Teach the Robots, Keep the Republic

Input

Modified

Robots should be Europe’s first responder to ageing, handling routine work so people focus on human-only tasks Education must pivot fast—stackable credentials for robot operation, integration, and safety Use migration where irreplaceable in care and teaching; automate the rest to stabilize growth

The most critical number in Western Europe today is 33.9%. That is the EU's old-age dependency ratio in 2024, which compares the share of people 65 and older to those aged 20 to 64. This figure has risen again this year. In Italy and Portugal, it is already approaching 40% and is set to exceed 60% by mid-century. Europe is also losing about one million workers each year as baby boomers retire. The usual solution is to import labor. However, this approach faces political limitations and practical challenges, even as economies digitize and energy costs transform the industry. Meanwhile, factories worldwide operated 4.28 million robots in 2023. Germany has a robot density of 429 per 10,000 workers, while China has surpassed this at 470 per 10,000 workers. This shows that automation capacity is not just a science fiction concept; it is a reality. Europe's choice is clear: argue endlessly about migration or act quickly to expand "domestic labor" that doesn't vote, age, or require housing—robots—while also investing in human skills to operate them.

We are not suggesting a world without migrants. Europe's services, research, and care sectors will still need people. We are advocating a robots-first strategy for routine work in aging economies, allowing scarce human attention to focus on higher-value tasks. This approach is crucial now because demographic changes are happening faster than integration cycles can be implemented. Political tolerance for large migrations is fragile, even when economic conditions suggest that more labor is needed. Importantly, technology that can automate many routine tasks is becoming increasingly cheaper and more effective each year. The issue is no longer whether robots can substitute; it is whether education systems can produce enough operators, maintainers, integrators, and supervisors quickly enough to turn automation into a stabilizing force for the economy.

Aging Without Anxiety: Make Robots the First Responder

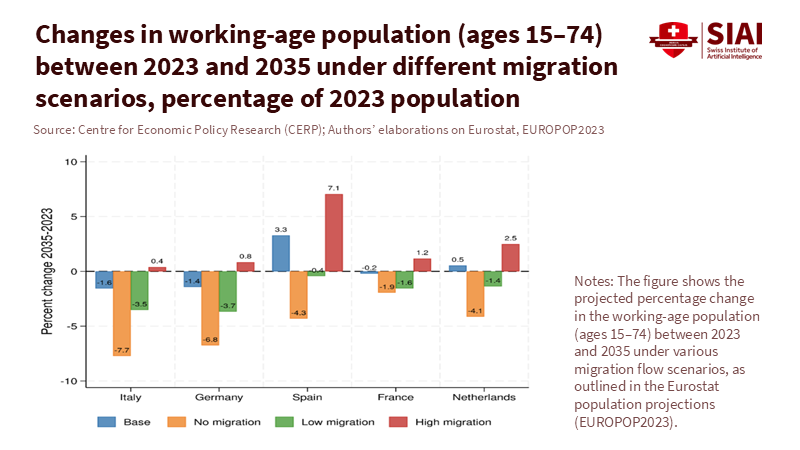

The demographic numbers are unyielding. Eurostat forecasts that by 2050, over a dozen EU countries will have old-age dependency ratios exceeding 50%, with Greece, Portugal, and Italy projected to surpass 60%. This means there will be fewer than two working-age adults for every retiree. The OECD's Employment Outlook notes that the working-age population across OECD countries is expected to shrink by 8% by 2060, and by over 30% in some nations, unless labor participation and productivity increase. In the short term, immigration has helped fill record job openings; however, the scale required to counteract the demographic decline is massive and politically sensitive. A robots-first approach alleviates some of that pressure. Global industrial robot density has doubled in seven years, with installations surpassing half a million annually for three straight years. This situation is not a speculative promise; it represents a deployable resource that can extend beyond the automotive sector into areas such as food processing, logistics, and construction, which are facing persistent job vacancies.

The economic conditions are shifting in favor of Europe. The cost of industrial robots has decreased significantly over the last decade, with industry estimates placing the average unit price near $23,000 in 2022 and predicting further decreases as robotics-as-a-service expands and control systems, sensors, and vision systems become more affordable. Germany already operates more than 429 robots for every 10,000 factory workers. South Korea and Singapore demonstrate evidence of market saturation. Still, for Europe, the message is simple. Every year that European schools fail to graduate technicians skilled in robotics, they push aging companies to delay investments or relocate production to locations where qualified workers are available. Importantly, research shows that older societies do not necessarily grow more slowly; they adopt more automation and maintain output levels. In other words, demographic changes drive technological adoption rather than ensuring economic stagnation. If policies support it, robots can serve as a buffer, buying time for careful, targeted migration where human interaction is most vital.

