Japan-China relations will shape Japan's classrooms more than party labels

Input

Modified

Japan–China relations now shape Japan’s classrooms and campuses Low public trust and export controls tighten research and admissions Universities should segment risk, diversify enrollment, and teach geo-literacy

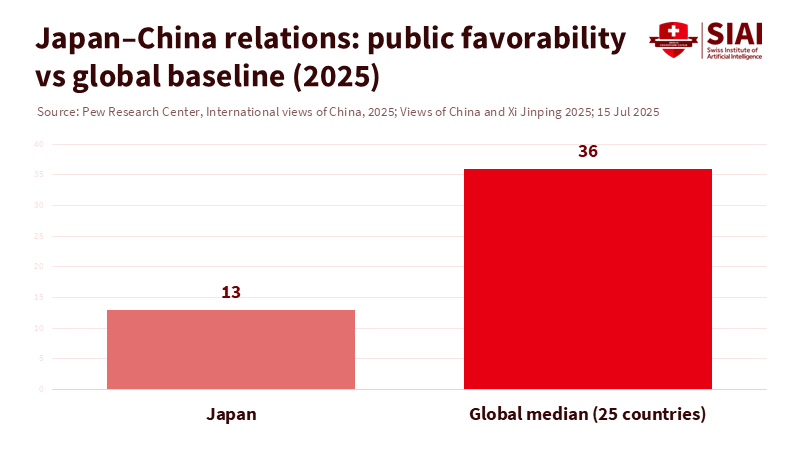

Thirteen percent. That is the share of Japanese adults who view China favorably in 2025. This figure is striking not only for its lowness but also for its role as the quiet baseline of national politics. It shapes what leaders can say and what they avoid signaling. It also influences what schools, universities, and education agencies can do. Following Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba's resignation after consecutive election losses, the Liberal Democratic Party's leadership race has reduced the space for nuance. Candidates know that any hint of leniency toward Beijing risks backlash. This is not just campaign theater. It is a structural constraint that will impact admissions policies, joint research, language courses, and student visa applications. Japan-China relations are no longer just foreign policy issues; they now drive education policy. The next prime minister will inherit a sector that needs to navigate geopolitics as carefully as trade and security.

Why Japan-China relations now define education policy

Leadership struggles are often loud but focused. This one is different. The LDP is selecting a successor to Ishiba amid deep public skepticism about China, following a tough electoral period that forced him to step down. Media reports and expert analyses highlight a field where Sanae Takaichi appeals to conservative grassroots, and younger reformer Shinjiro Koizumi enjoys strong support among lawmakers; either could lead a government that appears unaccommodating toward Beijing. For universities, this means stricter research security protocols, increased screening of collaborations, and more cautious messaging about joint institutes. The political center of gravity has shifted. Japan-China relations are now a benchmark not just in Nagatachō but also on campus.

