When the Buffer Runs Thin: Vietnam’s Public-Sector Ceiling and the Quiet Shift of Korean Capital

Input

Modified

Vietnam’s public sector still drives too much of the economy, squeezing buffers and deterring investors Korean firms are diversifying as energy shortages, tariff shocks, and policy delays raise risk Cutting state dependence and upgrading power and skills can keep capital anchored

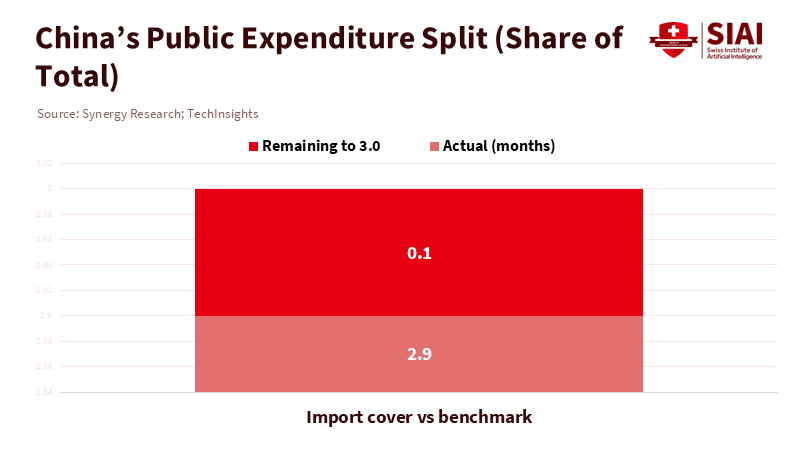

Vietnam’s foreign-exchange reserves dropped to about US$83 billion by July 2024, covering only around 2.9 months of imports. This is below the three-month level that emerging markets view as a safety net. While this figure may seem technical, for factory managers in Bắc Ninh or Thái Nguyên, it signals trouble: thinner buffers lead to a weaker currency, stricter credit, and more unpredictable policies as the state relies on banks to maintain stability. That same year, the government asked major manufacturers in the north to reduce electricity use after last summer’s blackouts. This highlights that infrastructure and governance—not wages—now drive growth. In simple terms, when risks shift from companies to the public sector, mobile capital tends to move elsewhere. Some Korean companies are already diversifying their production and investment outside Vietnam, not because Vietnam has lost its low-cost edge, but because reliance on the public sector is creating more uncertainty than private capabilities can handle.

Vietnam's impressive growth was built on sound macro policies, export-oriented manufacturing, and openness to foreign direct investment. None of this changes overnight. Realized FDI reached about US$25.3 billion in 2024, increasing nearly 10% from the previous year, and South Korea remained one of the top sources of new capital. However, beneath the surface, the nature of risk is shifting. The dong has fallen over 10% against the dollar since 2022, reserves have stayed below safe levels, and the connection between fiscal policy and energy has forced the state-owned Electricité du Vietnam (EVN) to run its coal plants while also considering price reforms to cover losses—necessary actions that still raise production costs and uncertainty. These issues are not about wages; they reflect problems with state capacity, which arise just as new U.S. tariffs threaten to shave off as much as US$25 billion—about a fifth—of Vietnam’s exports to the U.S., increasing the emphasis that firms place on stability.

If we want to keep the Korean capital integrated into Vietnam’s value chains, focusing solely on cost competitiveness misses the point. The real issue is a public sector that still controls too much finance, energy, and permits, and whose inefficiencies now lead to production delays, cash flow problems, and capital budget deferrals. This is what Korean executives notice when they minimize their exposure to Vietnam by expanding in India or Indonesia: it isn’t an ideological shift away from Vietnam, but a form of insurance against potential state-driven disruptions. The potential for growth in these countries should be seen as an opportunity for the future.

Dependency’s domino effect includes credit, power, and administrative burdens

Vietnam's state-owned presence, though smaller than China’s, remains significant in key areas. State-owned banks account for roughly 40% of banking assets, and sectors such as telecoms are still primarily controlled by state firms. When growth targets rise or exchange-rate pressures increase, policies often travel through these state channels—credit quotas, directed lending, and delayed price reforms—heightening the risk of misallocation and squeezing private balance sheets. The outcome is not a swift crisis but a gradual loss of predictability that pushes multinational companies toward operations in multiple countries. This is not just theory; it is evident in the investment data. In 2024, Vietnam missed out on a US$3.3 billion Intel expansion after refusing a cash-support request. It lost an LG Chem battery project to Indonesia. Meanwhile, Samsung looked into ways to shift some U.S.-bound smartphone production away from Vietnam to manage tariff and supply-chain risks—key moments that signal a shift, even though Vietnam remains a central base. Each of these decisions is minor on its own; together, they create a protective strategy against policy and infrastructure challenges.

