Education and Dollar Dominance: What a Weaker USD Means for Universities and Students

Input

Modified

The dollar’s slide plus tariffs eroded its safe-haven aura Campuses face pricier labs and shakier international demand Fix it with rule-based visas, FX-hedged tuition, and research tariff carve-outs

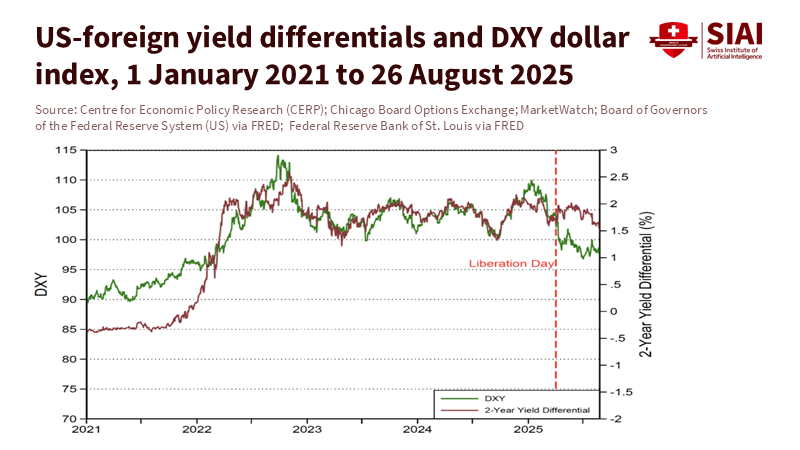

The most telling number this year is not a test score or tuition amount. It is the exchange rate. In April 2025, the dollar dropped to its lowest level against the Swiss franc since 2015. By early September, it had marked its worst January-to-June stretch during the modern era of floating rates. This decline was not temporary; it showed a loss of faith in U.S. assets and in policies that made trade more expensive and planning more difficult. For higher education—our country’s top services export—this change is very real. It affects the price foreign families pay to study, the costs labs incur to import equipment, and the returns endowments see on global investments. A weaker dollar can make learning in the U.S. appear more affordable to people overseas. However, tariffs and uncertainty can erode those benefits more quickly than the admissions cycle, posing significant challenges to the affordability of U.S. education.

Why Education and Dollar Dominance Matter Now

Education and dollar dominance intersect every day in campus financial records. International students contributed $43.8 billion to the U.S. economy in the 2023–24 fiscal year and supported approximately 378,000 jobs. The United States also welcomed a record 1,126,690 international students in the 2023–24 academic year. These numbers show how teaching and research serve as exports priced in dollars and paid from abroad. When the dollar weakens, the effective sticker price drops for families paying in rupees, euros, or yen. When policy risks increase, some of those families hesitate, and governments may discourage studying abroad. In 2025, China issued new warnings about traveling and learning in the U.S., reminding us that services trade is strategic, not automatic. Education and dollar dominance rise and fall together with trust in U.S. policy, since trust determines the premium global students and sponsors are willing to pay for a U.S. degree.

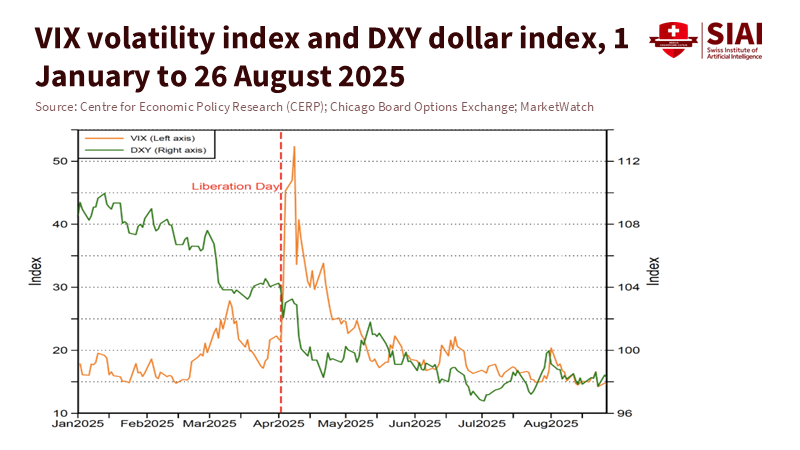

A weaker dollar did not appear out of nowhere. It arrived amid new or threatened tariffs across many areas of trade. Markets took notice. In April, as tariff discussions intensified, the dollar dropped sharply, even reaching a decade-low against the franc. By late summer, analysts were still questioning whether the currency’s safe-haven reputation had weakened. Oil markets also cooled, with Brent prices hovering around $70 and official forecasts predicting lower averages. This combination of tariffs, currency, and lower energy costs directly influences campus decisions: airfare for students, electricity expenses for facilities, and bids for microscopes. Administrators focusing solely on domestic inflation miss the larger picture. Suppose education and dollar dominance are our perspectives. In that case, we need to watch exchange rates, energy prices, and border taxes together, as they collectively determine the affordability of an American education for the world.

