When “looking through” looks away: inflation’s surprise, welfare loss, and what schools needed from monetary policy

Input

Modified

Forecast errors turned a supply shock into larger welfare losses; “look-through” amplified them Make look-through state-contingent with public shock decompositions and automatic triggers Shield schools via indexed budgets, pooled energy hedging, and efficiency investments that cut volatile costs

In 2021 and early 2022, major forecasting agencies across Europe, including central banks, significantly underestimated inflation. The European Central Bank’s own assessment states that all forecasters significantly underestimated inflation during 2021 and the first quarter of 2022. This was not a minor error; it was a serious oversight. Expectations were based on decades of stability, but they were faced with a supply shock driven by war. This shock affected gas and electricity markets, as well as food and freight. When the initial facts are incorrect, a “look-through” strategy—essentially, a wait-and-see approach—does not lower costs; it raises them. Schools and universities experienced this firsthand. Energy bills surged before budgets could adjust, wage talks lagged behind rising prices, and procurement contracts were made out of fear. Misjudging the shock led to widespread effects, from interest-rate decisions to cafeterias and classrooms. The lesson is clear and harsh: when information is inadequate, “looking through” is not neutral. It imposes welfare losses on those who cannot protect themselves.

The hidden cost of getting the shock wrong

Monetary policy is not just about where rates end up; it’s also about how far off we are along the way. In typical economic models, the welfare loss that central banks aim to minimize depends on how far inflation and the output gap stray from their targets. In simple terms, being wrong hurts more than expected; doubling the error results in more than double the loss. If you mistakenly think a supply shock is temporary, a look-through approach allows inflation to rise while real economic activity struggles, and the losses grow with each passing month; you are mistaken. This theory is not new. It’s well-established in the literature that supports practical rules. One of them is the Taylor rule, a monetary policy rule that stipulates how much the central bank should adjust the nominal interest rate in response to changes in inflation, output, or other economic conditions. The Taylor rule responds to both inflation and activity gaps, as welfare relies on both, and significant misalignments are costly. When these gaps occur because expectations were tied to the wrong shock, a small initial error can lead to a hefty social cost—spread across public services, including education.

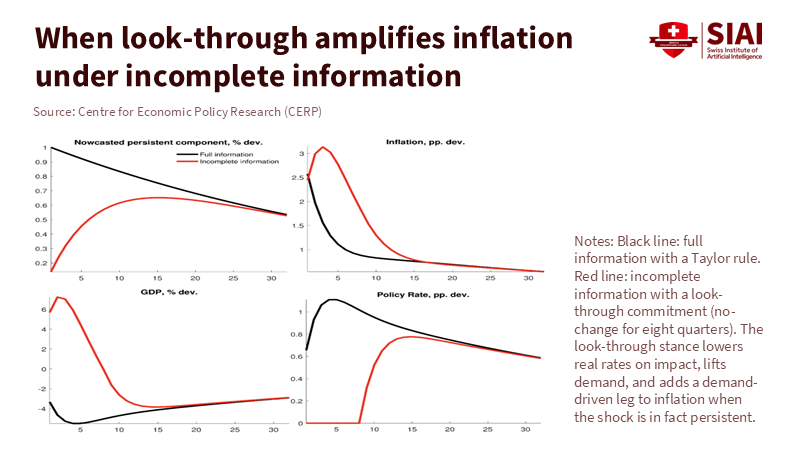

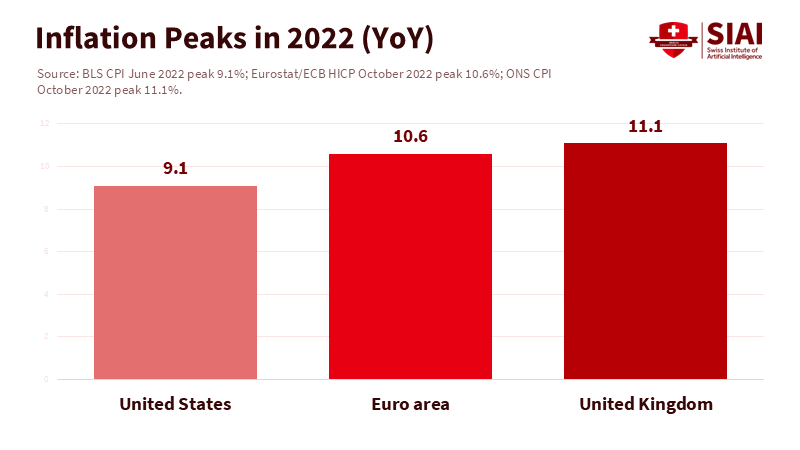

Proactive fiscal measures can mitigate impacts on schools. The recent return to the “look-through” strategy has been met with criticism. The approach originated from the oil shocks of the 1970s and 1980s as a means to manage sudden price increases while maintaining stable expectations. Ideally, a central bank tolerates the initial spike driven by energy, communicates clearly, and avoids tightening too much during a supply squeeze. But this logic assumes the central bank can quickly and accurately identify the shock. Recent research suggests that, with incomplete information, “look-through” can backfire: if the shock is misidentified, policies that allow initial inflation may disrupt expectations and worsen real outcomes. This is not just theoretical. During 2021-2022, forecasters underestimated both the scale and duration of rising inflation. By mid-2022, U.S. CPI inflation had reached 9.1% year-over-year, the highest level in four decades, and the euro area peaked at 10.6% that same month. When you “look through” the wrong issue for too long, you do not buy time; you end up with a more costly adjustment later.

