ESG Finance in Emerging Markets: How Binding Rules Move Capital

Input

Modified

ESG moves markets only when rules are binding Subsidies, high capital costs, and weak enforcement favor fossils Make standards mandatory, de-risk finance, and train people to execute

The number that tells the story is ninety. In 2023, governments spent approximately $900 billion shielding consumers from rising energy prices, much of which was used to support the fossil fuel industry. In the same year, emerging-market green bonds totaled about $135 billion. The gap is not just a small error; it reflects the reality. Subsidies and existing assets continue to favor coal, oil, and gas, while sustainable debt in developing economies struggles to gain market share. The lesson is clear: where policy makes carbon cheap and reporting optional, the most affordable finance goes to the dirtiest fuel. Where regulations make climate risks visible and actionable, capital finds a new direction. Europe has spent a decade changing ESG from a voluntary pledge into a binding standard for investors and banks. ESG finance in emerging markets can follow this example, but only if it treats ESG as a law, supported by data, oversight, and a pipeline of profitable projects.

EU Playbook: Making ESG finance in emerging markets binding

Europe’s shift started with definitions and disclosures rather than slogans. The EU Taxonomy provides a shared understanding of what constitutes sustainable activity. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) required large companies to report climate and other ESG metrics alongside financial statements. Bank supervisors urged institutions to identify, measure, and manage ESG risks. The first companies started applying CSRD to their 2024 accounts, with reports due in 2025. Meanwhile, the European Banking Authority issued final ESG-risk guidelines in January 2025. These steps didn’t instantly green every firm. They accomplished something more fundamental: they made climate performance assessable, comparable, and costly to overlook.

The playbook continues to develop. Brussels has worked to simplify Taxonomy reporting and lessen requirements on smaller firms, acknowledging competitiveness issues. Yet the core principles remain: standard rules, consistent audits, and supervisory expectations that treat climate risk as a serious issue, rather than a marketing tactic. This approach is practical because it engages the attention of boards and credit committees, not just communications teams. When banks align their risk frameworks with climate exposures—and counterparties disclose usable data—lending behavior adjusts. Regulation acts as a steady foundation: reliable, predictable, and challenging to manipulate.

For educational systems, the EU experience conveys a crucial message. Graduates who can read a Taxonomy alignment table, create a double-materiality matrix, or convert Scope 1–3 emissions into covenant language now have market value. Business schools that incorporated this content early are already supplying talent to banks, insurers, and rating agencies. Public universities that linked procurement to the Taxonomy or Science-Based Targets are teaching through action. The key point is not that Europe has completed its transformation; rather, it is that rules, combined with skills, change how capital flows.

Why fossils still beat ESG finance in emerging markets

If renewables are now the least expensive option in many locations, why do fossil assets continue to dominate in developing countries? Part of the reason is financing. Levelized cost is not the same as levelized capital. New solar or wind projects require upfront investment, with capital costs often several points higher in emerging markets than in advanced economies. This disparity compounds over twenty years. In contrast, an existing gas or coal plant may be fully paid off, subsidized, or both. Even with current technology costs, many countries still view fossil options as a quick, “cheap” solution—until they face later costs from health issues, climate impacts, and stranded assets.

Subsidies further distort the market. During the recent energy crisis, governments invested roughly $900 billion to keep retail fuel and power affordable. Many emerging economies implemented price caps and tax breaks that made fossil energy appear overwhelmingly cheap for households and small businesses. Remove the subsidy, and new renewables, combined with storage, often offer better prices. Maintain it, and cleaner projects struggle at the bidding stage and in loan approvals. Note: the $900 billion figure is based on the International Energy Agency’s compilation of direct affordability measures as of April 2023; country data vary in coverage and timing.

There’s also a taxonomy problem. Several regional frameworks appropriately include “transition” or “amber” categories to allow for gas peakers or coal phase-out pathways. However, when criteria are vague or enforcement is weak, those categories can become loopholes—signaling progress while allowing emissions to persist. ASEAN’s Version 2 Taxonomy adopted a practical approach to coal retirement, which can be beneficial if it accelerates closures. However, its credibility relies on adequate guardrails and measurement. In short, flexible labels must be paired with strict accountability; otherwise, concessional capital will not flow in.

The investment needs far exceed current levels. Clean-energy spending in emerging and developing economies must increase several times by 2030 to stay on track to meet the 1.5–2°C climate target. The IEA estimates total global clean-energy investment at approximately $2 trillion in 2024; however, EMDEs capture only a small share and require significantly more—around $1–2 trillion annually by 2030 to align with COP28 pathways. This is not just a call for grants. It is an appeal for policies that reduce risks, blended finance at scale, and bankable projects that can attract private investment without jeopardizing public finances.

What works to scale ESG finance in emerging markets.

