If You Can't Insure It, You Can't Permit It

Published

Modified

AVs must pass an insurance test—no policy, no deployment Permits should hinge on corridor-specific coverage and quarterly audited claims data Keep driver-assist and driverless distinct; if it’s not insurable at market rates, it’s not permissible

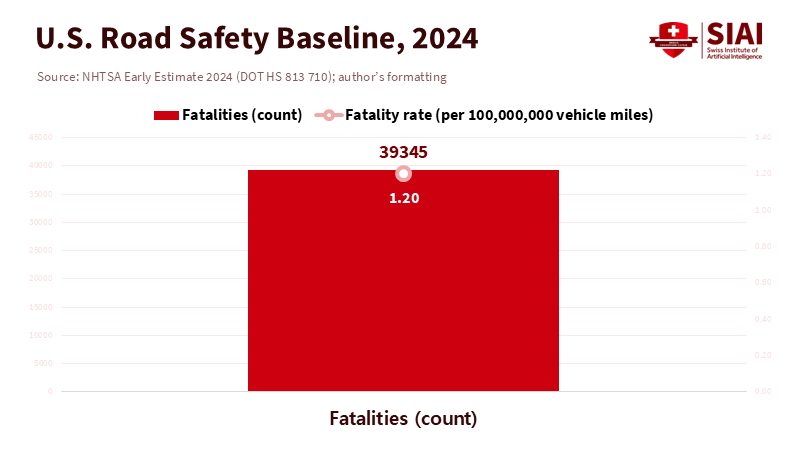

The most critical number in this debate is not the number of lidar beams or neural-network parameters; it's 39,345. This is the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's early estimate of U.S. road deaths in 2024. While this number has decreased from 2023, it still represents about 1.20 fatalities for every 100 million vehicle miles traveled. Even in a so-called "good" year, this is an unacceptable baseline risk that we address every day through insurance. If self-driving technology is truly safer, it should be easy to prove this in a domain that relies on quantifiable risk: insurance. If an actuary cannot price your system without public support or legal protection, it doesn't deserve to operate at scale. Insurability is not a minor detail in regulation; it is the market's test of credibility. If we can't ensure it, we shouldn't let it go into operation.

From Liability Theory to Priceable Risk

To make that test concrete, we need to start with liability assignments that can actually be priced. The United Kingdom has progressed the most, with Parliament establishing a scheme that puts primary responsibility on motor insurers while an automated system is in use. This allows insurers to seek recovery from the manufacturer as needed. This clarity, set out in the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act and updated through the Automated Vehicles Act 2024, turns a philosophical debate into a contract that the market can handle. If a crash happens while the system is in "automated mode," the policy responds. If a software defect is to blame, the insurer can seek compensation from the developer. This is a key regulatory change because it outlines the losses for which insurers are accountable and under what conditions. In the United States, we, by contrast, have an inconsistent mix of tort laws and state-level pilot regulations; federal safety reporting exists, but liability clarity is lacking. A reasonable standard is straightforward: no large-scale deployment without a policy that a licensed insurer is willing to underwrite at market rates for the specific automated use-cases, such as a driverless robotaxi operating within a designated area or highway-only automation with a human supervisor.

Underwriters do not price hopes or ambitions; they price exposure. They care about a company's loss history, not its confidence. A growing set of data sources can help clarify the situation. California's disengagement and mileage datasets, although imperfect, still provide valuable insight into operational reliability. NHTSA's Standing General Order requires the timely reporting of crashes involving advanced driver assistance (Level 2) and automated driving systems (Levels 3-5), finally creating a minimum standard for evidence. None of these datasets is flawless, but they are vital for the credibility calculations actuaries need to determine whether past performance can inform future loss ratios. The aim is not to achieve absolute certainty; it is to establish insurability with precise confidence intervals and identifiable exclusions.

