Skills Policy for Competition: What Firms' Playbooks Teach Schools

Input

Modified

Firms under competition cut jobs, switch lines, or move tasks offshore Schools need a skills policy for competition: fast, stackable, portable training Fund future-shaping sectors and track outcomes so workers can switch quickly

Three-quarters of all announced greenfield foreign investment since 2022 has gone into what analysts call "future-shaping" industries: clean energy, advanced electronics, biomanufacturing, AI hardware, and their necessary components. This share, measured through May 2025, has increased from about 55% before the pandemic. The direction of capital is clear: competition is shifting quickly. As investment rushes, firms adapt in kind. Some reduce their workforce, others change products or entire industries, and many relocate tasks to sites that are cheaper or more capable. Education systems, on the other hand, progress slowly. Annual adult participation in learning hovers around 40% across the OECD, and a majority of adults report not taking any job-related training in the previous year. In such a changing world, skills policy for competition is not just a slogan. It is the missing framework for schools, colleges, and training agencies that need to respond as rapidly as firms do.

Why competition—not "import competition"—should drive skills policy for competition

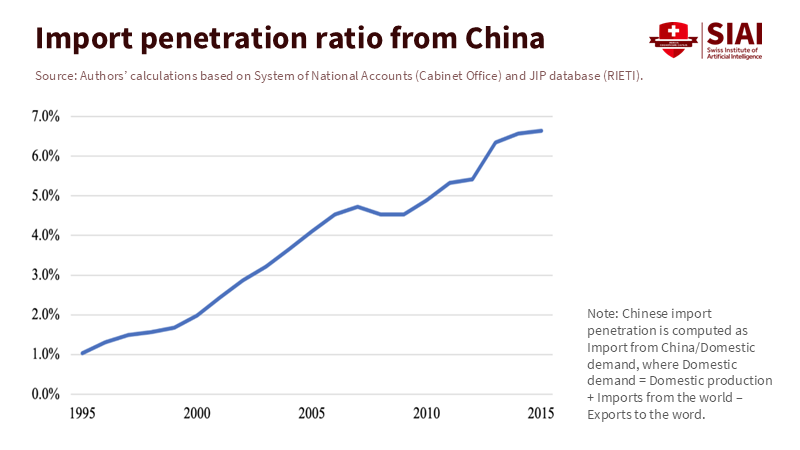

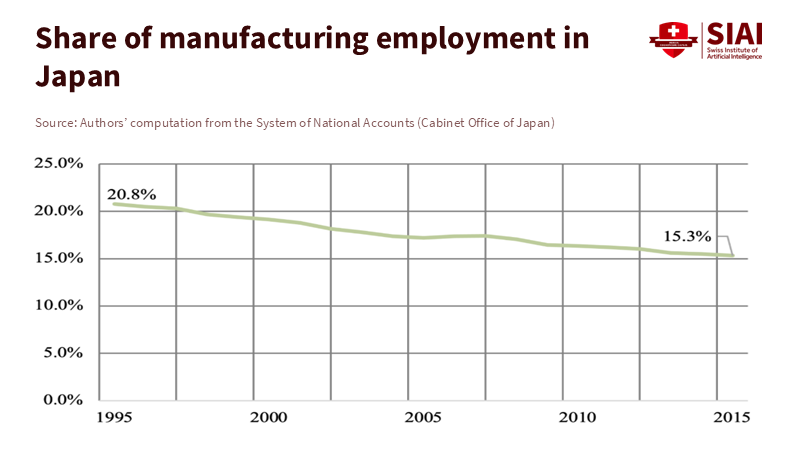

The key question is no longer just how firms react to import competition. It's about how they respond to competition in general. Analysis of large datasets reveals three consistent trends. First, firms downsize when margins tighten. Second, they change what they produce or even the industries they operate in. Third, they reorganize production by offshoring or nearshoring parts of the value chain. Evidence from Japan's manufacturing sector illustrates these trends clearly: in a representative panel, just over half of firms made no changes when faced with increased exposure, while about a third cut jobs, one in ten switched industries, and a smaller group did both—often with a delay between the shock and the switch. Firms that changed products saw fewer minor job losses compared to those that remained static, and offshoring helped ease the impact. The broader lesson is clear: agility is better than inertia. Education systems that prepare workers to switch—and to do so quickly—will better cushion shocks than those that rely on stability.

This is why skills policy for competition is crucial now. The current shifts are not isolated incidents; they are structural. Greenfield Investment is leaning toward technologies that will define the next decade, not the last. Meanwhile, adult learning remains a weak link. Around 40% of adults engage in learning each year across the OECD. Most adults still do not take non-formal, job-related training over the course of 12 months. When competition heightens, systems with low learning throughput will fall behind on speed alone. The mismatch isn't just about how much training occurs; it's also about the type of training. Training must prepare for the same three trends that firms experience: managed downsizing into higher-productivity roles, product and industry switching, and geographic reallocation of tasks. Anything less addresses symptoms rather than causes.

