Deepfake Law and Campus Justice: When Evidence Fails, Duty Begins

Input

Modified

Deepfakes are breaking trust in evidence Campuses need rapid takedowns, provenance checks, and victim support Lawmakers must close gaps now with clear liability and cross-border enforcement

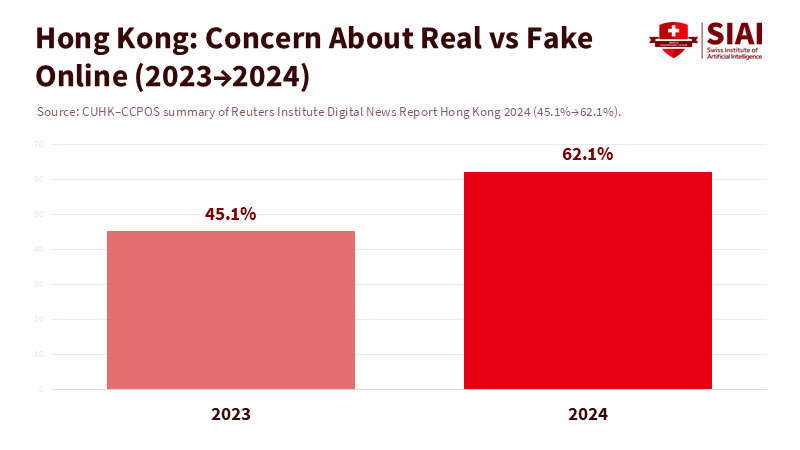

We used to view images as facts. In Hong Kong, that belief changed when a law student faced accusations of creating over 700 indecent deepfake images of classmates and teachers. The university first sent a warning letter, and then the privacy watchdog launched a criminal investigation. The shock came not only from the act itself but also from the delay between the harm and the response. That harm is real. A fake image can appear in search results, lead to harassment, and last long after its creator is gone. In 2024, the number of Hongkongers who worried about what is real or fake online jumped by 17 percentage points within a year. Trust eroded quickly. Policy needs to keep up. “Calamus gladio fortior”—the pen is mightier than the sword—reflects an even older Greek saying: η γλώσσα κόκκαλα δεν έχει και κόκκαλα τσακίζει. Words, and now synthetic images, can cause harm without physical contact. This is why deepfake law must stop reacting to the last crisis and start protecting future victims.

The case for deepfake law now

The moral issue is clear: non-consensual sexual deepfakes are abuse. The legal aspect is more complicated. Many legal systems still rely on the concept of a "real" image, a public disclosure, or a measurable financial loss. Harm without distribution often gets ignored. The Hong Kong case highlighted this gap: policy changes occurred after the outrage, rather than being proactive. The university's first action—a warning letter—seemed minor compared to the extent of the harm. Authorities only initiated a probe later. This pattern isn't unique to Hong Kong. Throughout East Asia, laws and institutional policies struggle to keep pace with the speed and scope of synthetic abuse.

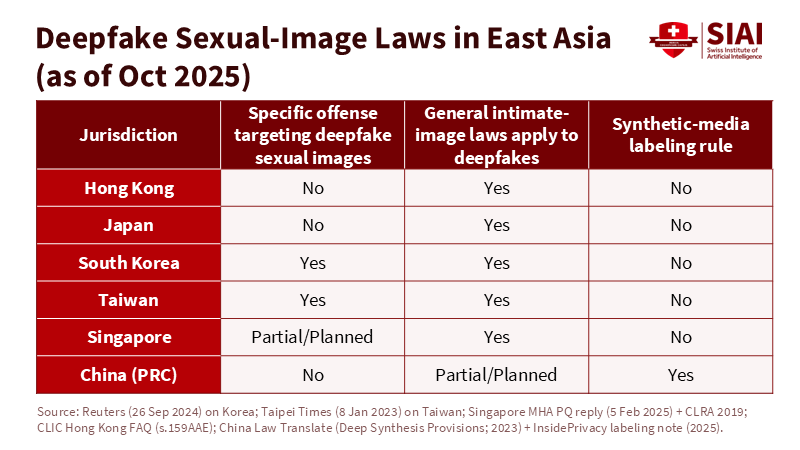

What should deepfake law mean in practice? South Korea now makes it illegal to produce, distribute, watch, or possess sexually explicit deepfakes, with penalties of up to three years and harsher sentences for creating or sharing content. Taiwan updated its Criminal Code in 2023 to address deepfake sexual imagery and strengthened takedown responsibilities for intimate images. China regulates deep synthesis providers and, starting in 2025, introduced new labeling rules for AI-generated content. The region presents three approaches: criminalizing actions by producers and viewers, establishing consent-based protections for intimate images along with takedown duties, and implementing platform-centric labeling. None of these alone is sufficient on a campus. Victims need swift action, not just legislation.