How Tariffs Reshape Education and Dollar Dominance

Tariffs do not stay at the port; they extend to lab benches. Studies of the 2018–19 trade war found that U.S. import prices absorbed most tariff increases, with pass-through rates near 90–100% at the border. This trend matters now because research campuses import many instruments classified under HS Chapter 90. For example, consider a $200,000 mass spectrometer from Europe or Japan. If a new 10–15% duty applies and the pass-through is nearly complete, the delivered price rises by about $20,000–$30,000 before service contracts. The BLS producer-price index for laboratory analytical instruments stood at about 192 in August 2025, and equipment wholesalers’ margins have been unstable this year. Tariffs add to that base. For a grants office, this means fewer funded awards within a given budget. For a dean, it may mean delaying a faculty hire to cover instrument expenses. For students, this could mean that lab fees will increase in the next term. The chain is straightforward, but the totals add up.

Policy is still changing. In late September, the administration introduced new duties on lumber and furniture, just days after imposing steep tariffs on branded drugs and heavy trucks. Earlier in the summer, it proposed 15–20% “world tariffs” for partners without specific deals. Even when exemptions arise, uncertainty remains the norm. For education and dollar dominance, the message is clear. When tariffs expand and rules fluctuate, global families and sponsors hold back, and universities’ research costs rise. A decline in currency value can make tuition more affordable for some groups. Still, the credibility loss caused by unpredictable trade policies directly impacts the dollar story that investors share: the safe-haven premium decreases when rules appear inconsistent. This situation results in slower application growth, more expensive laboratory tests, and budgets that are more difficult to manage.

Energy offers some relief. Oil prices have dropped to the high $60s due to rising supply and weak demand, and the EIA predicts an average Brent price of under $70 for 2025, with further declines expected in 2026. For a medium-sized residential campus spending around $12 million on utilities, a 10–15% reduction in fuel-related costs could free up $1–$2 million. Note: this rough estimate applies historical pass-through rates from crude oil to delivered electricity and heat (which differ by region) and assumes a one-year lag. These savings are significant, but they are smaller than the impact of a 10% tariff shock on a $50 million research procurement plan. They do not help students dealing with visa delays or sponsors navigating geopolitical tensions. Cheap oil cannot restore trust. Only consistent policies can achieve that.

Policy Actions to Align Education and Dollar Dominance

Universities should view exchange risk as a student-access issue, not just a treasury matter. If education and dollar dominance are the framework, bursars and admissions should include currency clauses that allow families to lock in tuition at home-currency prices upon acceptance, centrally hedged by the institution. Note: A rolling 12- to 24-month hedge using forwards sized to expected cash flows can limit downside risk for both parties without speculative risks. The same approach applies to endowed scholarships in foreign currencies. A weaker dollar increases the translated value of foreign equity holdings, and the endowment returns for FY 2024 were strong. However, the 10-year average is about 6.8%, and volatility has returned. Board members should now link FX and tariff scenarios to spending policies, ensuring that aid commitments remain stable in the event of market fluctuations.

Immigration policy is the quickest lever. The Open Doors data indicate steady demand for more than 1.1 million international students, with record graduate enrollment and participation in OPT. Keep that door open and consistent. If tariffs increase research costs, the best long-term solution lies in attracting talent that boosts productivity. Commerce already counts education-related travel as an export; it should be treated as a strategic export. This requires consistent visa timelines, improved visa interview capacity, and automatic STEM OPT extensions that align with peer economies. It also necessitates clear communication during periods of rising geopolitical tension—do not allow foreign travel warnings to shape the narrative for families abroad. The key defense for education and dollar dominance is a stable, rules-based environment.

Research procurement needs protection from tariffs. Congress and relevant agencies can exempt crucial scientific instruments and inputs from broad tariffs when no domestic substitutes exist at scale, with periodic reviews. This is not a loophole; it is an investment rule. Previous evidence suggests that tariffs increase domestic prices, even when import shares are reduced. Passing costs onto labs hampers the very innovation engine that drives long-term competitiveness. A transparent waiver process, tied to cataloged HS codes and limited in time, would keep projects on track without dismantling enforcement. Meanwhile, federal sponsors should tie grant ceilings to relevant producer price indexes to ensure awards maintain real value for laboratory equipment.

