Hot Memory, Cold Politics: How the Emotional Intensity of Historical Memory in Japan, China, and South Korea Affects Political Dynamics

Input

Modified

Media-driven memory politics outpaces classroom teaching in East Asia Cross-border, source-based history lessons can counter quick nationalist swings Schools must prime students before flashpoints to cool future conflicts

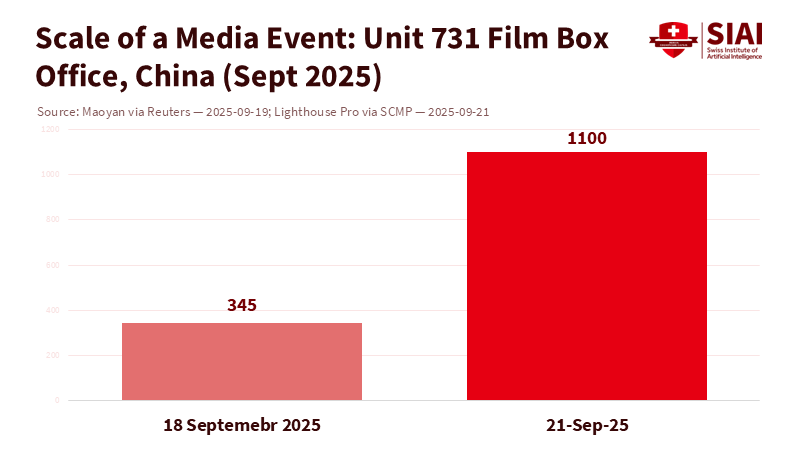

The most-watched history lesson in East Asia this month took place at the box office, not in a classroom. A new Chinese film about Japan’s wartime Unit 731 set a first-day record for war films in China, earning over 345 million yuan. That amount reflects a massive tutorial, with millions of tickets sold and millions of viewers engaging with a single narrative of the past. The same week, air-raid sirens marked the anniversary of Japan’s 1931 invasion, combining ritual, remembrance, and cinema into a single national rhythm. Politics follows that rhythm. In Tokyo, cabinet ministers and right-wing lawmakers visited Yasukuni on August 15, garnering praise at home and protests abroad. These actions are not isolated or trendy viewings. They demonstrate how memory is organized, monetized, and weaponized on a large scale in 2025. Suppose we want a more stable Northeast Asia and better civic education. In that case, we need to ask not whether Japan has reckoned enough but whether education policy in Japan, China, and South Korea can compete with the political economy of hot memory through slow, shared learning.

The politics of memory has become a media economy

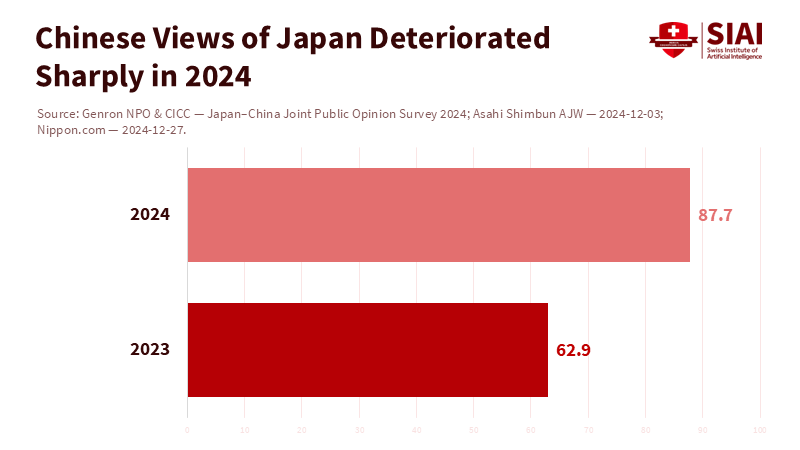

We often act as if historical grievances are fixed. In reality, they respond to the interplay between demand and supply. In China, public opinion about Japan is strongly negative. In 2024, 87.7 percent of Chinese respondents reported a “bad impression” of Japan, one of the highest figures since 2005. This negative view isn't caused solely by textbooks. It rises and falls with media events, diplomatic issues, and well-timed releases that turn memory into momentum. Take the new Unit 731 blockbuster. With an average ticket price of 45-50 yuan, the first day’s gross suggests roughly seven to eight million viewers—equivalent to the population of Hong Kong—experiencing a vivid, curated account of atrocities. When a prime minister suggests in parliament that evidence about Unit 731 has been “lost with history,” the narrative gap only widens, and the market fills it. This cycle favors simple moral calculations over complex, comparative learning.