The Current Signal from Insurance Data Is Mixed

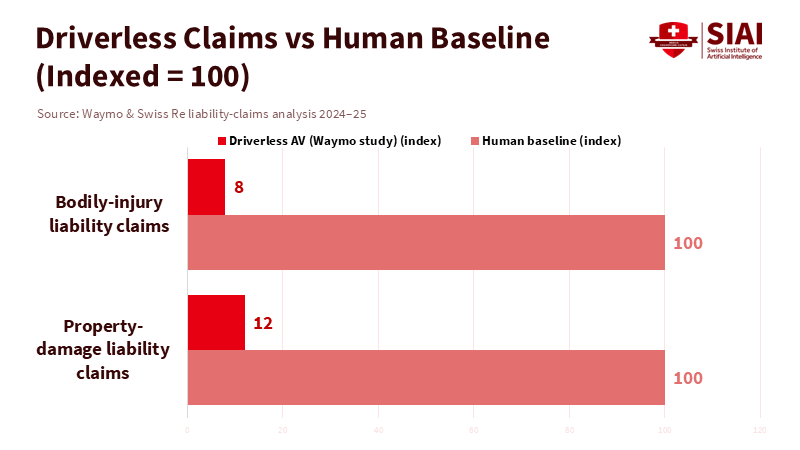

If we look at where insurers focus—on claims, not social media—the signals point in two directions. On the bright side, Swiss Re's analysis of 25.3 million fully driverless miles operated by Waymo in Phoenix, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Austin reveals significant reductions in liability claims compared to baselines from over 200 billion human-driven miles: about an 88% drop in property damage claims and a 92% drop in bodily injury claims. Nine property-damage claims and two bodily-injury claims over that exposure are a small sample. Still, it represents the type of evidence that can shift underwriters from "maybe" to "what premium reflects that improvement?" This isn't just a marketing claim; substantial data from a major reinsurer support it. The findings may not apply to every technology stack or city, but they demonstrate that risk can be measured and priced when operations are well defined.

However, the negative signals are equally important. During the same time frame, the most widely recognized "self-driving" brand in the U.S. rebranded its offering to "Full Self-Driving (Supervised)," highlighting that a human must remain accountable. Regulators have consistently pursued investigations and scrutinized recalls, with official reports linking the company's Level 2 system to several fatal crashes. This does not end the conversation—Level 2 is fundamentally different from driverless Level 4—but it stresses that not all automation should be treated the same. A supervised assist feature relying on human fallback is not a proof of autonomy for insurance; it is a traditional auto policy that comes with new risks of misuse and defects. The firm's labeling change is an acknowledgment of this reality and serves as a reminder that insurability hinges on the mode and operational design domain, not just branding.

Method matters. Claims-frequency comparisons must account for exposure and be matched based on context: time of day, weather, road type, crash reporting standards, and average annual miles per vehicle. The Waymo-Swiss Re study attempts to address this by benchmarking against both general and "latest-generation" human-driver standards. Still, even then, a reinsurer will adjust the improvement until the confidence intervals tighten. Meanwhile, NHTSA's 2024 fatality rate serves as a reminder that the human baseline is not static. If human risk is declining—1.20 fatalities per 100 million miles in 2024, with early 2025 trends looking better—then the standard for an AV system to prove superiority rises. This is precisely why a market standard should be adaptable: a moving benchmark that insurers can and must adjust as the human baseline changes.

A Practical Insurability Standard for AV Pilots

So what does an "insurance-first" standard look like in practice? It starts with specificity. Policies must be clearly defined for a declared operational design domain (ODD): streets and times, weather conditions, fallback behavior, and whether a paid safety operator is present. Underwriters should provide an expected claims frequency and severity range for that ODD, along with a stated limit and retention, and confirm reinsurance support. An acceptable entry requirement could involve an A-rated insurer ready to issue primary coverage at typical market margins; transferring at least 30% of gross risk to an A-rated reinsurer; and implementing a parametric stop-loss that activates at predefined frequency or severity thresholds based on a human-driver baseline. The policy should consider software updates as endorsements that change risk, necessitating new rates when the technology stack undergoes significant changes. This is not excessive regulation; it ensures capital believes in the safety case enough to price it accurately.

