Borderless Services Trade: Why Tariffs Miss the Target

Input

Modified

Services trade is increasingly borderless and digital Tariffs miss; data rules, licensing, and standards decide access Train for exportable skills and build trust-based regimes to unlock growth

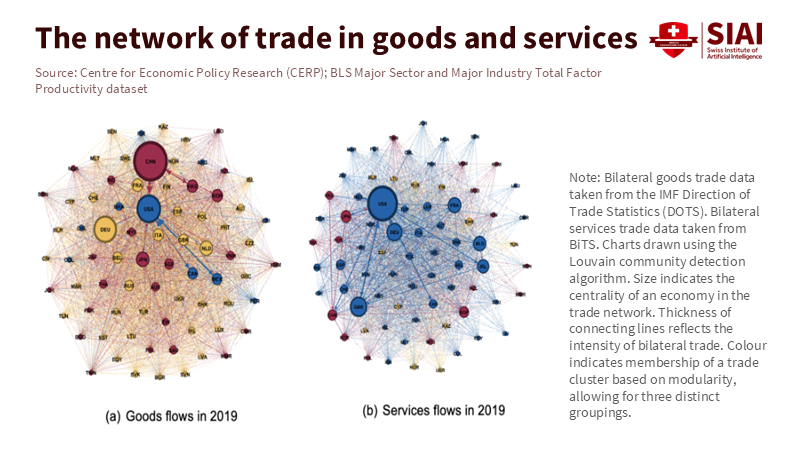

In 2024, the world exported an estimated US$4.64 trillion in services over computer networks, covering everything from cloud engineering to legal review, delivered without a passport or container. Services now represent 27.2% of all global trade by value, which is their highest share in two decades. Distance still matters, but less than before: the estimated “gravity” penalty of miles on services trade has reduced over time, reflecting how work travels through fiber rather than freight. The trend is clear. As borderless services trade grows, the factors that once governed commerce—tariffs, customs lines, ports—lose their grip. This is not a minor change. It is a fundamental shift in how nations earn income and how people sell skills. Policymakers who still reach for tariff schedules are trying to catch the wind with a net. The tools need to change. The outcomes in education and labor markets must change with them.

Reframing trade policy for borderless services trade

The main issue is a mismatch between policy tools and the things they aim to influence. Tariffs direct the flow of goods. They can and do affect sourcing choices—consider the recent increases in electric vehicles and components, which have already raised landed costs and changed compliance incentives in North America's auto rules of origin. But you cannot put a customs seal on a film edit created in Singapore or a model card drafted in Warsaw. Audiovisual streamers face content quotas, not border duties; their catalogs meet local rules on what to show, not tariff lines on how much to pay. This is the essence of borderless services trade: the constraints are political, legal, and digital—not physical. Tariffs work for cars because cars must cross a border; they do not work for movies because movies usually don’t.

The relevant map for services is the WTO’s four modes of supply. Mode 1—cross-border delivery—now covers the fastest-growing portion of services trade. This reflects the daily reality of remote teams spread across time zones. When a consultant in Nairobi finishes a climate-risk model for a client in Dubai, the service crosses the border, not the provider. Policy frictions appear as licensing rules, data-flow limits, or recognition barriers, not as duties at customs. That is why the International Chamber of Commerce argues tariffs are a poor tool for services and why regulators have turned to things like content quotas, data safeguards, and interoperability standards. If we keep treating services like goods, we will continue producing the wrong outcomes and preparing students for the wrong jobs.

