Hedging Kabul: How India’s Central Asia Strategy Can Balance China’s Influence

Input

Modified

China is accelerating BRI investment and pushing CPEC into Afghanistan India needs a dual anchor: Russian channels for access; US–EU scale for finance and standards Keep a compliant Chabahar link and build skills-led corridors to retain leverage in Kabul

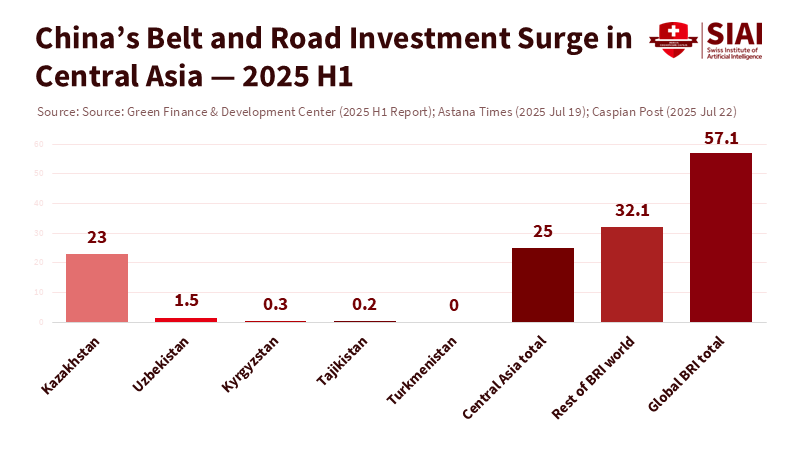

Afghanistan lies at the junction of two corridors that are evolving quickly than New Delhi's policies. In the first half of 2025, China's Belt and Road saw about $57.1 billion in investments and $66.2 billion in construction contracts, marking the busiest half-year since 2013. A significant portion was allocated to Central Asia, where $25 billion was invested, and Kazakhstan alone attracted approximately $23 billion. These are not just signs; they represent real money, metals, and infrastructure pushing west from Xinjiang through the steppe and now reaching Kabul, a direct challenge to India’s Central Asia strategy. China, Pakistan, and Afghanistan have agreed to extend the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) into Afghan territory, intensifying pressure on India’s Central Asia strategy. The United States has also revoked sanctions relief for India's Chabahar lifeline. Meanwhile, Russia is focused on its western front, even as it engages with the Taliban in Moscow. Suppose India wants to exert influence in Kabul and the broader region. In that case, it will need to utilize both American resources and Russian channels, and it must act quickly and on its own terms.

From Corridors to Leverage in India’s Central Asia Strategy

China's approach in Central Asia is straightforward. It moves step by step, combining security discussions with trade, and maintains funding availability. This pattern is evident in 2025. China, Pakistan, and Afghanistan met in Kabul in August to reinforce efforts to include Afghanistan in CPEC. At the same time, Beijing promoted better security cooperation against cross-border violence while fostering trade in agricultural goods and minerals. China has also normalized its diplomatic relations with Kabul faster than others, accepting a Taliban-nominated ambassador by 2023–24. These actions may not amount to full recognition, but they make it easier to launch projects on the ground. In the minerals sector, Chinese companies are consolidating in Kazakhstan, including a $1.2 billion gold acquisition by Zijin. At the same time, think tanks report a strong Chinese interest in copper, lithium, and tungsten across the steppe. The supply line from Xinjiang to Europe now runs through assets that Beijing is financing or acquiring.

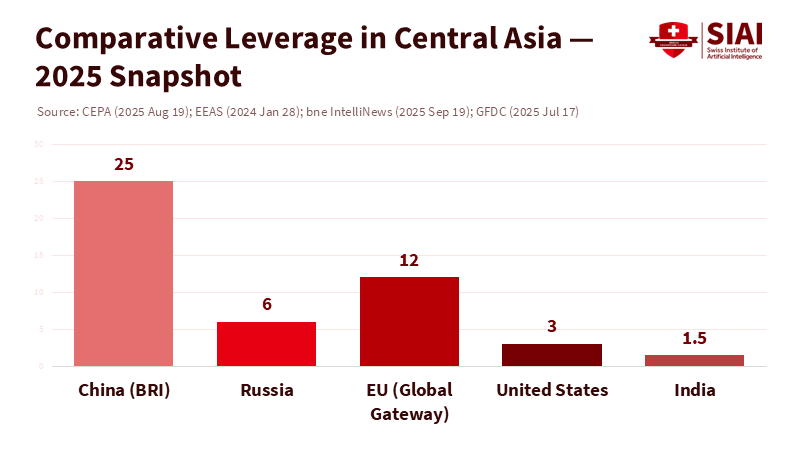

India cannot respond to this surge in financing with mere words. It needs leverage. In Central Asia, this leverage comes from supply chains, insurance, and regulations. The European Union has begun to occupy some of the space not dominated by China with a €12 billion Global Gateway package and a separate €10 billion commitment for the Trans-Caspian corridor. These amounts do not match China's volumes, but they do provide an alternate route for trade and standards. India's challenge is to connect its westward corridors to this funding. This requires quiet collaboration on customs, risk coverage, and scheduling, rather than grand speeches. The real question is whether New Delhi can navigate this. At the same time, its primary overland leverage—Chabahar—faces risks from U.S. sanctions.