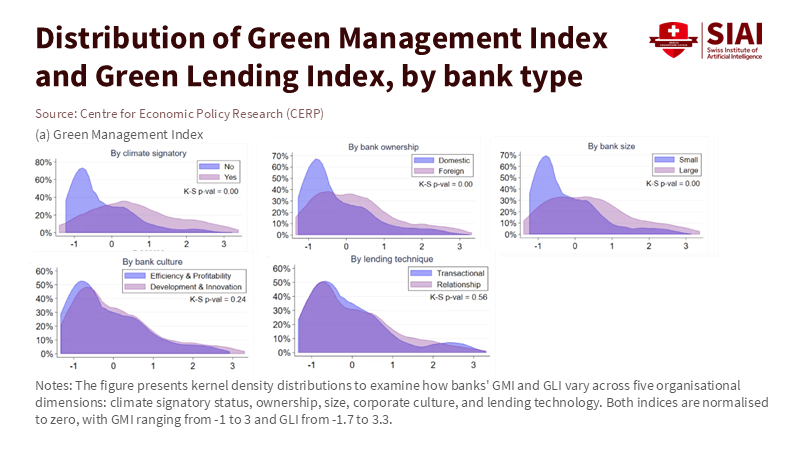

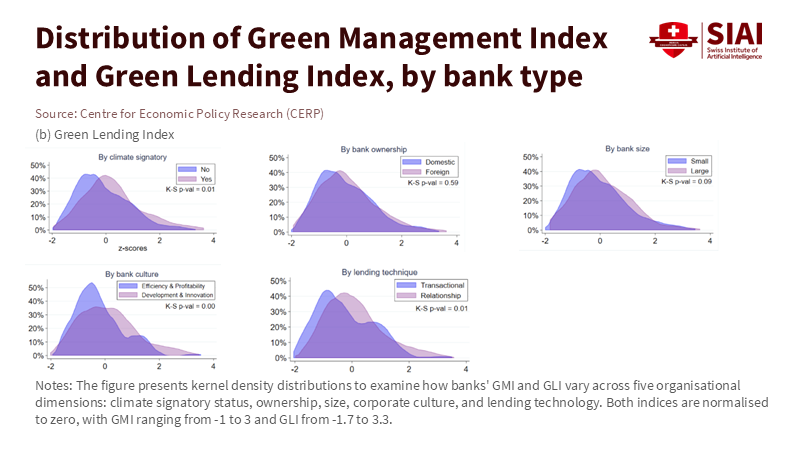

Do bank climate pledges lead to changes in lending in emerging markets? Recent surveys across many low- and middle-income countries suggest cautious optimism: signatories to international initiatives tend to have stronger green management practices and lend more to cleaner projects than their peers. However, other evidence, including syndicated loan analyses, shows that voluntary commitments alone have not significantly reallocated credit away from high-emitting sectors. The message is clear. Pledges help organize intent; rules and incentives drive portfolio changes.

Where supervisors harmonize disclosure, governance, and risk management practices, improvements occur. Brazil’s central bank is an example. Since Resolution BCB 139/2021 mandated climate-risk reporting for many institutions—building on broader social and environmental risk rules—banks must now produce structured, TCFD-style reports and integrate climate issues into governance and controls. The framework has been updated through 2024–2025, and reporting is now a key supervisory topic, rather than an optional addendum. The result is not that every borrower has changed overnight. Banks must now demonstrate their efforts, from board accountability to scenario modeling.

Capital-market depth is also necessary. The green bond market in emerging markets experienced rapid growth, reaching $135 billion in issuance in 2023. By 2024, total global sustainable debt reached over $6.9 trillion, with emerging markets—particularly Latin America—growing their share. However, issuance can decline when international interest rates rise, and many issuers still face cost premiums without guarantees or tax incentives. Note: Emerging-market issuance data is sourced from IFC-Amundi market tracking; the global cumulative figure is based on Climate Bonds’ aligned GSS+ database as of the end of 2024.

What, then, actually influences bankable demand? Three things consistently yield positive results. First, clear but strict rules: emissions-intensity thresholds tied to eligibility for credit lines or guarantees; public climate-risk reporting aligned with financial statements; and supervisory guidance that connects risk appetite to transition plans. Second, large-scale de-risking: blended financial vehicles that integrate private lenders with first-loss capital, foreign-exchange protection, and performance-based grants. The IMF’s decision to allow SDRs to support multilateral development banks’ hybrid capital is one potential leverage point; it can multiply limited public resources for more lending. Third, educational pipelines: technical assistance that helps municipal utilities and mid-sized firms transition from feasibility to bankability with standardized documents and measurable outcomes.