What the new data says about borderless services trade

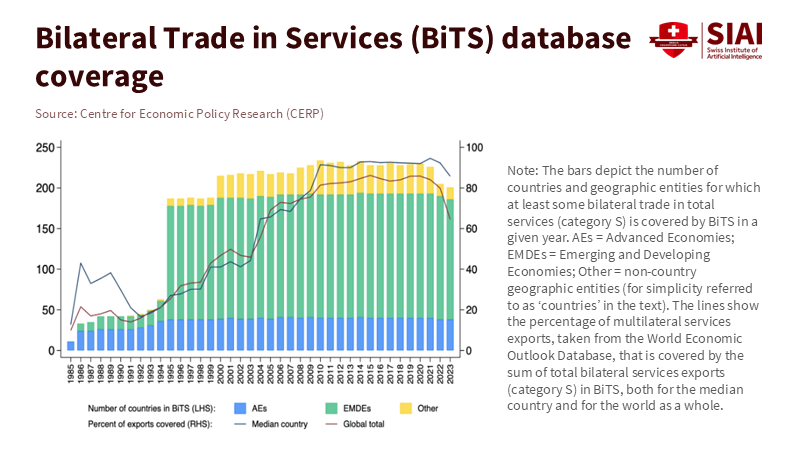

The new Bilateral Trade in Services (BiTS) database tracks flows for up to 245 economies across 12 major categories since 1985. Its first big lesson is about distance: the estimated distance elasticity for overall services trade has moved toward zero over the last two decades, consistent with the practical decline in geography in Mode-1 trade. The second lesson is about composition: a larger share of services is now delivered digitally, shifting the mix toward professional, ICT, and audiovisual segments where the primary constraints are data rules, standards, and recognition—not tariffs. This is why we see rapid growth without corresponding growth in freight. The “pipes” are cables and clouds. The choke points are policies on data use and market entry.

At the same time, digitally delivered services are proliferating in official statistics. In 2024, they reached US$4.64 trillion, marking an 8.3% increase from the previous year. Computer services alone accounted for over a fifth of that total, a share that has increased significantly since 2019. Importantly, this is not just a story of one region or sector. It relies on enterprise spending for software, cybersecurity, and AI-related tasks, as well as households’ consumption of on-demand content. Unlike goods, where a port or a tariff change can reroute ships in a week, the growth of services follows the slower process of building trust and meeting regulatory conditions for data and professional practice. This is why reforming service-sector rules can yield significant benefits.

The OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI) shows why. Across 50 countries and 22 sectors, barriers remain high and, in some cases, are increasing. The usual culprits include licensing tied to nationality, limits on foreign investment, restrictions on data transfers, and vague transparency rules. However, the same metrics suggest that ambitious reforms—especially in upstream sectors like banking, transport, and telecom—can reduce trade costs by 20% to 37% for key services, thereby lowering costs across the entire value chain. In STRI snapshots, air transport and insurance often rank among the most restrictive sectors. At the same time, sound recording and distribution tend to have fewer barriers. These are not just abstract patterns. They directly relate to areas where borderless services trade can expand and where it falters.

Borderless services trade and the future of work

The labor market is already adjusting to this new reality. The World Bank estimates that 154 to 435 million people participate in online gig work globally, representing between 4.4% and 12.5% of the workforce. Demand for gig work rose 41% from 2016 to early 2023. Many assignments are designed to be cross-border: data labeling for a German AI firm completed in Nairobi, vector graphics for a Gulf brand created in Tbilisi, and accounting reconciliation finished overnight from Manila. Payment systems often present the main challenge, not Visa. In borderless services trade, time zones and digital identity matter more than physical distance. The opportunity is significant. The risks regarding social protection and bargaining power are substantial. Education systems that overlook this shift will mis-train a generation.

For educators and administrators, the implications are practical. Programs must focus on exportable services. This means teaching students to be proficient in transferable toolchains, such as Python, Figma, Git, and QuickBooks Online, alongside client-facing skills like scoping, version control, data ethics, and basic contract literacy. It also means assessment methods that reflect real cross-border workflows: asynchronous team projects, hand-offs across time zones, and deliverables that comply with style guides from various jurisdictions. Meanwhile, institutions should facilitate credential recognition with partner schools abroad and align capstone projects with marketable service tasks (e.g., cloud cost optimization or ESG data reconciliation) rather than in-person placements that assume local hiring. When graduates can pitch and deliver a service to any market from a laptop, borderless services trade becomes a career path, not just a slogan.

