Wage Volatility Is About Who Bears the Risk, Not Just Hourly vs Salary

Input

Modified

Wage volatility is widespread, especially in low-income, hourly education jobs Fixed-wage mandates shift risk to hours and jobs, not remove it Schools should share risk with guaranteed hours, predictability pay, lawful overtime, and work-sharing

U.S. paychecks vary more than most people realize. In about three out of four months, workers take home a different amount than they did in the previous month. The median change is approximately 5%, and in one-quarter of months, the change exceeds 17%. These fluctuations are not just an annoying budget issue; they can disrupt rent payments, debt obligations, and childcare arrangements. They often impact hourly jobs with unstable hours and changing schedules. For educators and support staff, this pattern is familiar: paraprofessionals see their hours reduced when budgets shrink, adjuncts deal with canceled courses, and bus drivers are paid for routes that shift in response to changes in enrollment and attendance. This is what we mean by wage volatility. The real question is not whether volatility occurs—it does—but who faces the risk it causes. When we attempt to eliminate wage volatility through strict rules, we don’t remove risk. We often shift it back onto jobs, hours, or services. The goal in schools and colleges should be smarter risk-sharing, a beacon of hope in the face of wage freezes that backfire.

Wage volatility is about who bears the risk

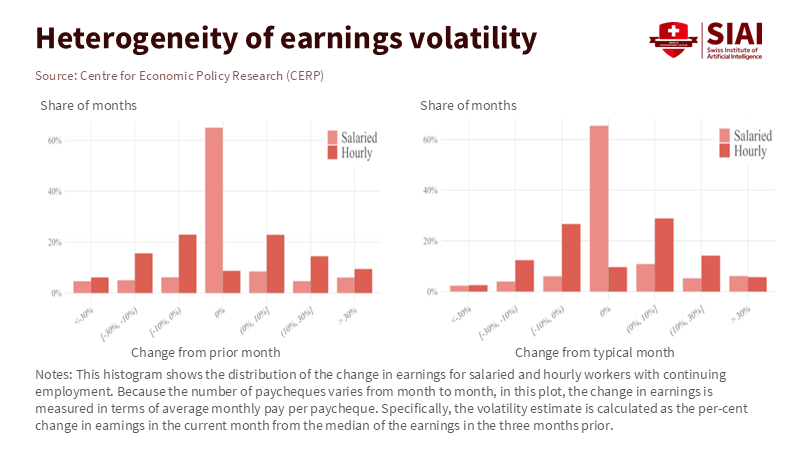

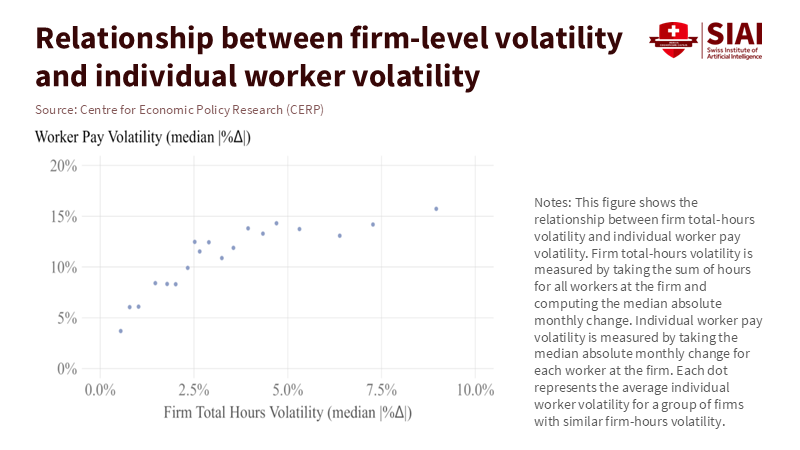

What does wage volatility measure? It tracks the month-to-month changes in earnings that occur even when workers stay employed. Recent evidence from administrative data and bank accounts indicates that these fluctuations are common and unequal: hourly workers experience significantly larger changes than salaried workers, and shifts in firm demand—not just worker preferences—account for a substantial portion of this variation. In the median month, earnings change by 5%, and in one-quarter of months, the change is at least 17%. This volatility affects how people spend and when they pay bills, reducing household stability. These findings are significant in education, as many campus and K–12 roles—such as custodial, cafeteria, transportation, and adjunct instruction—are typically paid on an hourly or per-course basis. Enrollment, calendar changes, and contract timing highly influence their hours. Attempting to suppress these fluctuations with blanket fixed pay rules can turn earnings risk into job risk. The empirical link is clear: when wages cannot change at all, the adjustments typically result in cuts to hours or jobs.