A Dual Anchor: Russia and the West in India’s Central Asia Strategy

The rationale for a dual-anchor strategy is practical, not emotional. Russia remains essential for access and conflict management, but it cannot finance the subsequent developments in the region. Moscow is embroiled in a high-stakes war on its western front and must accordingly concentrate its resources and finances. Analysts expect this conflict to continue into 2026, which will keep Russia's attention locked and its finances strained. However, Russia remains active in Central Asia's energy and nuclear sectors, as illustrated by its May 2024 deal to construct Uzbekistan's first nuclear power plant and its ongoing gas diplomacy. India should leverage Russian channels to maintain dialogue in security discussions and transit while acknowledging that the necessary funding and technology will come from other sources.

The United States and the European Union must provide the scale that India needs. Achieving this is challenging this year. Washington has withdrawn its 2018 sanctions exemption for Chabahar, effective September 29, 2025, following months of warnings that the new ten-year India–Iran port agreement could incur penalties. This move puts India's only sanctions-proof land-sea route to Afghanistan and Central Asia at risk. Simultaneously, while the EU's Global Gateway funding is substantial and usable, it will not be implemented. India must transform these Western resources into functioning corridors that transport goods and students. Failing to do so means a Kabul dominated by CPEC's Chinese financing and Pakistani transit by default.

Kabul as the Test Case for India’s Central Asia Strategy

Afghanistan is where India's strategy will be evaluated. China, Pakistan, and Afghanistan have once again committed to extending CPEC into Afghan territory. Beijing pairs this with advancements in mining, agriculture, and security discussions that emphasize non-interference. It has also set a diplomatic pace by accepting a Taliban ambassador and facilitating ministerial talks. Russia has hosted a Taliban delegation in Moscow, positioning itself as a mediator. India opposes the expansion of CPEC on the grounds of sovereignty. However, mere opposition will not keep Kabul in a neutral position. The test lies in whether New Delhi can ensure secure and lawful trade into Afghanistan without the Chabahar exemption while also influencing the rules governing transit and standards.

The immediate outlook is mixed. On one hand, the Taliban canceled a 2023 oil deal with a Chinese firm between June and August 2025, showing that Chinese projects carry risks. On the other hand, Beijing's overall approach—accepting ambassadors, promoting the Belt and Road Initiative, and conducting trilateral meetings—maintains momentum in its favor. The Afghan energy figures are sparse and debated; for this analysis, I rely on reporting from The Diplomat and regional sources, treating volumes as uncertain, rather than as proof of viability. What matters for policy is the direction of travel: diplomatic normalization alongside corridor discussions. This combination sets expectations and attracts providers. India must realign that curve.

Education and human capital are essential to this competition. Corridors are not just for moving containers; they also transport students, technicians, and standards. The EU's Middle Corridor funding aims to shorten transit times; China's Belt and Road Initiative financing is already altering trade routes, creating a demand for logistics and language skills. If India loses access to Kabul's market and training opportunities, it will lose influence over Central Asia's next generation. The solution is not another public seminar. It involves increasing scholarship allocations linked to corridor skills, funding faculty exchanges with Central Asian universities, and offering quick training in customs technology and cold-chain management. These are small steps, but they create a presence that money alone cannot secure.

What India’s Central Asia Strategy Must Deliver Next

First, protect Chabahar. India should establish a clear, transparent humanitarian and education-related corridor that aligns with U.S. policy exceptions and builds on prior allowances. This won't restore the 2018 waiver, but it can reduce sanctions risk for specific items: textbooks, testing kits, vaccines, food for school meals, and medical supplies. This should be paired with third-party logistics agreements that comply with U.S. regulations and regular updates on cargo types and values. This strategy relies on the premise that Washington has revoked the broad waiver but still allows standard humanitarian exceptions; the legal details are essential, and the scope should be negotiated on an individual basis. The goal is to keep the route operational while broader discussions proceed.

Second, build a relationship with Russia without overdependence. Moscow will remain focused on Ukraine until 2026. However, it still maintains influence in Kabul and has ongoing energy ties in Central Asia. India should utilize this opportunity to support a communication channel for conflict management and co-sponsor technical working groups on cross-border trucking safety, customs protocols, and hazardous materials standards—low-profile issues that still significantly impact flow dynamics. The aim should not be high-stakes achievements but steady, practical solutions that keep India engaged while Russia is preoccupied.

