From Cheaper Capital to Smarter Risk: Capital Market Integration Sparks Europe’s Quality Revolution

Input

Modified

Europe must shift from cheap capital to quality allocation Skilled investors channeling funds to R&D lift productivity and GDP far more than lower spreads Deliver it with a safe asset, harmonised disclosure, scale-up capital, and university pipelines that measure quality

A single number highlights the stakes of Europe's capital-market reform: 110%. This is the penalty the EU's financial services chief described as a "tariff" due to the fragmented rules across member states. It represents an invisible charge on raising and allocating capital that increases every time firms, funds, and savers cross borders. If integration lowered prices, that would matter. However, the greater reward is different. In modern markets, the real challenge is not just about how cheaply money can be offered; it is about who can direct it to the few projects that have the ideas, talent, and execution capabilities to manage risk. When capital market integration is done correctly, it not only heightens price competition for funding but also fosters greater efficiency in the allocation of resources. It spurs quality competition among allocators. This creates a race, similar to Sutton's model, where investors intensify their efforts in discovery, data, and expertise to secure better opportunities. Europe faces a clear choice: continue paying an unofficial tariff and compete on price, or create an integrated space where skilled capital can discover, finance, and expand the continent's best ideas.

From Price to Quality: What Integration Really Changes

Undergraduate industrial organization teaches Cournot for quantities and Bertrand for prices. John Sutton introduced the third component—quality competition—demonstrating why firms invest significant resources in R&D, design, data, and branding to enhance willingness to pay. The outcome is a market where a few high-quality players secure lasting profits while low-end producers compete on price. Investment allocation works similarly. If a capital market only lowers issuance spreads and transaction costs, we observe a Bertrand-like "price effect." However, if integration also attracts and enables allocators with genuine skills—such as domain networks, technical diligence, and operational playbooks—it activates Sutton's mechanism on the demand side. Investors will spend more on research and capability to secure deals, ensuring that the additional euro is likely to support innovation rather than inertia. In simpler terms, integration is a policy change that shifts Europe's finance from a price-based competition to a quality-based competition, marking a significant shift in the industry's focus.

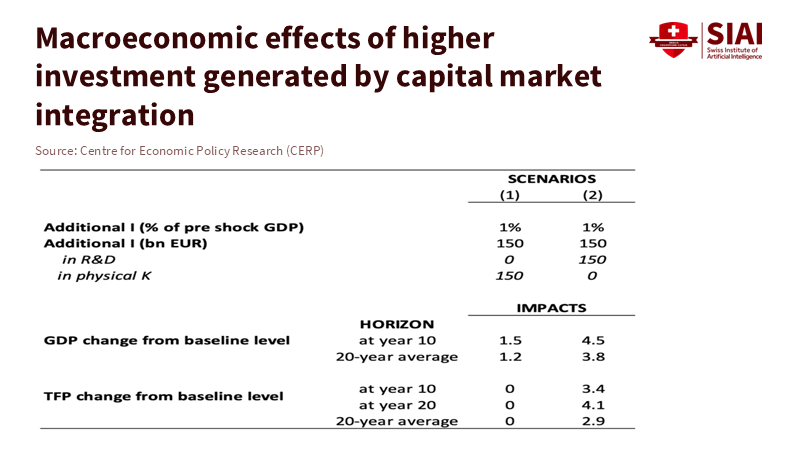

This is precisely the new perspective recent macro modeling proposes. A new VoxEU analysis calibrates a euro-area dynamic equilibrium model with two types of capital—physical and R&D. Greater integration decreases the cost of capital by about 50 basis points (the price channel) and, even with cautious assumptions, raises output by around 1.5% over ten years if the extra investment goes to tangible capital alone. However, when the same marginal euro is directed to R&D, the model's quality channel—representing skilled, risk-tolerant capital—boosts total factor productivity by 3–4% and raises GDP by 4% in ten years and 6% in twenty. It also adds an extra 1.6% of GDP from a realistic reduction of the EU–US VC gap. In simpler terms, quality allocation is more important than cheap allocation. That concept reflects Sutton's principles in macro terms.

Europe's innovation landscape reinforces this point. The EU's ICT software sector invested under €20 billion in industrial R&D in 2023, compared to over €180 billion in the US—a significant gap in a field where allocator skill and network advantages are crucial. Still, progress is evident: the EU's 2024 Industrial R&D Scoreboard shows that EU firms increased R&D spending by 9.8% nominally in 2023, outpacing the US and China for the second consecutive year. Meanwhile, AI-related patent filings at the EPO rose 10.6% in 2024. When quality investment emerges, it compounds; when it is scarce, price competition prevails and progress shifts elsewhere. Integration is the lever that promotes quality and limits the latter.