Central banking during that period was challenging in ways few policymakers had ever encountered. The key question isn’t whether rates should have been higher earlier. It’s whether the available information and tools for identifying shocks were practical. On that front, recent literature makes it clear: early supply factors played a significant role and were unusually difficult to interpret. Analyses by the IMF and BIS show that supply-driven inflation surged in 2022, especially in Europe. In such scenarios, traditional demand-side tightening primarily works through patience and credibility, doing little to increase gas supply, clear ports, or restore lost crops. A look-through strategy may be valid if you are certain. If not, the anticipated welfare benefits from waiting must be weighed against the possibility that the shock is much larger and more persistent than thought. In 2021-2022, that risk was not taken into account.

Why supply shocks break our thermometers

Forecasts failed because the shock itself disrupted the factors that make forecasts reliable. Europe’s benchmark TTF gas price soared above €300 per MWh in August 2022, nearly ten times its pre-crisis range—prices that are notoriously difficult to include in medium-term models without distorting them. Oil prices briefly exceeded $120 per barrel in mid-2022 as markets reacted to the invasion of Ukraine and its ripple effects. When a key input’s price skyrockets, filters set to decades of stability try to pull it back down. That’s precisely what happened in 2021-2022: both the ECB and the U.S. Survey of Professional Forecasters consistently predicted a quicker decline in inflation than occurred. Even into 2024-2025, officials continued to revise projections downward, underscoring that the data generation remained unsettled. A shock of that magnitude, defined by geopolitical factors, resists precise predictions; treating it like a typical demand fluctuation was a significant error.

If misdiagnosis was the first issue, spillovers were the second. The early 2022 energy shock spread beyond its initial scope. It affected food, transportation, and durable goods through rising costs, and subsequently impacted services through increased wages. Research by central banks and international organizations indicates that supply factors initially dominated, with demand factors becoming more prominent later as fiscal support and reopening dynamics increased spending. By late 2023 and into 2024, measured inflation dropped sharply, but core pressures remained persistent, reflecting a shift from energy to labor-intensive services. This situation is where a quick look-through approach under incomplete information can do the most damage: you wait through the supply spike, but by the time demand takes over, you need a quicker reaction to avoid continued inflation—and you have less credibility and more accumulated losses to deal with.

Misjudging shocks can have a significant impact on public sector finances. The ECB’s significant losses in 2023-2024, partly due to interest expenses on bank reserves following rapid rate hikes, demonstrate that when rates must rise late and significantly, the financial repercussions can be severe. Losses do not stop a central bank from fulfilling its mandate, but they influence the political aspects of policy choices and impact public finances that support schools and colleges. In this context, the welfare loss from misperception is not just an abstract concept; it directly affects the budgets that fund classrooms, labs, and buses.

After the shock: a better playbook for classrooms and rate-setters

The education sector is where macroeconomic errors become very personal. Teacher pay has lagged for years, and inflation has widened the gap: U.S. K-12 teachers earned about 27% less per week than similarly educated workers in the 2023-2024 school year, marking the most significant gap on record. School nutrition directors reported sharp cost increases and the return of unpaid meal debt as pandemic waivers ended. Even as overall inflation eased, districts struggled with rising energy and transport costs linked to contracts signed during price spikes. It’s not enough to say “inflation is falling.” Public services require a structure that maintains introductory provisions stable when forecasts fail. This calls for budget rules that include state-contingent safeguards, such as automatic increases to per-pupil grants linked to a select group of energy and food prices; rapid procurement options that allow for quick rebidding when set price thresholds are reached; and pre-approved wage adjustments that kick in when forecast errors surpass certain limits. These measures are not optional; they are essential for a realistic monetary strategy that acknowledges when predictions are uncertain.

There is good news: we now have the tools to see changes in supply and demand in near real-time. The Shapiro decomposition for U.S. PCE inflation, adapted by the BIS and ECB, separates categories where prices and quantities rise together (demand) from those where they diverge (supply). This is not a perfect solution, and the methods have limitations; however, it represents a significant advancement from the vague approaches used in early 2021. Central banks should regularly publish a supply-demand analysis alongside rate decisions and connect their guidance to it: “We will consider looking through only if supply factors dominate and expectations remain stable, as indicated by X, Y, Z.” These indicators should include forecasting errors themselves; when the median prediction consistently falls short, the threshold for look-through should increase. Communicating this framework would not only improve the timing of policy decisions but also provide finance ministries and school boards with a basis for their own safeguards.