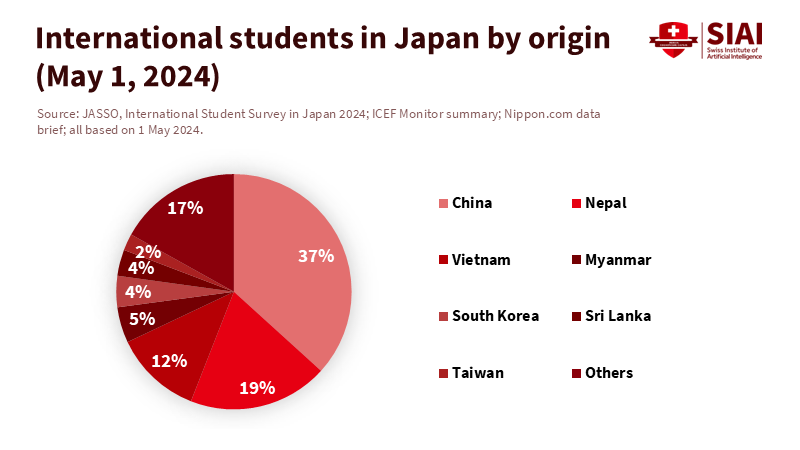

Education is also a demographic issue. The number of international students reached a record 336,708 in May 2024. Chinese students remain the largest group, accounting for approximately 40% of international students. This reliance is both an asset and a vulnerability. It enriches labs and classrooms, helps sustain regional universities, and supports graduate programs in engineering and business. It also concentrates risk if politics affects visas, funding, or the social climate. The next cabinet cannot separate Japan-China relations from enrollment planning or campus support services. A significant decline from China would hurt balance sheets and research output. Conversely, an increase could heighten public concerns about Beijing. Balancing these pressures will require more than slogans about openness with safeguards.

What does the election signal for Japan-China relations on campus?

It is tempting to view this realignment as based on party brands. It is not. Komeito, long seen as a moderating partner, has lost influence following the coalition's setbacks. Gains have come from the margins, including from the far-right Sanseito, which has hardened nationalist rhetoric and affected public sentiment. This noise limits policymakers' ability to engage pragmatically with Chinese institutions, even when academic benefits are clear. The education sector is at the forefront: it absorbs financial shocks when enrollments fluctuate and becomes the stage where national identity debates unfold. The LDP's leadership decision will be significant, but the constraint runs deeper. It is the public's lasting skepticism about China that any leader must take into consideration. Therefore, Japan-China relations will be managed through careful measures, not grand agreements.

Security laws and export control practices have already changed. Since 2023, Japan has tightened licensing requirements for numerous categories of chip equipment, with further expansions planned for 2024-2025. Universities experience this through procurement delays, compliance costs, and stricter due diligence on lab partnerships. MEXT has provided research security guidelines and is creating a culture of transparency, risk assessment, and training that U.S., European, and Australian funders now expect. This is not part of a partisan agenda. It is a steady policy direction set to continue under any LDP leader, as it aligns with public opinion and allied cooperation. For education leaders, the message is clear: create systems that expect long-term, rule-based tensions in Japan-China relations and design collaborations within those rules.

A pragmatic reset for Japan-China relations in education

The starting point is to identify risks, rather than imposing blanket bans. Universities should categorize collaborations by field, partner type, and data sensitivity. Low-risk areas—such as public health, aging policy, and classical studies—can progress using open scientific norms and mutual exchange. High-risk regions—such as advanced semiconductors, quantum sensing, and hypersonics—will require managed access, clean-team arrangements, and secure computation. This approach is not new; it aligns with MEXT's research security framework and what industry has already practiced under export controls. The new aspect is cultural: connecting compliance with academic leadership so that researchers view security as an enabler, not a limitation, to cross-border inquiry. Japan-China relations will not revert to the pre-2020 status quo. However, governance that differentiates between risk levels can maintain genuine collaboration where it is safe and valuable.

Admissions strategies must address risk concentration. Given that Chinese students are the largest group, campus leaders should set exposure thresholds by school or program and stress-test revenue under scenarios where enrollments from China fall by 10-20 percent for two years. A simple method can help. Take the latest JASSO totals and the share of Chinese students in your program. Model a 15 percent drop in that group and observe the impact on tuition-driven budgets, lab staffing, and housing. Next, prepare outreach to Vietnam, India, Indonesia, and the Philippines to cover half the gap, while investing in support for the Chinese students who do enroll to improve retention. This is not anti-China. It is basic risk management in a context where Japan-China relations are likely to remain challenging.

Visa and welfare services need adjustment for a more intense climate. Surveys and media reports indicate that communities where Chinese residents and students gather have seen incidents of online hostility. Universities should respond with visible, neutral protections: multilingual reporting systems for harassment, expedited responses in residence halls, and proactive collaboration with local authorities. This aligns with missions. It supports academic freedom and student welfare without engaging in partisan debates. It also builds social trust when Japan-China relations are tense. The policy challenge is whether leaders can de-escalate tensions on campus while national dialogue remains heated.