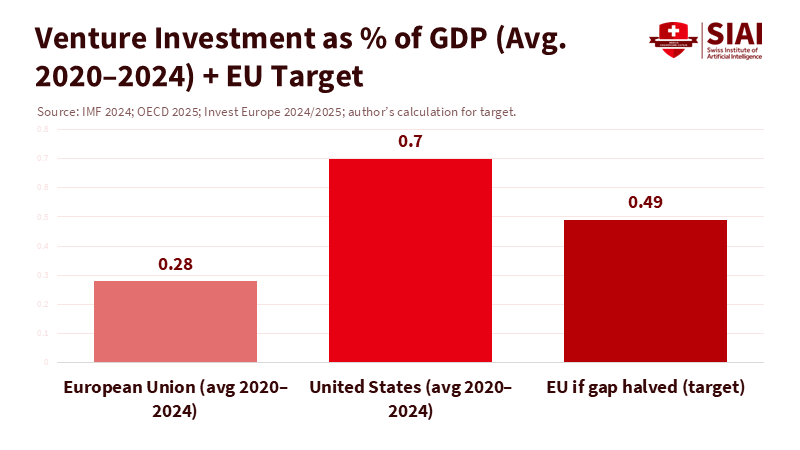

Evidence Since 2023: Where Alpha Chased Quality

To assess the "quality effect," we can look at risk capital. Over the last decade, EU venture investment has averaged approximately 0.2–0.3% of GDP, while the US has averaged around 0.7%. The tightening in 2022–2023 affected both sides of the Atlantic; however, Europe's lower starting point and thinner late-stage pools meant that many promising firms stalled or relocated. The lesson is not that Europe lacks ideas; rather, it is that skilled allocators struggle to scale within a fragmented system. The policy response is finally coming together: the Commission's Savings and Investment Union strategy places capital market deepening at the heart of competitiveness. Seven member states have launched a pan-European savings label to encourage household investments in European equities, and Brussels is promoting a Scale-up Europe Fund, expected to exceed €10 billion, to bridge late-stage funding gaps. Each of these measures addresses different challenges, and together they begin to prioritize quality over price, emphasizing the crucial role of skilled allocators in scaling Europe's ideas.

The missing element has always been macro plumbing. Europe's fragmented market structure imposes convenience fees and legal complications unevenly across borders. An integrated market—potentially supported by a credible European safe asset—does more than reduce spreads; it standardizes benchmarks and collateral systems, allowing specialist investors to apply high-skill, high-effort strategies on a large scale. The ECB has noted the changing dynamics of the "convenience yield" and its connection to long-term rates. The VoxEU model, in turn, attributes about half of the 50-basis-point decline in the cost of capital to the rise of such a common safe asset. This creates conditions for Sutton-style quality competition on the buy side. If allocators can depend on deeper secondary markets and uniform disclosure, they can devote more fixed effort per euro in search of genuine alpha, rather than just exploiting paperwork.

Of course, critics express concerns that quality competition leads to concentration and neglects smaller markets. Sutton's theory acknowledges this: when firms—or allocators—compete on quality by increasing their fixed investments, concentration can increase. However, the welfare perspective is broader. Concentration stemming from superior R&D, design, and expertise can enhance consumer welfare even when price competition decreases, as willingness to pay shifts in response to quality improvements. In capital markets, the parallel is clear: a continental group of skilled investors supporting pioneering projects across borders may reduce the number of dominant allocators, but it increases the spillovers from their portfolio companies—technology diffusion, supplier advancement, and labor-market mobility—especially if policies ensure competitive conditions at the interface with entrepreneurs. The alternative is a large, fragmented pool of low-effort money investing in safe assets while progress occurs elsewhere.

What Schools Should Do Now

Education policy is where Europe can most quickly shift its focus from one on price to one on quality. Curricula should extend beyond Cournot versus Bertrand to teach Sutton's quality competition as a core concept for an innovation economy. This entails training students—not only in business schools, but also in engineering, data science, and public policy—to comprehend fixed investments: how much effort to dedicate to discovery, validation, and design before any product is sold. It also involves clarifying the capital aspect: how allocators build and utilize informational advantages, and why integrated markets enhance those advantages for the public good. A program that combines industrial organization with applied finance, patent analytics, and open-data knowledge would prepare graduates to either boost R&D productivity within companies or to evaluate it credibly as allocators. Without that skilled workforce, even well-functioning capital-market structures will funnel too much money into simpler areas of the market.

Universities and ministries can take action now with low-risk pilot projects. First, establish pan-EU capstone allocation labs that supervise student teams in sourcing and screening cross-border projects based on clear R&D and IP metrics from the EPO and the EU R&D Scoreboard, and publish performance dashboards that build local reputations for quality. Second, create teaching funds—small, regulated entities that co-invest alongside accredited partners to support late-seed and Series A teams emerging from labs and research centers, with strict transparency and conflict-of-interest rules in place. Third, standardize spin-out procedures and founder equity norms across public universities to reduce negotiation obstacles that deter outside investors. Finally, embed criteria into assessments: every funded project should outline expected intangible benefits, timelines for technical validation, and a clear link from R&D to profit growth—conditioning students to think like producers and allocators in Sutton's framework.