Where Robots Fit—and Where People Still Matter

The strongest argument for a robots-first approach emerges in areas where tasks are routine, repetitive, and physically demanding. Manufacturing has led the way, but now the focus is moving towards logistics, agriculture, and even aspects of construction and building maintenance—sectors that have high vacancy rates and persistent skill gaps. Eurofound reports that 80% of EU employers struggle to find workers with the right skills. The EURES shortages report highlights that these problems are growing across 31 countries. Europe should intentionally target these shortage areas with job designs that anticipate the use of robots, autonomous guided vehicles, and AI inspection systems to handle baseline operations. Human roles should then shift to managing exceptions, ensuring quality, and interacting with customers. Think of robots as first responders for tasks that don't require human judgment, while workers take on roles as coordinators and problem solvers. The overall outcome won't be fewer jobs but a shift towards different jobs with a higher demand for skills in mechatronics, data management, and workflow adjustments.

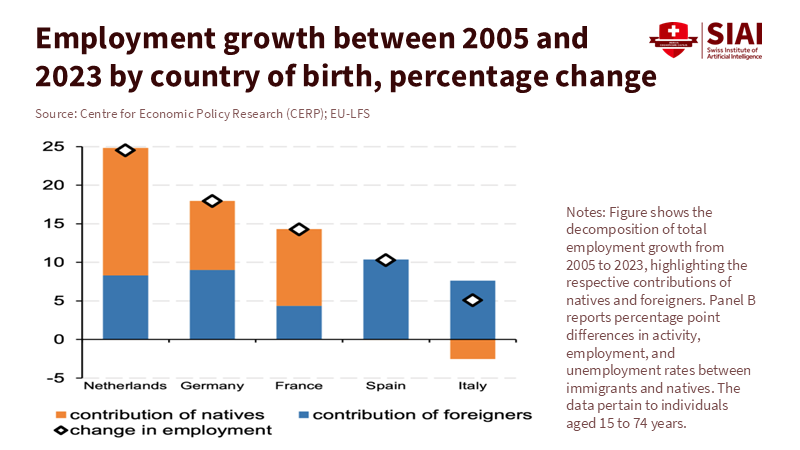

In contrast, care is the most challenging area to automate. However, even here, the proper division of labor can be effective. The EU's joint OECD-Commission review estimates a shortage of around 1.2 million doctors, nurses, and midwives as of 2022, based on universal coverage standards. Japan's nursing homes, facing a steeper demographic decline and strict immigration rules, are experimenting with assistive robotics for lifting, transferring, and monitoring patients. Early results indicate that robots can reduce injuries, free up time for more personal care, and help small staffs manage larger groups. While prototypes are improving, they won't be fully realized before 2030, so planning needs to start now. This principle also applies to classrooms and labs: robots can handle preparations, logistics, and repetitive tasks while teachers focus on providing feedback, mentorship, and project work. In areas where human presence is crucial—such as end-of-life care, early childhood education, and complex teaching—targeted migration remains necessary and financially viable. OECD reports generally show that the net fiscal impact of migration is small and often positive; Spain's budgetary council suggests that recent immigrant groups contribute significantly to net revenues. The goal is not to choose between robots and migrants, but to prioritize robots where feasible and utilize migrants where they are irreplaceable.

Turning the Aging Shock into an Education Mandate

If robots are to be Europe's answer to aging, education must be at the forefront. Three critical shifts are necessary. First, credentialing: develop modular micro-credentials in robot operation, maintenance, safety, and integration that lead to national diplomas. These should be short, portable, focused on assessments, and recognized by relevant stakeholders. The aim is to help a mid-career logistics worker transition to a line automation supervisor in months, not years. Second, placement: connect vocational education and training (VET) systems with employer groups that share training resources and simulation equipment, allowing small and medium-sized enterprises to still train apprentices on standard machinery. Third, curriculum: incorporate AI-driven quality control, digital twins, and safety standards into high school tech classes so graduates can effectively communicate with machines and troubleshoot issues. This approach will help create a larger pool of workers who are skilled in robotics quickly enough to have a macroeconomic impact. Sectors with high vacancy rates, such as construction and ICT, should be the initial focus.

Skeptics raise three valid concerns. Productivity gains may be modest, at least when narrow measures are applied. An IMF working paper estimates a roughly 1% cumulative productivity increase over five years from current AI in Europe under conservative assumptions. However, that is why education is crucial: the adoption of technology often lags, which is typically linked to lags in human capital development. The same IMF analysis reveals that European results vary depending on the adoption scenarios; workforce skills and regulations have a significant influence on this variability. Robots can be costly compared to some wage levels and present challenges in integration. However, costs are decreasing, and business models are shifting towards subscriptions. Europe could accelerate robot adoption by implementing targeted super-deductions tied to training, safety compliance, and domestic rollouts, as well as through "robot sandboxes" that facilitate faster certification processes. Robots are not capable of empathy. This is true, and we shouldn't expect them to be. A robots-first approach is beneficial precisely because it allows human attention to focus where it is most productive: in care, creativity, and complex coordination.