Third, expand in partnership with the U.S. and the EU. Link Indian orders for rolling stock, refrigerated transport, and inspection technology to EU Global Gateway initiatives on the Trans-Caspian route. Provide Indian funding and operators where EU money is available, but project development is slow. In Washington, turn the spirit of the India-U.S. collaboration on emerging technologies into tangible corridor-focused tools: a joint insurance fund for Central Asia shipments, shared diligence guidelines for counterparties, and a scholarship initiative for customs and rail technology. These requests are modest yet carry significant signaling value. The aim is to achieve visible results from U.S. and European funds within months, not years.

Lastly, shift Kabul from a symbolic engagement to a systematic effort. Establish a three-year "skills-for-access" agreement with Central Asian governments and Afghan institutions, operating under UN oversight. Focus this effort on logistics, agricultural technology, and health supply chains. Set clear intake targets, monitor progress, and report placement rates. If China offers infrastructure and mining projects, India should provide the skills needed to operate those systems. This is not about charity; it is a strategic move. It is the only way to counter Beijing's gradual expansion with a commitment to human capital that outlasts any single agreement.

The opening statistic—a record half-year for the Belt and Road Initiative with $57.1 billion invested and Central Asia receiving $25 billion—is not just an abstract fact. It is a significant marker. At the same time, Kabul is changing. China, Pakistan, and Afghanistan have promised to integrate it into CPEC. Russia is managing a war while still engaging with Taliban representatives. The United States has eliminated the Chabahar waiver. The message is clear. If India does not act, the region's rules and routes will be established without its input. Over the next year, New Delhi must balance two key anchors simultaneously: Russian channels for access and safety valves, and U.S.-EU resources for finance, insurance, and standards. It must maintain a compliant Chabahar route, connect with Global Gateway projects, and leverage education as a strategic asset. If it succeeds, India will maintain some influence over Kabul. If it fails, it will cede control to others.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera. (2024, May 17). Does India risk U.S. sanctions over Iran’s Chabahar Port deal?

AP News. (2024, May 27). Russia will build Central Asia’s first nuclear power plant in an agreement with Uzbekistan.

AP News. (2025, August 20). Pakistan, China and Afghanistan hold high-level meeting in Kabul to boost cooperation.

AP News. (2025, October 7). Russia hosts Taliban delegation and warns against foreign military presence in Afghanistan.

Arab News. (2025, August 20). Pakistan, China, Afghanistan vow joint fight… extend CPEC to Afghanistan.

Astana Times. (2025, July 19). Central Asia attracts $25 billion, as China’s Belt and Road investment hits half-year record.

Atlantic Council. (2025, August 15). What Russia’s war on Ukraine means for Central Asia.

bne IntelliNews. (2025, September 19). U.S. cancels Chabahar port sanctions exemption in blow to India’s regional strategy.

Caspian Post. (2025, Jul.). Central Asia draws $25 billion… Kazakhstan the largest recipient.

Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA). (2025, August 19). Sino-Russian relations in Central Asia.

CSIS. (2025, Oct.). Russia’s War in Ukraine: The next chapter.

East Asia Forum. (2025, August 23). China builds bridges on uneven ground in Central Asia.

East Asia Forum. (2025, October 7). CPEC’s Afghan push poses a new challenge for India.

EEAS (European External Action Service). (2024, January 28). Global Gateway: €10 billion to invest in the Trans-Caspian corridor.

Green Finance & Development Center. (2025, July 17). BRI Investment Report 2025 H1.

ICWA. (2025, September 2). Pakistan, China and Afghanistan hold trilateral talks in Kabul.

ICWA. (2024, May 21). Chabahar Port Agreement: India’s stride towards Central Asia.

India Today. (2024, May 14). U.S. warns of sanctions after India-Iran Chabahar Port deal.

Reuters. (2023, September 13). China becomes first to name new Afghan ambassador to Kabul.

Reuters. (2025, August 20). China calls for enhancing exchanges, security with Pakistan, Afghanistan.

Reuters. (2025, June 30). Zijin Mining to acquire Kazakh gold mine in $1.2 billion deal.

The Diplomat. (2024, February 1). China welcomes a Taliban ambassador to Beijing.

The Diplomat. (2025, August 1). Taliban end Chinese oil field contract in Afghanistan.

Times of India. (2025, July 24). India slams CPEC expansion to Afghanistan as unacceptable.

Times of India. (2025, September 20). Reviewing implications of U.S. order on Chabahar port.

Times of India. (2025, September 27). U.S. revokes sanctions exemption; what it means for India.