Latin America illustrates a key point about enforcement. Where disclosure and regulatory expectations are stringent, and where sector policies (such as renewable energy auctions or deforestation regulations) are credible, sustainable issuance increases, and banks become more supportive. Conversely, where energy prices are kept low without conditions and environmental laws are not enforced, ESG adoption falters due to narrow margins and uncertain returns. The region’s growing share of green bonds highlights what is feasible; the takeaway for others is not to emulate the label but to replicate the stringent enforcement, auction structures, and oversight that give these labels significance.

Education as the Enforcement Layer

Markets progress when people can implement the rules. This makes higher education and vocational training crucial for advancing ESG in emerging markets. The skills gap is real. Banks need credit officers who can evaluate flood risks alongside leverage ratios. Governments require analysts capable of modeling cost-of-capital scenarios for large storage projects. Cities need procurement teams who can assess a solar developer’s Taxonomy alignment before awarding a PPA. Without these skills, legal frameworks become mere paperwork, resulting in unnecessary delays and inefficiencies.

Curricula should make climate finance a fundamental subject, not an option. Accounting courses should teach double materiality and CSRD-style tagging—even in countries that do not yet report under CSRD; students will probably deal with EU clients or lenders who do. Finance programs should replace general ESG lectures with hands-on case studies using real bank data—anonymized and scrubbed—to develop green-lending policies and covenants. Law schools should offer courses on sustainable finance taxonomies and the enforceability of transition-finance claims. A semester-long “Taxonomy Lab,” partnering with ministries and banks, can do more to speed up credible ESG adoption than numerous position papers.

Universities and technical institutes can also influence incentives through their purchasing practices. When public campuses conduct open, transparent bidding for rooftop solar or bus electrification—and score bids based on life-cycle costs, Taxonomy compliance, and measurable impact—they create local examples backed by audited data. These projects then serve as templates that banks and city treasuries can replicate. The effects are significant: a procurement guide becomes a loan checklist; a student capstone project informs a municipal term sheet. This is what “binding ESG” looks like when it connects education to financial flow.

Finally, research must remain practical. We need more studies that explore which combinations of disclosure, regulatory expectations, and price signals actually alter bank credit. Emerging evidence varies on the effectiveness of voluntary commitments alone. Still, we now have sufficient data to conduct controlled comparisons and develop guidelines that a finance ministry can apply next quarter. The AFD’s recent study on the necessity of imported capital goods in developing-country transitions and the IEA’s analysis of EMDE investment gaps are excellent examples, as they address the balance-of-payments and cost-of-capital realities that ministers face daily.

We started with a gap: $900 billion in energy affordability measures, many of which are fossil subsidies, versus $135 billion in emerging-market green bonds in 2023. This gap reflects policy at work. It will not close with promises alone. It will close when nations establish ESG as an integral part of finance: standard taxonomies, required climate-risk reporting, banking oversight that views transition risk as real, and blended capital that reduces the costs of responsible actions. Education is the driving force. When classrooms teach the rules that banks must follow, and when public campuses make purchases aligned with those teachings, ESG transitions from a promise to a process. Let’s structure the next budget and syllabus to reflect that capital follows rules—because it does. Make the rules clear. Ensure they are enforceable. Train people to apply them. Then watch the financial flow change.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Agence Française de Développement (AFD). (2024). Challenges in the transition to a low-carbon economy for developing countries: Estimating capital-use matrices and imported needs. AFD

Brazilian Central Bank (BCB). (2021/2025). Resolution BCB 139/2021 and updates; Sustainability/PRSAC materials. bcb.gov.br+1

Climate Bonds Initiative. (2025). Global State of the Market (aligned GSS+ debt through 2024). Climate Bonds

European Banking Authority (EBA). (2025, Jan. 9). Final Guidelines on the management of ESG risks. Ευρωπαϊκή Αρχή Τραπεζών

European Commission. (2025). Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) overview. Finance

European Commission. (2025). EU Taxonomy for sustainable activities; delegated acts and simplification package. Finance+2Finance+2

IFC & Amundi. (2024–2025). Emerging-Market Green Bonds (market snapshots and 2023/2024 issuance). IFC+1

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2023–2025). Fossil fuel subsidies; World Energy Investment 2024; EMDE clean-energy investment pathway to 2030. IEA+2IEA+2

Lazard. (2025). Levelized Cost of Energy+ (Version 18.0). https://lazard.com

OECD/Climate Policy Initiative. (2024–2025). Global Landscape of Climate Finance.

Reuters. (2025, Apr. 3). EU Parliament votes to delay some sustainability reporting rules.

UNFCCC/WRI. (2024–2025). New collective quantified goal (NCQG) backgrounders on climate-finance targets.

VoxEU/CEPR Discussion Paper. (2025). Walking the Talk? Bank Climate Commitments and Green Lending in Emerging Markets (evidence base behind survey claims).

Wind-Down/Transition Taxonomy Context: ASEAN Taxonomy Version 2 overview (coal phase-out criteria and transitional categories).