This patchwork system is particularly relevant for universities that have students from diverse countries, utilize cloud storage, and rely on platforms based outside their own institutions. Hong Kong adheres to general laws governing offenses and data privacy. Japan typically uses defamation or business obstruction laws to target those who spread content, leaving non-distribution harms in uncertain areas. Singapore is working to clarify that sexually explicit deepfakes fall under existing laws and has already tightened rules during election periods and for online harms. The landscape is inconsistent, and students suffer as a result.

Deepfake law on campus

Universities are not courts, but they often act as first responders. The Hong Kong case illustrates what happens when university policy and practice don't align. Ensuring student safety requires prompt, rights-respecting actions, even as external investigations are underway. A deepfake law perspective identifies three key responsibilities: first, immediate containment, which includes rapid hashing, removal of search results, and takedown requests to service providers. Second, trauma-informed support provides counseling, academic adjustments, and a safe classroom environment. Third, evidence preservation with privacy: logs, hashes, and secure statements that do not force victims to relive their trauma. HKU has focused on well-being and academic adjustments; this principle should be standard practice, not an exception.

Campus policy must also address the source of the problem. Most non-consensual deepfakes target women and girls. Data from South Korea indicate a sharp increase in offenses committed by youth, with cases numbering in the hundreds per year since 2021. Platforms hosting deepfake pornography are fragile yet resilient; one primary site shut down in 2025 after losing a critical service provider, but mirrors appeared quickly. Universities cannot police the entire internet, but they can prepare by establishing standard operating procedures, designating dedicated contacts for takedowns, and pre-signing agreements with major platforms. This planning reduces the first 48 hours—the timeframe when search results solidify and harassment peaks.

The trust issue extends beyond sexual abuse. Students tell us they have doubts about what they see. In Hong Kong, concern over online authenticity grew from 45.1% to 62.1% between 2023 and 2024. This widespread fear influences how allegations are perceived, how rumors spread, and how authorities respond to them. Provenance tools can help. The C2PA "Content Credentials" standard, supported by Adobe, Microsoft, and camera manufacturers such as Leica and Sony, enables the attachment of tamper-evident data to photos and videos. Yet, adoption varies across devices and platforms, meaning campuses must implement provenance for official media while also responding aggressively when abusive content lacks credentials.

From legal gap to institutional duty: an implementation blueprint for deepfake law

Here is the straightforward test for deepfake law in education: can a victim receive help before reputational damage becomes permanent? Start with a campus "48-hour rule." Within two days of a report, a university should (1) confirm receipt and safety measures, (2) issue preservation notices, (3) submit standardized takedown requests, (4) offer academic adjustments and counseling, and (5) provide a written rights sheet detailing police reporting, privacy, and appeal options. This isn't overreaching; it is a way to reduce harm. South Korea's stricter laws represent a step in the right direction. Taiwan's 2023 reforms and takedown responsibilities lay the groundwork for action. China's labeling regime emphasizes the importance of provenance, even if it does not prioritize victims. Together, they highlight what universities can implement now without waiting for perfect national legislation.

Concern in Hong Kong increased by 17 points in a single year. This sentiment justifies bold actions: university-wide provenance for official media, a public "report deepfakes" channel, and agreements with platforms for timely takedowns. The more students distrust images, the more they need clear protocols in place. Clearer protocols will reduce the chances of rumors replacing proof. This isn't only a task for student affairs; it's an institutional risk management issue.

Next, deepfake law should be incorporated into the codes of conduct. Define non-consensual synthetic sexual imagery as a specific violation, with stricter penalties for repeat offenders, coercion, or widespread distribution. Explicit offenses should include doxxing, extortion, and unauthorized "nudification" app use. Create pathways for amnesty for bystanders who report quickly. On the prevention front, include awareness training in the orientation process. Students should learn three key points: how to verify provenance, how to file a report, and how to support peers without sharing content. This isn't about regulating speech; it is about ensuring safety. The goal is to minimize the time between harm and help.

Finally, link campus actions to law reform. Universities can provide lawmakers with insights they often lack: real timelines, points of failure, and cross-border challenges. The quickest improvements tend to be procedural—clearer takedown obligations, safe-harbor rules for good-faith reporting, and standardized evidence formats that spare victims from repeated interviews. Legislatures can then draft laws that assume the existence of synthetic content rather than relying solely on reality and increase penalties based on reach and intent. This approach enables us to transition from reactive measures to proactive ones.