Volatility also impacts lower-income households the most. In 2023, nearly one-third of U.S. households reported that their income varied from month to month; among households earning under $25,000, more than half stated their income was volatile. Workers with unstable income were 3.5 times more likely to struggle with paying bills. They were more likely to report irregular schedules imposed by employers. These issues are not merely lifestyle choices; they reflect the functioning of low-wage labor markets. In education, this reality appears when a paraprofessional loses hours due to shifts in a student’s individualized services or when an adjunct’s second section is canceled just days before the term begins. The data doesn’t suggest that hourly work is “bad” while salary is “good”; instead, it shows that volatility concentrates where bargaining power and control over schedules are weakest. Any solution must begin there.

Hourly vs salary: the fair comparison educators deserve

A fair comparison acknowledges both the protections and the trade-offs. Hourly workers under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) must receive overtime pay of at least time-and-a-half for hours worked over 40 in a week. This offers genuine protection against unpaid overtime and provides a means to earn more during busy periods. On the other hand, salaried “exempt” roles do not receive overtime pay, as long as they meet specific duties and salary thresholds (typically at least $684 per week under current federal rules), which can shift the risk back to employees during periods of heavy workload. In many educational roles, whether a position is hourly or salaried depends on the duties and classification, not personal preference. Many support staff are hourly, while administrators and most full-time faculty are salaried. The aim is not to favor one status over another but to highlight who bears the burden when demand fluctuates.

Benefits coverage varies by job type and the number of hours worked per week. By 2025, employer benefits will account for approximately 30% of compensation costs across the economy, but access remains far from universal. Lower-wage and part-time roles—typical in school support services—have systematically less access to retirement, paid leave, and health coverage compared to higher-wage full-time positions. These disparities help explain why hourly school workers can suffer more from volatility, even when their base pay seems reasonable. In K–12, nearly a third of support professionals earn under $25,000 a year, and earnings for school clerical, bus, and food service roles lag behind the median U.S. worker by wide margins. Additionally, part-time and adjunct faculty often get paid per course with limited benefits, which can increase volatility when classes are added or dropped. Salary offers predictability, while hourly work provides overtime rights and pay for actual hours worked; each type of contract suits different risk profiles.

The market context is essential, too. In 2024, 80.3 million Americans, about 55.6% of wage and salary workers, were paid hourly. For these workers, predictable scheduling rules can help stabilize pay without banning overtime or variability. Studies on “fair workweek” laws suggest they improve advance scheduling notice and reduce last-minute adjustments. However, they also impose absolute limits on staffing flexibility. The best results come from carefully designed plans that allow for exceptions in response to genuine demand shocks, such as unexpected increases or decreases in student enrollment, and explicit pay formulas, enabling employers to adjust shifts at short notice. Schools and colleges already operate on rigid calendars; they can adopt versions of these rules to reduce volatility for hourly staff while allowing program leaders to adjust when issues such as broken buses or enrollment changes arise.

Risk-sharing beats wage freezes: a plan for schools

Districts and colleges need to share a common understanding to address wage volatility. Start by tracking the month-to-month changes in earnings for each job family, such as transportation, food service, paraprofessionals, facilities, and adjuncts. Use payroll data to create a straightforward volatility index. Report the median absolute changes in pay at the job and unit level. When leaders see, for example, that paraprofessional earnings fluctuate by 15 to 20% with IEP schedules, they can target interventions instead of using a one-size-fits-all approach. This understanding is key to addressing wage volatility effectively.

Income stability improves when rules create a safety net while allowing for smart flexibility. Replace rigid “fixed wage” ideas with guaranteed-hours baselines, along with clear extra pay for short-notice changes, call-ins, and peak-period coverage. Pair this with predictable scheduling norms, such as giving two weeks' notice whenever possible, and include written exceptions for genuine emergencies. This combination reduces wage volatility while keeping buses, cafeterias, and classrooms staffed in the event of unexpected situations.

Layoffs should be a last resort, not an automatic response. Work-sharing programs enable employers to reduce hours across the board, while unemployment insurance covers part of the lost wages. In cases of lower revenues in cafeterias or transportation, work-sharing helps share the burden fairly, limits job separations, and reduces wage volatility more effectively than cutting a few positions entirely.

Timing is almost as important as the total pay. Paycheck smoothing options, such as fee-free same-day pay, biweekly pay schedules that align with actual work, and strict limits on earned-wage access, prevent volatility from leading to debt. If third-party tools are permitted, require them to have no mandatory fees, clear disclosures, and restrictions against debt-like cycling. The goal is to stabilize income flows, not add to financial stress.

