End the Parenting Arms Race: Low Fertility Education Policy

Input

Modified

Fertility is falling because systems and costs—not desire—make second births hard Peer competition magnifies housing, childcare, and career penalties into a one-child arms race Cap childcare, decouple school access, expand father leave

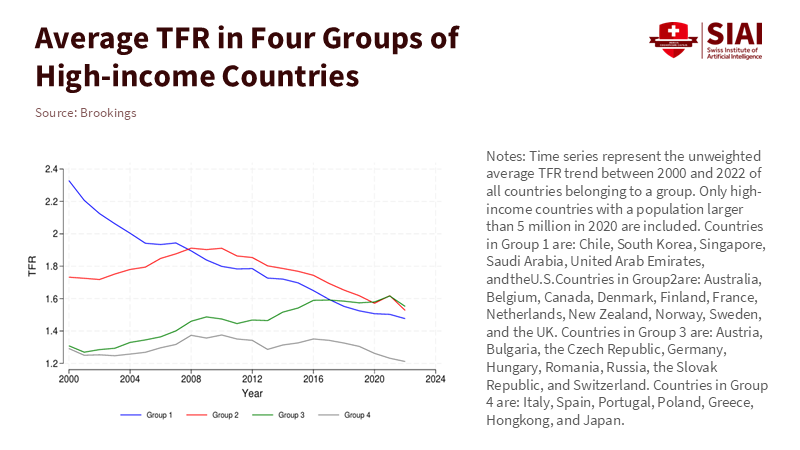

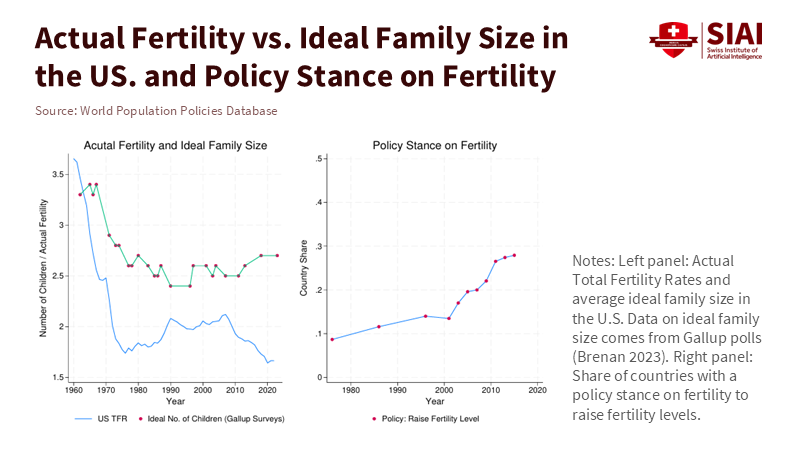

In 2023, Europe's total fertility rate fell to a historic low of 1.38. Not long ago, this number would have been unimaginable outside a war or depression. In South Korea, the lifetime birth rate per woman dropped to 0.72 in 2023, rising only to 0.75 in 2024. This still marks the lowest fertility rate in the world, even with a rise in marriages and various family incentives. Surveys show that while the desire to have children remains, the timing of starting a family and the decision to have a second child have shifted. The gap between desired and actual births is the policy challenge. The gap between desired and actual births is a policy challenge—one that a low fertility education policy must directly address. This gap encompasses housing affordability, childcare costs, labor market penalties for mothers, and an education system that converts peer pressure into a competition over status. The uncomfortable reality is that parental peer pressure is not confined to East Asia; it is a global phenomenon that modern digital tools and school networks can either escalate into a race or channel into a collaborative investment in learning. Our goal is to reshape the system so that comparisons no longer punish families for their size.

The Peer-Pressure Hypothesis Needs a Better Model

The standard narrative is that as parents connect through neighborhood WhatsApp groups, school portals, and social media, they compare everything—kindergarten phonics to high school exam rankings. Greater connectivity leads to more comparisons. These comparisons result in higher spending per child, which in turn leads to lower fertility rates. While this idea holds some truth, it is not complete. Peer pressure acts as a channel; it depends on factors that turn anxiety into action. Three main factors shape this pressure across cultures. First, living near "good schools" enforces zero-sum competition within neighborhoods. Rising price-to-income ratios have pushed many prospective parents out of safe areas for raising children. Second, net childcare costs can significantly reduce take-home pay, making deciding to have a second child feel daunting. Third, work-related penalties—wider in some regions but present nearly everywhere—turn the intensity of parenting into a burden on mothers. Together, these issues turn regular social comparisons into a costly race.

A better understanding must also include timing. Critics argue that academic competition intensifies between the ages of 10 and 15. At the same time, many couples consider having a second child between the ages of 24 and 34. However, families don't wait until middle school to form their expectations. They factor in what they believe is necessary to maintain their standing, influenced early on by the norms of their networks regarding preschool tutoring, daycare costs, and the challenges faced after maternity leave. Evidence from the OECD and national statistics indicates that factors influencing fertility—such as housing affordability, access to early childhood education and care (ECEC), and the design of parental leave—begin to impact decisions well before adolescence. When these constraints become more severe, birth rates decline even when the desired family size remains constant. This underscores that the critical issue is viability, not desire.