On the fiscal side, governments should stop unintentionally expecting schools to navigate energy markets. The UK’s Energy Bill Relief Scheme and its successor discounts were blunt, temporary measures that helped keep lights on during the worst of 2022-2023. In the United States, the Department of Energy’s Renew America’s Schools program and the Inflation Reduction Act tax credits created avenues for districts to invest in efficiency, solar, and geothermal systems without needing tax incentives. The lesson is to make these protections standard: establish ongoing programs for public entities to pool energy purchasing and manage price risks; allow automatic, rules-based access to temporary relief when benchmark prices exceed predetermined limits; and connect capital grants to measurable savings in operating costs that can fund future wage adjustments. These policies do not fight against an oil shock; they navigate around it, making cafeterias and classrooms less vulnerable when models fail again.

For central banks, the superior approach is not to eliminate look-through but to structure it wisely. Make it a policy contingent on state conditions with clear safeguards: publish your best assessment of shock causes; define specific thresholds for short-term inflation expectations, wages, and the extent of price changes that, if surpassed, automatically halt look-through; and recognize the increasing costs of welfare losses—errors can become pricey quickly—so the responsibility for inaction rests with those when information is lacking. This aligns with recent research on look-through and incomplete information: the strategy can be effective, but the cost of errors escalates rapidly when supply issues are significant and error margins are broad. If we had insisted on this level of discipline in 2021, the interim social losses felt by schools, hospitals, and households would likely have been minor.

What does this mean for education leaders today? First, budget for the current economic reality, not for an outdated model. Treat energy and food as unpredictable costs that need automatic stabilizers; advocate for rules that provide these. Second, price retention risk is openly discussed. If teacher wages continue to fall behind during the next crisis, the cost to replace educators will add to your real wage savings. Third, ensure that capital investments enhance resilience. Use today’s credits and grants to convert fluctuating operating costs into financed assets—like efficiency upgrades, rooftop solar, and modern HVAC systems—resulting in lower bills in any situation. Policymakers should facilitate these choices by providing standardized contracts, shared procurement services, and transparent reporting to ensure that savings are allocated to education. It’s the practical side of macro stabilization, and it’s essential.

The most significant outcome of the last inflation cycle wasn’t a specific rate; it was the overall forecasting error—the evidence that our prior assumptions were too relaxed for our current reality. We don’t fix this by promising to be bolder next time. We address this by developing a plan that acknowledges we might be wrong again and aims to make being wrong less costly. For central banks, this means publishing analyses of shocks, instituting safeguards for look-through policies, and tightening more rapidly when key triggers are activated. For governments, it means permanently linking school budgets to the first prices that rise during a supply shock and financing improvements that reduce those expenses in the long run. For education leaders, it means advocating for reliable rules rather than temporary fixes. The next shock will differ—by definition. If our expectations are missed, the welfare loss does not have to be. It can be capped by design, keeping teachers in classrooms, buses on routes, and cafeterias serving hot meals while macro policy does its work. That is what we owe students after the loudest lesson inflation could deliver.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2022). “Consumer prices up 9.1 percent over the year ended June 2022.” U.S. Department of Labor.

BIS (2024). Quarterly Review, December 2024—Box A: “Decomposing inflation into demand and supply components.” Bank for International Settlements.

Bušs, G., & Traficante, G. (2025). “The return of inflation: Why ‘look through’ can backfire under incomplete information.” VoxEU/CEPR.

CBO (2025). CBO’s Economic Forecasting Record: 2025 Update. Congressional Budget Office.

Clarida, R., Galí, J., & Gertler, M. (1999). “The Science of Monetary Policy: A New Keynesian Perspective.” Journal of Economic Literature, 37(4), 1661–1707.

ECB (2024). Economic Bulletin Issue 3; and Annual Report 2024—core inflation dynamics. European Central Bank.

European Council (2022). “A market mechanism to limit excessive gas price spikes.” Infographic on TTF peaks.

EPI (2024). “The teacher pay penalty reached a record high in 2024.” Economic Policy Institute.

Firat, M., & Hao, O. (2023). “Demand vs. Supply Decomposition of Inflation: Cross-Country Evidence with Applications.” IMF Working Paper 2023/205.

Federal Reserve Board (2025). Edward Nelson, “A Look Back at ‘Look-Through’.” FEDS 2025-037.

IMF (2025). Laurence Ball et al., “The Rise and Retreat of U.S. Inflation: An Update.” Working Paper 2025/094.

Reuters (2024–2025). Coverage on ECB losses and inflation trajectory.

U.K. Government (2022–2024). “Energy Bill Relief Scheme” and “Energy Bills Discount Scheme” guidance. Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy / HM Government.

VoxEU/CEPR (2025). “The high price of the fight against inflation: The case of the euro area.”

Comment