A Practical Conclusion for Education and Dollar Dominance

Universities should budget considering the drop in oil prices, but avoid overreliance on it. With Brent near $70, campuses can use lower energy expenses to provide need-based aid and international emergency grants. Connect that support to FX-adjusted criteria: a student from a country with a sharply depreciated currency might suddenly face a funding gap despite an overall weaker dollar. Financial aid offices can incorporate simple FX stress tests into annual renewal reviews and adjust support within policy constraints. This is not charity; it is a retention strategy in a world where currencies fluctuate quickly than academic terms.

Lastly, let’s be clear about comparative advantage. The United States has unmatched strength in finance, research, higher education, and advanced services. This “exorbitant privilege” has never relied solely on manufacturing; it has been built on trust in institutions that value global assets and develop international talent. Analysts still believe the dollar’s reserve role is secure for years to come, but 2025 demonstrated that markets will question that belief when policies create uncertainty. For education and dollar dominance, the takeaway is simple: do not undermine the sector that positions the U.S. as the world’s classroom, attracting students, sponsors, and scholars who sustain the currency’s network effects. Protect the rules, not just the headlines.

We should anticipate objections. Some will claim a weaker dollar is a clear advantage for attracting international students, or that tariffs protect emerging domestic suppliers of scientific instruments. The first argument overlooks the chilling impact of policy unpredictability on long-term family decisions and the risk of retaliatory travel advisories. The second overestimates the short-term capacity of specialized capital goods. Research indicates that tariff costs are primarily borne by U.S. buyers and are subsequently passed through to supply chains. To boost domestic capabilities, we should combine targeted production incentives with reliable procurement and standards, rather than imposing blanket duties that inflate research costs across the board. Education and dollar dominance require policies that reduce friction, not increase it.

A final call to action. Reflect on the statistic that started this piece: a currency decline sufficient to undermine the dollar’s safe-haven image amid widespread tariffs. This combination could influence campus finances for a decade if we allow it to. The solution is not abstract. Ensure visa processes are fast and reliable. Create tuition and scholarship hedges that address families’ realities. Protect research inputs from excessive tariffs and link grant ceilings to instrument prices. Use today’s energy savings to support need-based aid. Most importantly, act and legislate as a rules-based economy. Suppose we synchronize education and dollar dominance with clear, open, and stable policies. In that case, the world will continue to invest in U.S. classrooms and the dollar that funds them.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2019). The Impact of the 2018 Tariffs on Prices and Welfare (NBER Working Paper No. 25672). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2020). Who’s Paying for the U.S. Tariffs? A Longer-Term Perspective. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 110, 541–546.

Al Jazeera. (2025, July 30). ‘Exorbitant privilege’: Can the U.S. dollar maintain its global dominance?

Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). (2025, Feb. 5). U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services—Annual 2024 (services exports and education-related travel).

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (2025, Sept. 10). Producer Price Indexes—August 2025; FRED series WPU118603 (Laboratory Analytical Instruments).

Energy Information Administration (EIA). (2025, July 8). Press release: EIA revises crude oil price forecast; expects Brent to average < $70 in 2025 and ~$58 in 2026.

Institute of International Education (IIE). (2024, Nov. 18). Open Doors 2024 Press Release (1,126,690 international students; record graduate/OPT).

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2025, Aug. 13). Oil Market Report—August 2025 (Brent near $70/bbl; low volatility).

NAFSA. (2024, Nov. 18). International students contribute $43.8 billion and support 378,175 jobs; Economic Value Tool.

NACUBO–Commonfund. (2025, Feb. 12). U.S. Higher Education Endowments: 11.2% FY 2024 return; 10-year average 6.8%.

Reuters. (2025, Apr. 11). Dollar slides to decade-low vs Swiss franc as U.S. assets sell off.

Reuters. (2025, Sept. 8). Dollar’s haven status may have always been a mirage (weak H1 performance).

Reuters. (2025, Sept. 26). Trump imposes steep tariffs on drugs and heavy trucks.

Reuters. (2025, Sept. 30). Trump sets 10% tariff on lumber imports, 25% on cabinets and furniture.

Reuters. (2025, July 28). Trump eyes “world tariff” of 15–20% for most countries.

U.S. Department of Commerce / International Trade Administration. (2025). Education-related travel exports (BEA)—value and rank in 2024.

Wall Street Journal (live coverage). (2025, Apr. 9). China warns citizens about travel and study in the U.S.