Low Fertility Education Policy: What the Data Say (2023–2025)

The trend across advanced economies is clear. The EU's fertility rate fell to 1.38 in 2023, with births declining by 5.4% in a single year, marking the most significant annual drop since 1961. This is not just a minor fluctuation; it signals a structural issue. During the same period, OECD data show that the average fertility rate remains around 1.5, with a long-term downward trend since the 1960s, resulting from similar factors: later partnerships, high housing costs, unstable early-career jobs, and the costs and organization of childcare and parental leave. Notably, Nordic countries, often cited as examples where culture outweighs policy—thanks to generous benefits—are also seeing declines. Norway's rate fell to about 1.40 in 2023, despite exceptional parental leave and subsidized childcare. This illustrates that heightened expectations for good parenting can overwhelm even the best programs. This is why we need to address the factors that escalate competition—particularly in education and housing—rather than simply extending cash benefits.

South Korea, a leader in "intensive parenting," offers a cautionary example. After hitting a record low of 0.72 in 2023, the total fertility rate rose slightly to 0.75 in 2024, supported by a resurgence in marriages and improved work-family policies. However, the system still directs parental anxiety toward private spending. A government survey revealed that nearly half of children under six are enrolled in cram schools (hagwon), with official statistics estimating private education costs at approximately $19.5–$21 billion USD for the 2023–2024 period, despite a shrinking student population. Governments have tried implementing curfews for cram schools and modifying entrance exams. Still, analysts repeatedly emphasize that unless pressure is alleviated within mainstream education. The job market becomes less winner-take-all, and families will continue to manage risk by having one child at a time. The policy solution is not to drive tutoring underground but to neutralize it by enhancing public schools and making supplemental learning accessible to everyone.

The psychological effects are not exclusive to Korea or China. Recent studies in Europe and North America show the rise of "intensive parenting" norms and how social comparisons, primarily through parent-focused social media, increase anxiety without necessarily enhancing education. OECD's PISA 2022 reports highlight pressures related to well-being that align with parental fears. Public health data and national surveys now indicate how adult social media use increases parental anxiety about children's futures. This shows that the peer-pressure mechanism is widespread; the "arms race" emerges when schools and platforms establish leaderboards, housing markets impose costs based on proximity to those leaderboards, and childcare systems make having a second child seem like doubling the investment. This dynamic exists in London, Los Angeles, and Seoul alike.

What would it look like to shift this system from competition to cooperation? Start with understanding the feasibility constraints. In places where ECEC availability is high and net childcare costs are kept low, parents are less likely to delay having a second child. Research from Europe and the Nordic countries indicates that improving access to childcare increases first-birth rates and, in some cases, boosts overall fertility. Similarly, longer, well-compensated father-specific leave that genuinely encourages behavior changes—not just for show—reduces penalties for mothers and stabilizes family planning. None of these levers will eliminate comparison; they will adjust the costs of competing while significantly enhancing collaboration. If a community's default is that every four-year-old can access a rich, engaging preschool experience; if every over-subscribed school provides controlled choices without housing market pressures; if every family can access tutoring through schools without shame or fees—then parents will no longer feel that having another child means falling behind.

Building a Low Fertility Education Policy That Lowers Costs and Pressure

The first step is to provide universal, high-quality early childhood education and care starting at 18 months, with prices capped on a progressive scale. This should ensure net childcare costs remain minimal for median-income families. Merely expanding available spots isn't enough; costs need to be predictable when deciding to have a first or second child. Countries that set clear fee caps and guarantee spots will reduce the variation that leads to risk-averse behavior. Aiming for the best-performing cost burdens in the OECD—close to 5% of disposable income where budgets allow—alongside quality standards for staffing, curriculum, and hours aligned with the workday, will significantly enhance feasibility. Such changes, rather than annual subsidies eroded by waiting lists, will make a real difference.

The second step is to disconnect access to schools from housing wealth during early education. When a few sought-after schools offer an admissions advantage, families compete for properties in those areas, further raising prices. This situation penalizes larger families twice—once through higher mortgage costs and again through the time burden. Education ministries and local governments can alleviate this pressure by expanding school catchments, increasing capacity in popular schools, utilizing controlled choice or lotteries in high-demand scenarios, and publishing quality metrics that focus on value-added and well-being, rather than just raw test scores. Concurrently, housing ministries should pilot affordability measures in densely populated family areas—such as shared equity or long-term rental options—to maintain neighborhoods that are friendly to families and accessible to middle-income parents. This approach involves educating policy through various means, but it can effectively influence fertility. When parents believe they can secure a good education without competing in a bidding war, they will be less likely to limit the size of their families.