Since finance students will populate the Savings and Investments Union in practice, programs should teach the structures alongside the principles. Courses on insolvency harmonization, listing requirements, and supervisory alignment should connect to the Commission's SIU communication, while seminars on safe assets and convenience yields should follow the ECB's evolving analysis. The goal is not to turn classrooms into regulatory training grounds; it is to prepare graduates to build market interfaces that facilitate quality competition. A generation that can connect micro-theory, macro-tools, and legal intricacies will identify where a brief change in a prospectus rule or a passportable sandbox can reduce hurdle rates by ten basis points or improve total factor productivity by two percentage points in ten years. This is the skilled workforce that the Capital Market Union truly needs.

Building Skills and Trust for a Quality-Driven Market

If administrators seek a practical target, begin with measurement. Track, at the program and regional level, three indicators: i) the share of graduate-founded companies whose first funding round includes an investor from another EU country; ii) the share of university-affiliated projects with R&D intensity above their sector median at the time of initial equity; and iii) the 36-month patent-to-product conversion rate for funded projects. None of these requires new legislation; only collaboration with existing data sources is needed. They reflect precisely what quality competition aims to change: where money flows, how risky the funded pipeline is, and whether those risks yield results in the market instead of just in grant reports. As the Commission's proposals progress and savings labels promote household investments, these indicators will indicate whether integrated markets reward quality or merely lower price competition.

Europe's educators also have a storytelling role. Students should hear consistently that the goal of integration is not to enrich financiers or comfort issuers; it is to make innovation trustworthy. When skilled allocators are visible, accountable, and prepared to explain their methods—what they considered, why they declined specific options, how they assessed risk—society is more willing to accept risk and failure. This cultural change does not happen automatically. It requires a teaching approach that values clarity over jargon, evidence over feelings, and cumulative understanding over hero narratives. In a Sutton world, the winners are those who spend wisely on quality; in a democratic market, the winners are those who can also articulate that spending publicly. Europe's classrooms can model that discipline today.

The 110% "tariff" metaphor hits hard because it simplifies a complex institutional problem into a figure everyone understands. Yet, it also obscures a larger truth. Fragmentation is not just costly; it is misdirecting Europe's limited risk capital away from the work that drives progress. The argument for a Capital Market Union was initially framed around marginal efficiency: lower spreads, cheaper listings, and fewer forms. Today, the case centers on who is allowed to compete and how they do so. Suppose integration uplifts Europe's best allocators and compels them to out-invest each other in discovery and judgment. In that case, the macro benefits models associated with R&D will stop being theoretical and start appearing in classrooms, labs, and payrolls. We can either continue paying the tariff and competing on price, or we can complete the task and transform Europe's capital market into a contest of quality. The first path is familiar. The second is more challenging—and it is precisely what an education system worthy of its students should teach us to create.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Accenture (via Reuters). AI, cloud funding in US, Europe and Israel to hit $79 bln in 2024, Accel says. 16 Oct 2024. (context on AI investment trends).

Bank of Finland. Is the euro area investing enough? Bulletin 1/2025. (investment and VC share context).

BIS (Nenova, T.). Global or regional safe assets: Evidence from bond portfolio rebalancing. Working Paper No. 1254, 2025.

ECB (Schnabel, I.). No longer convenient? Safe asset abundance and r. Speech and annex, 25 Feb 2025.

EIB. Investment Report 2024/2025: Innovation, Integration and Simplification in Europe. 2025.

EIB. The scale-up gap: Financial market constraints holding back EU firms. 2024.

EPO. Patent Index 2024 (overview and AI insight pages). 2025.

European Commission. Savings and Investments Union—Communication COM(2025) 124. 19 Mar 2025.

European Commission JRC (Nindl et al.). The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard. 18 Dec 2024.

IMF. Stepping Up Venture Capital to Finance Innovation in Europe. 12 Jul 2024.

Invest Europe. Investing in Europe: Private Equity Activity 2023. 7 May 2024; Private Equity Activity 2024. 8 May 2025. (aggregate PE/VC activity).

OECD. Economic Surveys: European Union and Euro Area 2025. 19 Jul 2025 (VC as % of GDP).

Reuters. EU financial services fragmentation works as 110% tariff—Albuquerque. 7 Jan 2025.

Reuters. EU plans tech scale-up fund to narrow gap with US, China. 28 May 2025.

Sutton, J. Sunk Costs and Market Structure. MIT Press, 1991; Technology and Market Structure: Theory and History. MIT Press, 1998 (see publisher pages for overviews).

VoxEU/CEPR (Venditti, Caivano, Cova, Pallara, Pisani). The economic impact of European capital market integration. 22 Sep 2025.

Comment