The second pillar is data sharing that justifies those prices. The baseline is what California and NHTSA already require: reports on disengagements, miles driven, and crashes with standardized information. The next step is obtaining insurer-grade exposure and loss data: insured miles segmented by ODD, near-miss indicators (hard braking and significant lateral movement beyond set thresholds), third-party claims with injury coding, and repair cost distributions by component. Regulators should mandate that, as a condition for renewing permits, operators publish anonymized quarterly exposure and claims tables verified by an independent party. This framework won't make immature systems safe but will make unsafe systems costly, while rewarding mature systems with lower costs. That is the right incentive.

To align permitting with market signals, cities or states should approve driverless services only when insurers are willing to provide coverage without extra legal protections beyond standard measures. Public authorities can create "risk corridors" for pilots, co-funded with operators committed to transparency. At the same time, the UK model, where insurers act as first payers, offers a valuable framework for the U.S.

Concerns about insurers being gatekeepers are misdirected, as they already play this role due to the nature of capital. Although early-stage technologies may lack loss history, specific thresholds for each corridor can provide clarity. Insurance markets may shift, but stable data sharing and pilot testing can maintain standards without relaxing regulations.

Education should focus on practical risk engineering over theoretical ethics, fostering skills in areas like safety-case development and actuarial theory. Policymakers should budget for independent data audits as essential to AV permitting, promoting better measurement as a vital subsidy.Messaging must differentiate between levels of automation. Levels 2 and 3 are driver-assistance tools covered by traditional policies, while Level 4 requires distinct insurance based on specific usage rules.

By 2024, improvements in driverless operations are expected to prompt a shift towards formal testing, with the expectation that by 2026, all jurisdictions will mandate clearly priced primary policies alongside reinsurance for each operational design domain (ODD). This approach acknowledges where autonomy is safer while maintaining regulatory standards.The insurability test is not about reducing regulation or providing moral exemptions; it ensures accountability. Cities may subsidize premiums for data collection, but with strict limits. Ethical considerations around mobility and urban planning remain crucial as deployment progresses.

The starting point and the endpoint are the same number. Thirty-nine thousand three hundred forty-five is the floor we are trying to break. Suppose autonomy can lower that number in real corridors, in real weather, with real claims. In that case, insurers will rush to get involved, and regulators will see a strong market signal that allows for expansion without any drama. If autonomy cannot be insured without public backing, then we have our answer for now: we need more engineering, more measurement, and stricter ODDs until the actuarial math changes. The only rule we need to state—and the one we should enforce strictly—is simple: if you can't insure it, you can't allow it. That rule aligns incentives, protects the public, and gives the technology a fair chance to prove itself where it matters—on the balance sheet of risk.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Association of British Insurers (2024). Insurer requirements for automated vehicles. Retrieved from abi.org.uk (PDF).

Brookings Institution (2025, August 8). Setting the standard of liability for self-driving cars. Retrieved from brookings.edu.

California DMV (2023). Autonomous vehicle disengagement and mileage reports. Retrieved from dmv.ca.gov.

European Commission (2025, March 18). EU road fatalities drop by 3% in 2024, but progress remains slow. Retrieved from transport.ec.europa.eu.

MarketWatch Guides (2025). How will self-driving cars be insured in the future? Retrieved from marketwatch.com.

NHTSA (2025, April). Early estimate of motor vehicle traffic fatalities in 2024 (DOT HS 813 710). Retrieved from crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov.

NHTSA (n.d.). Standing General Order on crash reporting. Retrieved from nhtsa.gov.

Reuters (2024, August 30). Life on autopilot: Self-driving cars raise liability and insurance questions and uncertainties. Retrieved from reuters.com.

Shoosmiths (2024, June 17). Automated Vehicles Act: spotlight on liability. Retrieved from shoosmiths.com.

Tesla (n.d.). Full Self-Driving (Supervised) subscriptions. Retrieved from tesla.com/support.

VICE (2025, September 9). Tesla is dropping the dream of human-free self-driving cars. Retrieved from vice.com.

Waymo & Swiss Re (2024, December 19). Comparison of liability claims for Waymo driverless operations vs. human baselines (25.3M miles). Waymo blog and technical PDF. Retrieved from waymo.com/safety and storage.googleapis.com.

Zurich Insurance (2025). Driverless vehicles and the future of motor insurance. Retrieved from zurich.co.uk.