Japan’s domestic politics reflect this emotional economy. Visits to Yasukuni carry specific meanings. On the 80th anniversary of Japan’s World War II defeat this August, ministers and ambitious leaders paid their respects, joined by a rising nationalist party. This choreography was precise for both supporters and opponents. Beijing condemned the visits, while Seoul expressed disappointment and regret. The result is predictable: every action taken to solidify support at home limits trust abroad. Education policy cannot ignore this reality. It must acknowledge that students live in media ecosystems that reward outrage, oversimplify blame, and turn the past into content for profit. The challenge is not to mute memory but to make learning more engaging than spectacle.

When textbooks lose students to screens

There is good news. Korean views of Japan improved in 2023-2024 on several measures. A record 42 percent of South Koreans reported a favorable view of Japan in one poll. However, the improvement is fragile. In mid-2025, only about a quarter of respondents in both countries said their bilateral ties were “going well.” This volatility speaks to education. If classroom narratives were compelling, we would expect more stability. Instead, sentiment shifts in response to diplomatic headlines, viral clips, and foreign policy controversies. The curriculum is no longer the main channel. Education ministries compete with media platforms and need new tools.

Previous initiatives show that co-producing history is possible but fragile. Japan and South Korea established a joint history research committee in 2001, followed by a similar commission between Japan and China in 2006. Scholars made progress on technical issues and published reports. However, these projects struggled to reach classrooms and popular culture, where simplified narratives thrive. The lesson is not that joint scholarship fails; it is that scholarship without effective distribution loses to cinema and social media. To create a learning scale, we need distribution models that align with today's attention economy. This means creating curricular additions that circulate like media, not simply reports that remain on ministry websites or university presses.

The film wave serves as a wake-up call for educators. When millions view a single depiction of Nanjing or Unit 731 over a weekend, any counter-narrative introduced months later in a classroom comes too late and feels too cold. We should not ask students to “balance” propaganda with abstract ideas. Instead, we should teach them how to interpret images, which archives were used, what was left out, and what leading historians say about disputed facts. This is media literacy focused on war memory, not a generic unit on “critical thinking.” It can be taught without moral relativism. Students can hold two truths at once: that Imperial Japan committed severe crimes and that today’s citizens, including young Japanese, do not inherit guilt, but do hold responsibilities. This distinction represents civic education, not appeasement. It shifts the conversation from identity to agency.

Building a History Education for the Future

The policy stakes extend beyond simple bilateral etiquette. East Asia’s security framework relies on public support for deeper cooperation among Japan, South Korea, and the United States. That support becomes harder to achieve when every commemoration turns into a referendum on accountability. We can lower the temperature without lowering standards. The way forward includes concrete educational reforms that meet students where they are and make empathy rigorous and transparent. Start with a cross-border “History in Sources” module co-assigned by teachers in all three countries. Build it around digitized primary sources—such as diaries, court transcripts, and photographs—curated in collaboration with national archives. Pair each set with brief explainers recorded by historians from each country, available in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. Release the materials on a fixed schedule, anticipating key dates such as August 15 and September 18, to ensure classrooms are ready before political tensions escalate. This is not a performance of reconciliation; it is curriculum design that respects the public square's rhythm.

Second, establish a teacher-exchange residency that pairs secondary-school instructors across the three countries for one semester. Teachers would co-plan two units: one on a low-controversy topic, such as migration in the 1910s, and one on a high-controversy topic, like forced labor or military sexual slavery. The aim is not to find a single “shared truth,” but to develop a shared method for handling contested evidence, identifying gaps, and distinguishing facts from those still debated. We know there is demand. In 2024, negative sentiment in China toward Japan sharply increased, while Japanese views of South Korea improved in 2023-2024 before declining again regarding bilateral relations. These shifts correlate with signals students receive outside the classroom. Provide teachers with materials that translate these signals into teachable questions rather than divisive triggers.

Third, modernize assessment. Replace one-off essay prompts with multimedia portfolios. Ask students to annotate a movie clip using citations from primary and secondary sources. Require them to reconstruct a single event—from the Shanghai outbreak of plague to a specific date on a street in Nanjing—from three different perspectives. Evaluate them based on sourcing rather than emotion. In Japan, this could include explicit instruction on what a Yasukuni visit signifies abroad and why it evokes fear rather than merely grief. In South Korea and China, this could pair with modules about post-war Japanese pacifism and democratic movements, showcasing how some Japanese groups challenged conservative narratives. The goal is to ensure that each system teaches not only its own pain but also the dissenters' perspectives in the others.