Curricula should incorporate "geo-literacy" without promoting moral panic. The demand for the Mandarin language is expected to remain strong. Still, programs can teach China's political economy alongside supply chain risks, export control basics, and research integrity standards. Short, skills-focused modules—like how to map a technology's dual-use path, how to interpret a sanctions schedule, and how to design data-sharing agreements—will prepare graduates for roles in trade, technology, and public service. This is where the education sector can influence policy. It can convert the challenges posed by Japan-China relations into actionable learning outcomes that enhance Japan's ability to manage a long-term strategic rivalry without cutting off knowledge.

Anticipate the critique that these efforts signify surrender to populism. They do not. They acknowledge that public sentiments are stable and cross-partisan. A mere 13 percent of favorable views of China is not just a fleeting campaign issue; it is a social reality in 2025. Leaders who disregard this will face backlash that harms students and research. A better approach is transparent risk management combined with principled openness, where the risk is low. This stance also enables Japanese institutions to collaborate with their peers in Taiwan, South Korea, and Southeast Asia on projects that minimize politically sensitive risks while maintaining robust scientific networks. Japan-China relations can form one part of a broader regional framework, rather than being the sole focus.

The final policy lever is finance. Education ministries and prefectures can use challenge grants to attract private support for joint labs in low-risk areas, with evaluations tied to open-access outcomes and industry adoption. At the same time, compliance funds should be pooled so that smaller universities can access shared services—such as export control advice, data security audits, and research security training—at a larger scale. This prevents a two-tier system in which elite institutions manage Japan-China relations effectively. At the same time, regional colleges are scaling back their international engagement. Efficiency is a strategy. It allows leaders to endorse the right collaborations and reject those that violate red lines, with documentation that withstands political scrutiny.

The number is still thirteen. It will not rise quickly. This means the next prime minister will inherit a persistent limitation: voters feel uneasy about Beijing, and competitors will scrutinize any moves that seem accommodating. Education cannot ignore this reality, nor should it. Universities and schools can view Japan-China relations as a working condition instead of an existential threat. Suppose leaders segment risks, manage enrollments, invest in research security, and update curricula. In that case, they can keep knowledge accessible where it is safe and close off areas where it is not. That is the honest path in an era when foreign policy increasingly overlaps with classrooms and laboratories. It requires discipline, not drama. The goal is a sector that avoids both naive engagement and automatic isolation, while teaching the next generation how to live, learn, and thrive amid long-term rivalry without letting it define their experiences.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Baker McKenzie. (2022, June 24). New Act on the promotion of Japan's economic security enacted.

CSIS. (2025, July 21). Japan's Upper House Election: Prolonged Instability.

East Asia Forum. (2025, Aug. 31). Ishiba's China policy increasingly contested after electoral setback.

East Asia Forum. (2025, Oct. 3). China eyes the LDP election warily.

Financial Times. (2025, Oct. 3). Japan's ruling party edges towards picking youngest leader in a century.

Hogan Lovells. (2023, Aug. 17). Japan's new chip equipment export rules take effect.

JASSO. (2025, Apr. 1). International Student Survey in Japan, 2024 (PDF).

JASSO (via ICEF Monitor). (2025, May 7). Foreign enrolment in Japan reached record levels in 2024.

MEXT. (2024, Dec. 18). MEXT's Approach for Ensuring Research Security at Universities and Research Institutions (PDF).

Nippon.com. (2024, June 28). Record Number of Foreign Students at Japanese Universities in 2023.

Pew Research Center. (2025, July 15). Views of China and Xi Jinping, 2025.

Reuters. (2025, Sept. 7). Japan PM Ishiba resigns after bruising election losses.

Reuters. (2025, Oct. 2–3). Japan's next leader may be its first woman or youngest in modern era.

Study in Japan. (2024). Result of International Student Survey in Japan (web overview).

TMTPost (EN). (2025, Jan. 31). China warns Japan over tighter export controls on chips.