Downsizing, switching, offshoring: what the firm playbook signals for education

Downsizing is tough. It is also common under pressure. The evidence from Japan shows that production workers are usually the first to face cuts when exposure rises, and adjustments to total headcount often come later. Firms that survive do not only cut jobs; they also reorganize. Product switching helps absorb part of the shock, especially when firms can redeploy capital and expertise. Offshoring of intermediate inputs—especially within Asian supply chains—acts as a buffer, buying time and margin. These patterns don't rely on the "import" label attached to the stress; they arise from competition itself. That's the key takeaway for schools and ministries: train for rapid redeployment, not just for entry into a single career.

What skills does the policy for competition require in practice? First, systems must normalize intra-career switching. Credentials should be modular, short, and stackable so that workers can retrain in months, not years. Second, product literacy should complement occupation-specific skills. Workers need to understand supply chains, cost drivers, quality assurance, and digital workflows so they can transition from one product family to another without starting over. Third, geography matters. Offshoring and nearshoring are not just buzzwords; they are evident in trade and investment data. Vietnam's electronics exports reached about US$126.5 billion in 2024, roughly a third of the country's total exports. India's electronics exports increased by about a third year-on-year in FY 2024–25, with iPhone exports alone hitting around US$10 billion in the first half of the current fiscal year. Mexico has become the largest goods supplier to the US, boosted by nearshoring. These shifts influence where jobs and vendor ecosystems are located. Training must keep pace with them.

Institutions shape the choice: Japan and China serve as mirrors

Similar pressures result in different responses because institutions vary. Japan's dual labor market, with a large non-regular segment, has allowed firms to cut labor costs by adjusting contract types and hours. The share of non-regular workers rose for decades, plateaued, and recent analysis shows early signs of decline among women and youth, with some narrowing of pay gaps. Yet dualism remains significant: more than half of employed women still hold non-regular jobs. This setup makes headcount reduction and reassignment manageable within the law. Still, it also concentrates risk among those with weaker ties to training opportunities. Schools and public providers should focus on creating learning paths that reach this group first.

China's situation looks different. Firms under cost and demand pressure have relied heavily on temporary "dispatch" contracts through third-party agencies. While dispatch labor increases flexibility, it also weakens training incentives; both firms and workers treat the match as short-term. Meanwhile, official statistics indicate a labor market under stress, with youth unemployment peaking as it approaches a revised series, and urban joblessness remaining near five percent. In this context, training systems must emphasize portability. If a worker's contract is contingent, their skills should not be. They need credentials recognized across employers and provinces, and public subsidies should support short, verifiable upgrades that facilitate rapid job matching.

These institutional differences are essential for skills policy for competition. Where labor law makes dismissals easy and temporary contracts standard, policy should offset this with stronger rights to training time, transferable credentials, and public co-funding linked to completion. Where protection is stricter, policy should speed the product-switching process by funding rapid curriculum redesign in applied programs, upgrading equipment cycles, and integrating industry projects related to new product lines. In either case, the goal remains the same: shorten the distance between yesterday's tasks and tomorrow's responsibilities.

What should schools and ministries do now

The first step is to align policy timing with that of firms. Businesses adjust every few months, not over decades. Public systems can match that pace by setting annual benchmarks for adult learning that are as noticeable as test scores. One achievable target is to raise adult participation from around 40% to 50% within three years, focusing on job-related, non-formal courses that support transitions. This would bring millions more learners into the pipeline in high-income nations. Transparency will help: publish detailed completion rates, time-to-credential, and wage tracking data so workers can identify the fastest and most rewarding paths.

The second step is to allocate resources where competition is fiercest. The global landscape already highlights key areas. Vietnam's electronics hubs, India's expanding mobile-manufacturing sector, and Mexico's nearshoring surge are attracting new value chains. Ministries should create "switch-tracks" that teach common production languages—quality management, industrial digital tools, fundamental data analysis, supply chain operations—coupled with regional electives connected to these centers. Public agencies can also effectively utilize cross-border resources. When a region lacks instructors or equipment, collaborate with providers where the ecosystem already exists to deliver blended programs locally. This represents offshoring for learning and is a strategic response to capacity gaps.

The third step is to safeguard the time required for learning. With many adults not participating in training each year, barriers—not apathy—are the main hurdle. In the OECD's latest review, 60% of adults reported no job-related, non-formal learning in the past year; a significant number wanted to learn but could not. The solution is straightforward: paid training hours for mid-career workers, portable "learning leave" that remains with the worker rather than the employer, and micro-grants that cover testing costs and transport. When budgets shrink, participation drops; the UK serves as a cautionary tale, with adult learning numbers halved since 2010. As competition increases, funding must keep pace and reach those most likely to be displaced.