Anticipating the hard questions

Does criminalization risk overreach? It can. However, evidence shows that deepfake laws work best when explicitly focused on non-consensual sexual content, threats, and fraud, along with due-process protections. South Korea's reforms target production, distribution, and consumption; Taiwan couples offenses with takedown requirements; and Singapore is clarifying coverage while enacting strict laws for election periods and online harms. This model—combining scope clarity with procedural efficiency—respectfully balances free speech with the protection of victims.

What about labeling and provenance standards—can they solve the problem? Not by themselves. C2PA "Content Credentials" can provide a trackable history from capture to publication across supported cameras and software, and adoption is growing. However, gaps in coverage remain among phones and major platforms, limiting their deterrent effect. The solution requires a layered approach: implementing provenance by default for official campus media, educating students on how to verify credentials, and providing legal support when labels are absent or removed. This narrows, but does not entirely close, the trust gap.

Will stricter laws push abuse underground? Some is already happening. Yet, laws still matter because they influence the behavior of hosts, search engines, and payment intermediaries. The shutdown of a prominent deepfake porn site following a critical provider's exit shows how pressure on infrastructure can decrease supply. Universities can enhance this effect by sending standardized notices and preserving hashes for law enforcement. At the same time, campus policies should avoid requiring victims to prove the "viral reach" of their content before assistance is provided. Help should rely on the absence of consent, not the content's popularity.

Is education doing enough? Not yet. Students need clear, repeated messages: non-consensual synthetic sexual imagery constitutes violence; reporting helps; sharing spreads harm and can be illegal. Campus adults—faculty, counselors, and residence staff—need training to respond effectively without moral judgments. The tone must be clinical and compassionate. A victim is not a case study; a rumor is not an investigation. Responses must match the scale of the damage, which, in the age of search engines, can multiply quickly.

What does duty look like tomorrow?

We should abandon the myth that a perfect courtroom standard will solve the daily challenges on campus. Deepfake law must start where students live and learn. This requires three immediate actions. First, prioritize speed: enforce the 48-hour rule for containment, support, and evidence preservation. Second, ensure clarity: establish a clear conduct offense for synthetic sexual abuse, supported by survivor-focused processes and appeal rights for the accused. Third, implement provenance by default: utilize Content Credentials for official media, provide verification training, and form partnerships with platforms that support C2PA signals. Combine these actions with ongoing legal reforms in South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and China, adjusting them to local standards and rights.

We conclude as we began. In the past, an image was often used to represent a fact. Today, an image can serve as a weapon. "Calamus gladio fortior" sounded poetic when the battle was between print and steel. Nowadays, it is literal. A fake image can cause more harm than a blade, as it can repeatedly inflict its damage. The Hong Kong case stands as a warning. The rise in public concern is a call to action. Universities and lawmakers should view non-consensual synthetic sexual imagery as an attack on individuals and their reputations. The solutions are clear: swift takedowns, survivor-first protocols, precise violations, and tracks of provenance that follow the file. If we act, the evidence can regain its significance. If we delay, rumors will dictate the truth. Deepfake law should restore the balance in favor of reality.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Adobe. (2024). Seizing the moment: Content Credentials in 2024. https://blog.adobe.com.

C2PA. (n.d.). Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity.

China Law Translate. (2022). Provisions on the Administration of Deep Synthesis Internet Information Services. https://chinalawtranslate.com.

CGTN. (2025, Sept. 1). China enforces new rules on labeling AI-generated content. https://news.cgtn.com.

HKU. (2025, July 12). HKU responds to media enquiries on individual student allegedly using AI tools to create indecent images.

HKU. (2025, July 17). Statement by HKU on individual student allegedly using AI tools to create indecent images.

Reuters Institute—CUHK. (2024). Digital News Report Hong Kong 2024 summary. https://ccpos.com.cuhk.edu.hk.

Reuters. (2024, Sept. 26). South Korea to criminalise watching or possessing sexually explicit deepfakes. https://reuters.com.

Straits Times. (2025, July 15). Hong Kong opens probe into AI-generated porn scandal at university. https://straitstimes.com.

Taipei Times. (2023, Jan. 8). Bill to curb deepfake pornography clears legislature. https://taipeitimes.com.

Taipei Times. (2023, Aug. 15). New intimate image rules take effect. https://taipeitimes.com.

The Verge. (2024, Aug. 21). This system can sort real pictures from AI fakes—why isn’t it used widely? https://theverge.com.

Yahoo/CBS News. (2025, July 15). AI-generated porn scandal rocks oldest university in Hong Kong.