Energy reliability is at the core of these challenges. The blackouts in 2023 that affected the northern industrial belt impacted campuses and cleanrooms alike; a year later, authorities once again urged major electronics suppliers to cut power use by up to 30% during peak times. Coal's share in electricity generation rose to nearly three-fifths by early 2024, ensuring a consistent supply, while EVN’s accumulated losses prompted regulators to consider further price increases. These moves make sense from a system perspective. Still, for export manufacturers, they lead to unplanned downtime, reduced contracted power, and increased unit costs, especially in energy-intensive sectors such as semiconductors and precision components. Further down the supply chain, smaller Korean vendors with tight margins are the first to delay expansion or look for alternative sites.

Regulatory uncertainty adds to the hardware issues. Proposed rules this month would require police approval for a broad range of investment projects, including those in energy and industrial parks, citing national security concerns. Meanwhile, Europe is urging Hanoi to remove administrative barriers that are choking EU exports. At the same time, Vietnam negotiates new trade agreements to mitigate U.S. tariffs. Investors do not need to read through every regulation to react; they respond to bottlenecks when it comes to permits and ports. For Korean companies accustomed to working with Vietnam’s central agencies, the emergence of veto points across different ministries signals that deal timelines will lengthen and compliance costs will rise. This isn't a story about ideology. It’s a story about transaction costs and about how reliance on the public sector amplifies those costs.

None of this implies that Korea is abandoning Vietnam. Quite the opposite; cumulative Korean FDI remains near the top, and in 2024, Korea ranked second among new capital sources with around US$7 billion. However, the new attitude from Korean firms is cautious rather than focused on broad expansion. New projects are being directed to areas with reliable energy, predictable rules for approvals, and sufficient macroeconomic buffers to absorb shocks from tariffs and currency fluctuations without necessitating drastic policy changes. In this context, Vietnam now competes with India's incentive-driven clusters and Indonesia's battery ecosystem, not just with China’s coastal provinces.

What capital flight signifies for education

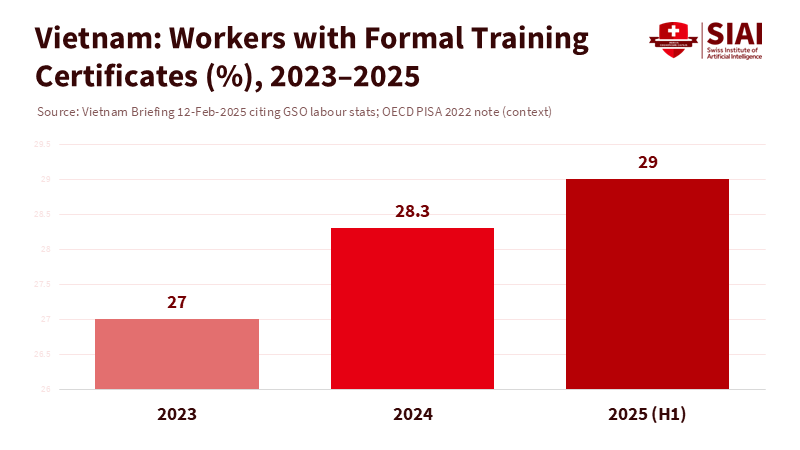

An education journal could rightfully ask: What does this have to do with schools? The answer is clear. When the government carries too much operational risk in the economy, three damaging consequences emerge for human capital development: public budgets lean towards emergency management instead of improvements; companies seek adaptable skills to cope with system volatility; and families respond by investing in credentials that target current employment rather than future capabilities. Vietnam's base level of skills is improving, but it's not increasing fast enough to cope with the upcoming volatility. PISA 2022 placed Vietnamese 15-year-olds at or just below the OECD average in math, reading, and science; this is encouraging, but it does not provide a competitive edge. Only about 28–29% of workers held formal training certificates in 2024–2025, representing a slight annual increase but still significantly below the levels typically found in high-value manufacturing regions. When blackouts or tariff changes occur, companies can't afford to mentor; they instead hire experienced workers or turn to automation. This is how macroeconomic shocks resonate in school hallways.

The lesson for policy is not to initiate another skills initiative but to minimize risk in the system so that training can take root. Three factors are crucial. First, stabilize macro buffers and limit administrative discretion. The government should keep reducing its own size—Hanoi's plan to decrease public-sector staffing by about 20% is a start—but the savings must be allocated explicitly toward reliable electricity (transmission, dispatchable capacity, and demand-response in industrial zones) and an independent regulator that speeds up price reforms with targeted social support. Every kilowatt-hour scheduled on time translates into an hour of on-the-job training preserved. Second, treat FDI policy as a skills policy. When Vietnam loses an Intel upgrade or an LG battery facility, it loses not only capital but also the "learning through doing" process in engineering and vendor development that schools cannot replicate. An open incentive fund that rewards measurable knowledge transfer—mandated apprentice ratios, shared labs, and co-designed curricula—will be far more effective than ad-hoc cash support. Third, enhance foundational skills. Universities and vocational training centers should shift from "training for the last investor" to "training for volatility": power electronics technicians capable of working across coal, gas, and solar; process control engineers who can adjust production lines after supplier changes caused by tariffs; procurement analysts able to model cost fluctuations and provide hedging options. This is not an expansion of the mission; it is essential training for an unpredictable era.