The fourth step is to connect the switching to the relevant credentials. Product and industry transitions succeed when workers can quickly prove their skills. This requires simple, verifiable badges with external assessments, not just attendance records. It also necessitates "credit ladders" that seamlessly link micro-credentials to diplomas. Public agencies and employer groups should establish small standard cores in high-demand fields—such as electronics assembly, battery manufacturing, robotics maintenance, and logistics analytics—and discontinue modules that the market no longer requires. Investment data can guide these decisions. With most new foreign direct investment announcements focused on future-shaping sectors, public programs should reflect this trend and update annually to stay aligned with the evolving landscape.

Finally, systems should support the approaches firms actually rely on. If downsizing is inevitable, help workers quickly secure higher-productivity roles—such as quality control, maintenance, programming of industrial equipment, and safety leadership. If product switching is a possibility, provide firms with access to rapid design-for-manufacture modules and line-change simulations in applied colleges. If offshoring or nearshoring is relevant, train local suppliers to meet international certification standards and develop skills that foster effective coordination across production sites. Each of these moves can be taught. None requires a decade. All need clear goals, straightforward funding, and a focus on speed.

Anticipating the pushback

Some may argue that quick transitions could lead to poor-quality courses and credential inflation. This concern is valid if quality checks are lacking. It loses weight when assessments are external, pass rates are public, and outcomes are monitored at the course level. Others might claim that concentrating on "future-shaping" sectors overlooks service jobs. The reality is the opposite. The same skills—process control, data fluency, customer operations, compliance—apply across industries. Switching is not solely about manufacturing; it involves moving people into roles where productivity and pay can increase, including in advanced services. A third worry centers on contract dualism, leading firms to under-invest in training for temporary staff, leaving public systems to cover the costs. The solution is to establish minimum training entitlements for all workers and to co-fund employer training that leads to externally verified credentials. In environments where temporary or non-regular work is the norm, portability is essential.

A final concern is fiscal. However, the alternative is even more costly. When countries cut adult learning budgets, participation declines, and the skills gap widens precisely when competition becomes tougher. Redirecting even a small portion of industrial and investment promotion incentives to fast, verified training could yield higher returns than minor tax adjustments. Firms invest where talent is ready. Skills policy for competition prepares talent swiftly.

Competition has outpaced our education timelines. Capital has shifted to new industries rapidly. Firms have responded by trimming where necessary, switching when possible, and relocating tasks to where they are performed best. The data support this across various contexts, from Japan's detailed firm analyses to the clear trends in Southeast Asia, India, and Mexico. The conclusion for education is both urgent and straightforward. Treat switching as a core outcome, not an exception. Increase adult participation and ensure workers have the time they need to learn. Connect funding to external assessments. Utilize cross-border delivery to fill gaps quickly. Publish outcomes and eliminate modules that the market no longer needs. Suppose we align with the pace of firm decisions. In that case, we will protect workers, boost productivity, and help regions retain industries that remain viable. If not, we will continue preparing for yesterday's competition. The time is now. Skills policy for competition guides us on how to act swiftly.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Acemoglu, D., Autor, D., Dorn, D., Hanson, G., & Price, B. (2016). Import Competition and the Great US Employment Sag of the 2000s. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(S1), S141–S198. (context cited via summary column).

BCG. (2024). The shifting dynamics of nearshoring in Mexico.

China National Bureau of Statistics. (2025, Feb. 28). Press release on employment and unemployment, 2024.

Cedefop. (2025). Skills empower workers in the AI revolution (Policy Brief 9201).

Economic Times/Times of India. (2025, Oct.). India sets iPhone exports record.

Financial Times. (2024, May 27). Funding cuts have halved the number of adult learners in England since 2010.

Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (JILPT). (2024). Non-regular workers after the "equal pay for equal work" policy.

Journal of International Economics, 89(2), 379–392. (context cited via summary column).

Iacovone, L., Rauch, F., & Winters, L. A. (2013). Trade as an engine of creative destruction: Mexican experience with Chinese competition.

India, Ministry of Commerce & Industry (PIB). (2025, Apr. 15). Press release on trade performance and electronics exports FY 2024–25.

India, Press Information Bureau. (2025, Oct.). Exports update.

Lo, V. I. (2024). Labour dispatch in China: Flexibility and security in employment. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources.

McKinsey Global Institute. (2025, Sept.). The FDI shake-up: How foreign direct investment today may shape industry and trade tomorrow.

OECD. (2023). Education at a Glance 2023: To what extent do adults participate in education and training?

OECD. (2024). Measuring progress towards inclusive and sustainable growth in Japan (female non-regular employment).

OECD. (2025). Trends in Adult Learning (chapters on participation and barriers).

OECD. (2024). Addressing demographic headwinds in Japan: A long-term perspective.

Reuters. (2024, Mar. 31). Nearshoring brings a focus on the Mexican peso.

Viet Nam General Statistics Office (via Vietnam Briefing). (2025, May 2). Electronics industry overview, 2024 exports.

VoxEU/CEPR. (2025, Oct. 10). How firms respond to import competition: Labour force reduction, product/industry switching, and offshoring.

World Bank. (2023). Skills Outlook/Skills for Development resources.