teachers can do and where professional judgment is necessary. UNESCO promotes human-centered AI, emphasizing the importance of strong data protection, capacity building, and transparent governance. Schools should choose tools that turn off data retention for minors, offer meaningful age verification, and enable administrators to block romantic or therapeutic "companion" modes, which many teens now report trying. This last restriction should be non-negotiable for primary and lower-secondary settings. The lesson from phones is clear: if a feature is designed to capture attention or influence emotions, it should not be present during the school day unless a teacher explicitly approves it for a limited purpose.

The number that opened this piece—40% of systems restricting phones—reflects a social choice. We experimented with a tool in schools and found that without a clear set of rules, it disrupted the day. This lesson is relevant now. Generative AI is emerging faster than smartphones did and will infiltrate every subject and routine. A confusing message will result in inconsistent rules and new inequalities. A simple, firm AI policy in schools can counteract this. It can safeguard attention, minimize integrity risks, and still enable students to learn how to use AI effectively. The path is clear: establish strict rules for age and access, ensure strong logs, prioritize transparent procurement, and include built-in evaluations. If policymakers adopt this plan now, the following statistic we discuss won't be about bans. It will reflect how many more hours of genuine learning we can achieve—quietly, week after week, in classrooms that feel focused again.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Australian Government Department of Education – Ministers. (2025, February 15). School behaviour improving after mobile phone ban and vaping reforms.

Common Sense Media. (2024, September 17). The Dawn of the AI Era: Teens, Parents, and the Adoption of Generative AI at Home and School.

Common Sense Media. (2025, February 6). Common Sense makes the case for phone-free classrooms.

Department for Education (England). (2024, February 19). Mobile phones in schools: Guidance.

Department for Education (England). (2024, August 28). Generative AI in education: User research and technical report.

Department for Education (England). (2025, August 12). Generative artificial intelligence (AI) in education.

Eurydice. (2025, June 26). Netherlands: A ban on mobile phones in the classroom.

Guardian. (2025, April 30). Finland restricts use of mobile phones during school day.

Guardian. (2025, May 26). Estonia eschews phone bans in schools and takes leap into AI.

OECD. (2024). Students, digital devices and success.

OECD. (2025). Managing screen time: How to protect and equip students to navigate digital environments?

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education.

RAND Corporation. (2025, April 8). More Districts Are Training Teachers on Artificial Intelligence.

UNESCO. (2023/2025). Guidance for generative AI in education and research.

UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report team. (2023; updated 2025, January 24). To ban or not to ban? Smartphones in school only when they clearly support learning.