The third step is to make supplemental learning a public resource rather than a private competition. Many systems initially started offering school-based tutoring after the pandemic, but later let it fade away. This should be reinstated as a permanent program: high-quality, curriculum-aligned sessions available before, during, or after school, free of charge, and targeting families less likely to participate. In areas with a strong private tutoring culture, governments can ensure transparency and quality, while also funding school-based options to reduce stigma and cost. The aim should not be to eliminate markets but to decrease the marginal return on private spending by ensuring that public services are credible and plentiful. When parents see that they don't need to spend hundreds of dollars a month starting in preschool to keep pace, their thinking about having a second child will shift.

The fourth step involves redesigning parental leave to change who provides care. The data are stark: most OECD countries offer significantly shorter leave for fathers compared to mothers, and uptake often declines when the pay is low or the leave is not reserved. A straightforward solution is to introduce longer, well-compensated, non-transferable leave for partners—12 to 16 weeks at high pay replacement levels—and enforce flexible return-to-work rights. Publicizing firm-level take-up rates will also help. When fathers take meaningful leave, the penalties for mothers decrease. When these penalties lessen, couples are less likely to stop at one child. This is not about cultural rhetoric; it's about changing the structural incentives in both the labor market and the home.

The fifth step is to address the narratives that amplify comparisons. Schools and educational authorities cannot control social media, but they can eliminate rankings in early education. Remove class rankings and selective exams in the primary years. Adjust assessments to focus on growth and equip teachers to discuss progress without promoting a status hierarchy. Public messaging should clearly indicate that success is not defined by what the top decile is achieving. Meanwhile, mental health resources aimed at parents should recognize and validate the anxiety stemming from digital comparisons. Communities that present parent networks as learning commons—with shared resources, collective tutoring, and clear support structures—find it easier to prevent competition from spiraling out of control. The goal is not to reprimand parents; it is to change the environment in which they are striving to do what's best for their children.

A final point on measurement is essential. Much public discussion emphasizes simple correlations—more social connections leading to lower fertility, or increased private education associated with reduced fertility—and draws singular policy conclusions. A more effective approach combines various data sources and quasi-experimental findings. This includes cohort-level fertility models regarding childcare expansions, administrative data linking school admissions changes to housing prices, take-up rates for father-specific leave by income level, and data on net childcare costs during periods for having a second child. Current evidence suggests a consistent pattern: while the desire for children remains strong, the feasibility of having children changes in response to pricing, policies, and societal expectations. When the system forces parents to choose between focused parenting and family size, the latter often suffers. We need to restructure the choices available to parents.

A fertility rate of 1.38 in the EU and 0.75 in Korea shows not only smaller families but also a growing gap between what people say they want and what the system allows. We can spend the next decade throwing money into a leaking bucket, or we can fix the issues that turn community pressure into heavy costs. These include high childcare fees, school access linked to housing wealth, and policies that create unequal care responsibilities. None of this means asking parents to lower their love or ambition. It asks schools, employers, and city planners to stop making good parenting feel like it's at odds with having a second child. Suppose we want more babies without longing for the past or pressure. In that case, we must make it easier to be an average parent, not an extraordinary one. Then we can trust that families will respond to their true desires, as the data suggests. This is the only lasting way to end the competition and create a shared space where comparison helps us grow together rather than apart.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2025, Feb. 26). South Korean births increased last year for the first time in nearly a decade.

Eurostat. (2025, Mar. 7). Record drop in children being born in the EU in 2023; TFR 1.38.

Mahler, L., Tertilt, M., & Yum, M. (2025). Policy Concerns in an Era of Low Fertility: The Role of Social Comparisons and Intensive Parenting (BPEA draft). Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Vol. II): Learning During—and From—Disruption. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2024). Society at a Glance 2024: Fertility trends across the OECD. OECD Publishing.

OECD Family Database. (2023–2024). PF2.1 Parental leave systems; PF2.2 Use of childbirth-related leave; Net childcare costs indicator. OECD.

Pew Research Center. (2025, Apr. 22). Teens, Social Media and Mental Health.

Statistics Korea (KOSTAT). (2025, Feb. 26). Preliminary Results of Birth and Death Statistics in 2024.

Statistics Korea (KOSTAT). (2024–2025). Private Education Expenditures Survey of Elementary, Middle and High School Students.

The Korea Times. (2024, Mar. 14). Private education spending in Korea hits fresh high in 2023 (citing Statistics Korea).

The Financial Times. (2025, Mar. 16). South Korea's academic race pushes half of under-6s into 'cram' schools.

The Guardian. (2025, May 17). 'Rethink what we expect from parents': Norway's grapple with falling birthrate.

Reuters. (2024–2025). South Korea's fertility rate dropped to 0.72 in 2023; rose to 0.75 in 2024.

The Ohio State University. (2023, Jan. 12). Falling birth rate not due to less desire to have children.

Comment