A regional education fix, not another apology

All of this may seem naïve. Critics may argue that the curriculum cannot keep pace with politics, that cinema will always prevail, and that apologies will never be sufficient. The first view misunderstands the landscape. The curriculum has lost ground because it has not addressed memory as a distribution issue. When learning is crafted to circulate like media, it gains influence. The second view underestimates students’ capacities. Young people are skilled at interpreting images; they can learn to read them in a historical context. The third view highlights the importance of maintaining consistent messages. Citizens across the region do not want a rehearsed statement; they seek ongoing actions from leaders, not just words. Even in years with improved relations, perceptions change when symbols reopen wounds. A credible educational solution would make these shifts less frequent by fostering lasting habits of cross-referencing evidence and viewing people across borders as learners, rather than as avatars.

Here is a practical plan for ministries and administrators. Allocate funds for an East Asia “shared sources” repository with synchronized release dates, rather than random uploads. Negotiate rights for film clip use in classrooms so teachers can present the viral content rather than sanitized alternatives. Connect teacher promotions to demonstrated skills in evidence-based instruction on complex topics. Support exchanges not just among historians, but also among curriculum designers and media creators. Recognize school networks that share open lesson plans others can use. For universities, establish a tri-national online course that offers credit, enabling undergraduates to practice those skills on a large scale. In teacher education programs, make a short module on “memory and media economics” compulsory. Educators should grasp why a film can reach more viewers in 48 hours than a textbook does in five years.

Political leaders also need to refrain from using memory as a means to manipulate others. Leaders in Tokyo understand that visits to Yasukuni lead to diplomatic strain. Those in Beijing and Seoul know that inciting anti-Japanese feelings is easy politics. The results are stark: sharp, media-driven fluctuations in sentiment that hinder meaningful cooperation on issues such as climate change, science, and security. Progress can happen—record-high favorable views one year and improved perceptions of ties the next—but they remain fragile without a civic base that learns to handle grief and complexity together. An education strategy that teaches students to engage with sources rather than slogans is the most realistic approach to building that base.

The goal isn’t to forget atrocities. It is time to move forward with understanding. This represents both a moral and a practical stance. Policymakers often ask how to reduce the political benefits of revisiting “glorious moments” or stirring anger over imperial crimes. The solution lies in lowering the demand for sensationalism by flooding the system with credible, engaging learning that students find worthwhile. Envision if the next big war film triggered a week-long regional lesson, complete with open archives, coordinated teacher guides, and student-generated annotations shared across borders. Imagine if August 15 and September 18 became not just days for rituals and speeches, but also days for structured, comparative learning. This is not a fantasy; it is a policy choice.

We began with a statistic: 345 million yuan in one day, and millions of viewers were taught to feel the past in a particular way. We can continue to lament that politics will always dominate these narratives, or we can create an education system that understands them and performs better. Japan will continue to grapple with how it memorializes its past, just as China and South Korea will continue to highlight their own stories. None of this calls for another futile debate over who apologized when. It requires a commitment to teach evidence with the same energy that politics uses to teach identity. This is a task for education ministries, teacher colleges, and school leaders today. By funding shared sources, preparing classrooms ahead of political flashpoints, and rewarding instruction that treats students as budding historians, we can ease the politics of memory without softening its lessons. The future of the region’s security—and the civic well-being of our students—depends on it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asahi Shimbun (2025). “South Korea criticises Japanese officials’ visit to Tokyo war shrine.” August 16, 2025.

Asahi Shimbun (2024). “South Koreans with ‘favorable’ view of Japan at record 42%.” October 16, 2024.

East Asia Forum (2025). Nishimura, T. & Kotler, M. “Japan’s reckoning with the past remains a work in progress.” September 24, 2025.

Genron NPO (2024). “What the Japan–China Joint Public Opinion Poll 2024 revealed.” December 2, 2024. (Summary and data cited via Nippon.com.)

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan & PRC (2011). Japan–China Joint History Research Report. (Overview of joint historical research process and outcomes.)

National Association of Korean History / Northeast Asian History Foundation (n.d.). “Why Korea–Japan Joint Historical Research?” (Background on the 2001–2010 project.)

Reuters (2025a). “Japan minister joins crowds at contentious shrine to mark 80 years since World War Two defeat.” August 15, 2025.

Reuters (2025b). Chu, M. “Chinese film on ‘evil’ WW2 germ warfare unit risks adding fuel to Japanese tensions.” September 20, 2025. (Includes first-day box-office and PM comment on Unit 731.)

SCMP (2025a). “China marks grim anniversary tied to Japan’s aggression with air-raid sirens, film debut.” September 18, 2025.

SCMP (2025b). “Hit Chinese film about Japanese war crimes highlights ‘forgotten history’.” August 10, 2025.