Educators hold significant power, even before the next budget is finalized. The curriculum should develop “system awareness” instead of focusing solely on narrow technical skills. A sophomore course that combines statistics with supply-chain risk and energy economics will be more effective in retaining Korean vendors in Bắc Ninh than yet another generic data-science elective. University-industry councils should shift from formalities to contracts, ensuring paid apprenticeships tied to measurable results, such as the percentage of graduates placed in energy-dependent sectors, the average time to productivity in surface mount technology lines, and the share of capstone projects turned into vendor-approved standard operating procedures. For administrators, the key performance indicator should not be the number of messages of understanding signed. Still, the amount of downtime saved for partner firms during the next power crisis. The World Bank’s note that growth slowed amid global trade uncertainties doesn't call for retrenchment; it should prompt a redesign of education that builds resilience so that when macro buffers tighten, human capital strengthens.

From dependency to capability: a compact for skills, energy, and finance

Vietnam doesn’t need to imitate Greece’s painful adjustments from the 2010s to grasp how reliance on the public sector can hinder growth. It only needs to monitor its own indicators. When foreign-exchange buffers drop below three months' worth of imports, when energy rationing recurs during high-demand seasons, when new regulations shift more investment approvals toward security reviews, private capital clearly understands the message: production risk is transitioning from factories to ministries. Korean companies are not retreating; they are shifting from concentration to diversification, with project committees now asking tough questions that would have been unthinkable five years ago. The response from policymakers cannot be to court each investor with customized subsidies. Instead, it must focus on streamlining the public sector so private capabilities can take the forefront. This begins with fulfilling the promised 20% headcount reduction, earmarking the savings for grid reliability and independent regulation, and narrowing the areas where state banks and state-owned enterprises are the default allocators. It means formulating investment rules that clearly and strictly define where security reviews apply, allowing approvals to become a scheduled item rather than a matter of chance.

For educators, the agreement is straightforward. If Vietnam wants its FDI engine to continue running, schools must produce talent ready for instability: technicians knowledgeable about load-shedding protocols and backup power logistics; engineers skilled in supplier requalification and redesign due to tariff impacts; and managers capable of translating macroeconomic signals into factory-level adjustments without damaging morale. Vietnam’s strengths, as indicated by PISA, provide a solid foundation; its university and vocational systems have begun moving towards industry-focused models, but progress must accelerate and focus on outcomes that matter for production, not just campus metrics. In a world where tariffs can wipe out one-fifth of a key export market and a heatwave can halt production, safety margins must not rely solely on the central bank’s reserves—they must also come from a graduating class that can navigate challenges without waiting for directions.

The initial figure of 2.9 months of imports was not a sign of an impending crisis. It served as a reminder that buffers provide time, and time is necessary to transform public aspirations into private capabilities. Suppose Vietnam uses this time to streamline the state, eliminate bottlenecks crucial to factories, and integrate education with the core of production. In that case, the Korean capital will continue to invest in Vietnam because risks will be assessed, not merely guessed. If there is hesitation—if energy remains constrained, approvals lack clarity, and administrative decisions control finance—diversion will shift to relocation. The choice is not between a “large state” and “foreign capital”; it is between a government that alleviates risks in learning and one that hoards risks until investors seek safety elsewhere. The nation that turned rice paddies into global supply chains can make the right choice. It just needs to view grids, regulations, and graduates as a united policy challenge—and act quickly to resolve it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AMRO (ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office). Vietnam—Annual Consultation Report 2024.

East Asia Forum. “Vietnam’s development model is running out of road.” 22 September 2025.

France24. “‘Revolution’: Communist Vietnam seeks to cut 1 in 5 govt jobs.” 10 February 2025; and “Worry, confusion as Vietnam slashes public jobs.” 28 February 2025.

IMF. World Economic Outlook, April 2025 (context on global trade uncertainty and Vietnam's macroeconomic backdrop).

OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Viet Nam 2025

Reuters. “Vietnam’s power blackouts hit multinationals in manufacturing hubs.” 5 June 2023; “Apple supplier Foxconn asked to cut power use in Vietnam.” 21 May 2024; “Vietnam boosts coal imports … promises no more power cuts.” 26 March 2024; “Vietnam considers rule change allowing EVN to raise power prices.” 18 August 2025.

Reuters. “Vietnam misses out on Intel, LG Chem investments due to lack of incentives.” 5 July 2024; “What Samsung and Vietnam stand to lose in Trump’s tariff war.” 12 April 2025.

Reuters/UNDP. “Hardest-hit Vietnam risks losing $25 billion from U.S. tariffs.” 22 September 2025.

Vietnam General Statistics Office / National Statistics Office. “Socio-economic situation in the fourth quarter and 2024.” 6 February 2025.

Vietnam Ministry of Planning and Investment (Foreign Investment Agency). “FDI attraction in 2024.” 9 January 2025.

Vietnam Briefing (Dezan Shira & Associates). “Vietnam’s 2025 Job Market: Opportunities and Challenges.” 12 February 2025.

World Bank. “The World Bank in Viet Nam—Overview.” Accessed September 2025.

Comment