The politics of migration cannot be overlooked. Two realities can coexist: migration has supported much of Europe's job growth and often offers financial benefits, yet depending solely on migration to counteract aging demographics is unlikely due to limitations on housing, schools, and public acceptance. Europe welcomed 5.1 million non-EU immigrants in 2022 as borders reopened, and the IMF found that immigration helped meet unprecedented labor demand during the 2022–23 period. Still, EU officials caution that the working-age population is contracting by about one million each year—a pace that would require similar net inflows indefinitely to maintain current workforce levels. Robots can change this situation; they reduce the number of roles that countries must compete for in the global labor market, creating political space to welcome migrants into roles where they can truly add social value.

Education systems are where these threads intersect. Universities should view automation education as essential rather than as an optional course: every engineer, nurse, teacher, and administrator should graduate prepared to determine which tasks can be "automated now," which should be "co-piloted," and which should remain "human-only." VET colleges should collaborate with national robotics centers to provide traveling labs to remote regions; any town with a makerspace can also host a training facility. Primary and lower-secondary schools should broaden project-based robotics programs that emphasize safety, ethics, and teamwork, not just coding. Workforce agencies should establish pathways for parents and older workers re-entering the labor market, recognizing prior skills and prioritizing short, high-frequency, and underpaid practice over lengthy lectures. Since robot adoption is influenced by management quality, business schools and teacher-training programs should share strategies on change management—how to manage procurement sequences, retrain staff with dignity, and communicate benefits to families and unions.

None of this requires a leap of faith in technology. It demands coordination and urgency. The existing infrastructure is substantial, the pricing trend is favorable, and the demographic challenges are immediate. Futurists warn that robots and AI will impact nearly all jobs within the next two decades. We don't have to agree with every forecast to recognize the risks of inaction. Europe can frame the upcoming decade not as a conflict between locals and newcomers but as a race to make routine work affordable, safe, and plentiful through machines. This will free people—both natives and newcomers—to do the vital, human jobs that enrich societies. This is primarily an educational challenge, not merely an immigration challenge.

A Practical Pact for Ageing Europe

Return to the key number that opens this essay: 33.9% and climbing. If no action is taken, this ratio will exert pressure on schools, hospitals, and local budgets for generations. A robots-first agreement allows us to change this trend. It calls on governments to eliminate hurdles to adoption and fund quick credentialing programs; it asks employers to invest in their workers as they do in their machines; and it encourages educators to make literacy in automation as fundamental as algebra. It also requires us to be honest about migration: to embrace it where human interaction is critical and to allow machines to take over where they can ease the burden. We can transform the challenges of aging into a benefit for human capital if we train millions to specify, supervise, and safely implement robot labor while safeguarding the work that only humans can perform. The alternative is a smaller workforce overwhelmed by demands, with fewer resources to meet them. In that situation, both newcomers and existing residents will suffer. In a robots-first future, Europe can keep its commitments.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2021). Demographics and Automation. Review of Economic Studies (working paper version). https://pascual.scripts.mit.edu (PDF).

AIReF – Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (2025). Box 5: Fiscal Impact of Immigration. https://www.airef.es (PDF).

AP News (2024). The EU loses approximately a million workers per year due to aging; a migration official urges exploring legal options.

ELA / EURES (2025). EURES Report on Labour Shortages and Surpluses 2024. European Labour Authority. (PDF).

Eurofound (2024). Company practices to tackle labour shortages.

Eurofound (2024). Living and working in Europe 2024—Chapter 1: Shortages dominate labour market concerns.

Eurostat (2023). Population projections in the EU. Statistics Explained.

Eurostat (2024). Population structure and ageing. Statistics Explained.

IFR – International Federation of Robotics (2024). World Robotics 2024: Executive Summary—Industrial Robots. (PDF).

IFR – International Federation of Robotics (2024). Record of 4 million robots working in factories worldwide. Press release.

IMF (Misch, F., et al.) (2025). Artificial Intelligence and Productivity in Europe. IMF Working Paper.

IMF (2024). Migration into the EU: Stocktaking of recent developments. Staff Discussion Note.

OECD (2025). Employment Outlook 2025: Setting the Scene.

OECD & European Commission (2024). Health at a Glance: Europe 2024.

OECD & European Commission (2023). Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2023: Settling In. (Overview pages and brochure).

Reuters (2025). AI robots may hold key to nursing Japan's ageing population.

The Guardian (2025). Futurist Adam Dorr on how robots will take our jobs: 'We don't have long to get ready'. Interview.

Web Asha Technologies (2024). The Robot Workforce: Replacing Humans in Industry and Beyond. Blog post.