Compensation ladders can help protect against financial shocks instead of hiding them. Create base guarantees with clear premium ranges related to job duties, volatility, and performance. Add “stability differentials” for roles that show significant earnings swings. Where collective bargaining is intense, make these ranges official; where it is weak, publicly share the formulas that underpin them. This approach reduces wage volatility without shifting risk to employee hours or headcount.

The school plan for managing wage volatility includes practical tools that protect jobs and services

Benefits can help stabilize income for workers facing the most volatility. Expand paid sick time and retirement contributions to employees working 20 hours per week. Smooth out health insurance deductions for 9- or 10-month employees across a whole year to prevent income drops in summer. For adjuncts, offer pay-per-course stipends in even biweekly payments and require fees for cancellations made close to the start dates. The total spending can remain the same while wage volatility decreases.

Hourly work has real benefits, and schools should keep it. Overtime rights compensate for genuine surges, such as during testing weeks, graduations, or summer programs, allowing staff to earn more when demand rises. Maintain this advantage with a guaranteed minimum and clear extra pay, and do not misclassify roles as “exempt” to achieve predictability. Correct classifications safeguard overtime rights and prevent shifting hidden risks back to employees.

Operational improvements should be measured alongside pay stability. When bus driver volatility decreases, the number of on-time arrivals increases. When paraprofessional schedules are steady, IEP support becomes more reliable. When adjunct pay remains consistent, the chaos of drop-add situations eases for first-generation students. Share these metrics, along with the volatility index, so boards can recognize that reducing wage volatility is essential for delivering dependable services.

Trade-offs require transparency. Being hourly is not inherently worse than being salaried, and a salary does not automatically provide protection. Hourly roles ensure pay for actual work and overtime; salaried positions offer predictability but can obscure spikes in workload. The policy question concerns who bears different risks, when, and what compensation is involved. In education, that answer involves guaranteeing minimum wages and extra pay for hourly workers, as well as time-limited stipends for salaried staff during known peak periods.

Good ideas can fade without proper institutional memory. Include the volatility index, guaranteed-hours standards, premium calculations, and evaluation results in board policies and union contracts. Reaffirm them every year. When budgets tighten, initiate work-sharing before resorting to layoffs, pay predictability premiums for late changes, and protect surge pay. Over time, wage volatility can stabilize within a manageable range—making it workable for families and staff while allowing schools to adjust to real challenges.

Wage volatility is not a moral failing of hourly work. It is a part of how labor demand and schedules shift in the real world. Recent evidence makes the central fact hard to ignore: paychecks change in most months, especially for hourly workers in lower-income jobs, and much of that change comes from companies’ needs, not workers’ choices. Suppose we try to eliminate volatility by enforcing fixed wages. In that case, we shift the risk elsewhere—onto hours, hiring, or services. Education systems cannot handle that. They need reliable buses, clean buildings, staffed cafeterias, and stable classrooms. The right approach is risk-sharing: guaranteed hours, transparent and fair pay for last-minute changes, lawful overtime, work-sharing before layoffs, and fee-free smoothing of pay timing. When used effectively, these tools preserve the benefits of hourly work, maintain salary predictability, and balance the impact of disruptions with institutions that can handle them, rather than placing it on the most vulnerable workers. This is how we make wage volatility manageable without losing jobs or quality.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

American Economic Association (2024). Wage Rigidity and Employment Outcomes: Evidence from Administrative Data.

American Federation of Teachers/Inside Higher Ed (2024). Adjunct Faculty Compensation Models (AAUP data summary).

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025a). Employer Costs for Employee Compensation—June 2025.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025b). Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers, 2024 (hourly share).

Brookings Institution (Bauer, East, & Howard, 2025). Low-income workers experience—by far—the most earnings and work hours instability.

Center for Economic Policy Research / VoxEU (Ganong, Noel, Patterson, Vavra, & Weinberg, 2025). U.S. workers experience large month-to-month fluctuations in pay.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2024). Proposed interpretive rule on paycheck advance / earned-wage products.

JPMorgan Chase Institute (2025). The hidden volatility of American workers’ paychecks.

National Education Association (2025). Educator Pay Data 2025; School support staff earnings.

Upjohn Institute (Pickens, 2025). Effects of Fair Workweek Laws on Labor Market Outcomes.

U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division (n.d.). FLSA Fact Sheet #17A: Exemption for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees; Fact Sheet #17G: Salary Basis Requirement.

Washington State ESD/University of Washington (Jardim et al., 2022). Minimum-wage increases and low-wage employment: Evidence from Seattle.

Associated Press (2024). These apps allow workers to get paid between paychecks. Experts say there are steep costs (earned-wage access).

City & State Fair-Workweek Overviews (2023–2025). Predictive scheduling summaries and guides.