From tariffs to trust: the new policy toolkit

Policy design needs to shift from tariffs to trust. Start with data. By January 2025, 144 countries had enacted national data-privacy laws, with many now experimenting with localization measures or strict transfer conditions. These rules aim to protect citizens and security, but they also influence market entry for service suppliers. The OECD’s “Data Free Flow with Trust” agenda captures the needed balance: enable cross-border data while ensuring protection and accountability. The WTO’s work on data regulation emphasizes the same point: the main frictions in services are standards, safeguards, and interoperability—not tariffs. Suppose we want to foster growth and resilience. In that case, we should harmonize where possible, recognize limitations where necessary, and be clear about trade-offs when we diverge.

What does that mean in practice? In the audiovisual sector, Europe opted for quotas and prominence rules for European works instead of border taxes on streams. That serves as a model for governing services: shape catalogs and investments to meet cultural goals while keeping the lines open. In professional services, take licensing online, allow supervised remote practice across borders, and establish mutual recognition agreements that keep pace with business needs. In finance and telecom, reduce entry barriers identified by the STRI and publish machine-readable rulebooks so small and medium enterprises can self-serve compliance. Across the board, adopt reference standards for cybersecurity, AI transparency, and audit trails. The benefits are cumulative: every step that lowers regulatory search costs increases the tradable share of services and expands participation in borderless services trade.

What educators and ministries should do next

Education ministries should view borderless services trade as a national export strategy. First, create a services-skills map that connects domestic programs to global task markets by identifying in-demand tasks, the credentials needed to access them, and wage distributions by time zone. Second, support international team projects in final-year courses with micro-grants covering cloud credits, translation, and identity-verification fees. Third, incorporate compliance modules on data transfer, intellectual property, and client confidentiality; these challenges are what graduates will face from day one. Fourth, improve public procurement so universities can buy and sell expert hours across borders, giving students supervised client experience. These measures are small and affordable. They build human capital that can be easily exported.

Labor ministries can support this with portable benefits pilots for cross-border freelancers, based on escrowed contributions from platform invoices. Development banks can help fund regional trust systems—identity, payments, and credential wallets—so smaller providers can meet enterprise onboarding standards. None of this requires tariff action. It calls for regulatory improvements and an education strategy that assumes students will sell services globally. The result is a larger tax base and a more resilient labor market aligned with current value flows.

US$4.64 trillion in digitally delivered services will seem small in a few years. The share of services in world trade continues to rise, and the distance penalty keeps decreasing. Governments can still manage goods with tariffs; that is what ports and customs are designed for. But borderless services trade flows through rules, not docks. If we want to influence it, we need different tools: interoperable data regimes, mutual recognition, open standards, and education that prepares for exportable tasks. Evidence from new services databases, WTO statistics, and the experiences of remote teams points in the same direction. Let us move away from the impulse to tax what we cannot see at the border. Let us focus on governing what actually moves: data, code, and skills. If we do, we will earn more, include more learners and workers in global markets, and make our economies less vulnerable when ships stop or borders close.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

International Chamber of Commerce (2025). Why services can’t realistically be tariffed and shouldn’t be. Paris: ICC.

International Monetary Fund (2025). Bilateral Trade in Services: Insights from a New Database. Washington, DC: IMF Working Paper.

International Organization for Standardization/OECD (2025). Cross-border data flows and trust: Policy approaches in trade and non-trade fora. Paris: OECD.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2024). OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index: Policy Trends up to 2024. Paris: OECD.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2025). Services Trade Restrictiveness Index—2025 update. Paris: OECD.

World Bank (2023). Working Without Borders: The Promise and Peril of Online Gig Work. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Trade Organization (2025). Global Trade Outlook 2025 (and WTO Digitally Delivered Services dataset). Geneva: WTO.

World Trade Organization (2024). World Trade Statistics 2024. Geneva: WTO.

European Commission (2018, updated guidance 2020). Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD): European works quotas and prominence rules. Brussels: European Commission.