Learning Economy Tariffs: How Trade Wars Hurt Education & R&D

Input

Modified

Tariffs with India, Korea, and Switzerland endanger student mobility and research in the learning economy Trade deals must lock in visa certainty, protected lab inputs, and joint research Bake education into trade to keep talent flowing and innovation alive

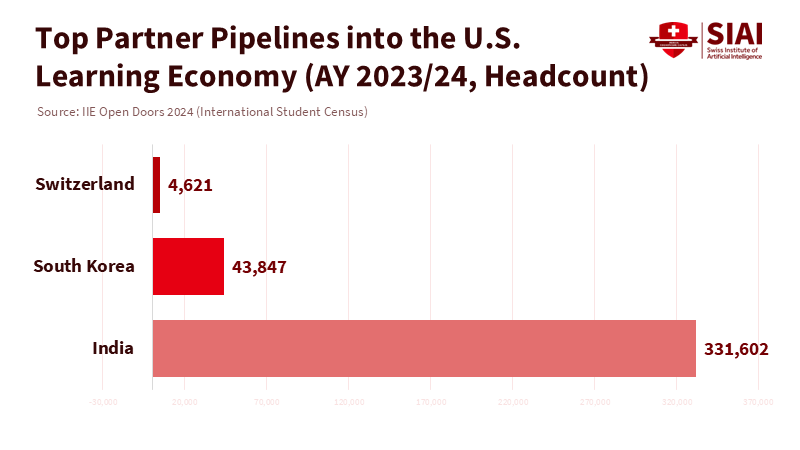

One number stands out over learning economy tariffs: 331,602. That's how many Indian students studied in the United States in 2023, the most significant number ever recorded and the biggest source of STEM talent entering American labs and classrooms. Their tuition and living expenses contributed $43.8 billion to the U.S. economy, supporting over 378,000 jobs on and around college campuses. This figure doesn't even include Korean graduate students, who excel in chip-related fields, or Swiss research partnerships in biomedicine and advanced manufacturing. This is the delicate foundation of the "learning economy": mobility, research ties, and joint commercialization that make universities vital for growth. However, in 2025, the main story revolves around punitive tariffs and brinkmanship. The United States has raised taxes at the border for dozens of partners, imposed 25% tariffs on South Korea, and, by late September, proposed 100% tariffs on branded pharmaceuticals that affect Swiss and Indian exporters. India is also struggling with U.S. taxes of "over 50%" on goods amid stalled negotiations. These are not just isolated trade battles; they are a coordinated test of the knowledge flows that are crucial for long-term productivity. If this standoff continues, the most immediate effects won't be seen at docks or factories; they will be evident in empty seats in graduate seminars, delayed clinical trials, and slower adoption of new technologies.

Learning Economy Tariffs: From Price Shocks to Talent Shocks

Traditional trade analysis focuses on tariff schedules, customs classifications, and short-term effects on prices. This overlooks the key issue in 2025: how trade shocks impact student mobility, research collaboration, and firm-level R&D, which are the actual drivers of skills development. Consider three key areas. First, U.S.–India relations. In 2024, goods and services trade totaled approximately $212 billion, with services alone accounting for over $83 billion. This growth is driven by digitally delivered IT and professional services that rely on graduate training and two-way talent flows. Disconnect the markets, and you hinder the inputs necessary for this service's growth—graduate education, OPT work experience, and research partnerships. Second, U.S.–Korea supply chains. South Korean companies produced the majority of the global DRAM and NAND in 2024–25, with Samsung and SK hynix combined supplying over half the world's memory and an increasing share of HBM, which is critical for AI. Raising tariffs to 25% or changing market access risks diverting investment and the graduate talent pipeline that supports semiconductor research and development. Additionally, the U.S.–Switzerland relationship in the life sciences is also at risk. The late-September announcement of 100% tariffs on branded pharmaceuticals—unless companies build plants in the U.S.—directly impacts Swiss firms, which employ many U.S.-trained scientists and co-fund university trials. Any disruption affects labs and clinical programs, not just trade records.

This issue is pressing because tariffs are not just a fixed tax; they create ripple effects throughout the economy. The OECD estimates that the effective U.S. tariff rate increased to about 19.5% by late summer, with growth challenges emerging into 2026. Analyses from PIIE and the Federal Reserve also show that widespread tariff scenarios slow growth both domestically and internationally, with the impacts heightened by retaliation. When you apply these broader points to higher education, a transparent cause-and-effect chain emerges: tighter margins for export-focused firms reduce sponsored research and scholarships; increased import costs for laboratory equipment slow down experiments; and uncertainty prompts some students to reconsider studying in the U.S., opting instead for Canada, the UK, or Australia. Early 2025 surveys and traffic data indicate a decline in global interest in U.S. engineering programs even before the full tariff impact is felt. In summary, tariffs act as a talent shock that travels through universities.

Learning Economy Tariffs and University Supply Chains

The world's most effective classrooms are embedded in supply chains. A Korean memory facility in Icheon connects to a machine-learning seminar in Illinois through internships, doctoral placements, and joint patents. A biopharma team from Basel co-funds a translational oncology lab at a Midwestern medical school. An AI start-up from India sponsors a faculty chair and recruits on campus through OPT. Break any link, and you slow the entire chain. This is why the 331,602 Indian students in the U.S. and the larger 1.13 million international-student community are significant in tariff policy—they are essential to U.S. advantages in AI, biotech, and clean tech. They also make higher education financially viable in numerous public institutions, where out-of-state and international tuition stabilizes budgets and supports specialized programs from quantum materials to computational linguistics.

Two recent developments heighten the stakes. First, enforcement challenges: increased OPT site inspections and visa scrutiny for STEM graduates, nearly 100,000 of whom are from India, add more uncertainty to the talent pipeline just as firms express a need for more data scientists and microelectronics engineers. Second, sector-specific tariffs: the September announcement of 100% duties on branded or patented pharmaceuticals (with exceptions for firms establishing operations in the U.S.) clashes with the structure of cross-border R&D in the life sciences, where clinical trials are conducted across various sites, and supply chains span multiple jurisdictions. Swiss firms with significant U.S. manufacturing operations may mitigate the direct tariff effects, but the policy signals still dampen new projects and complicate procurement for teaching hospitals and university labs.

We also need to acknowledge the role of Korean semiconductors and graduate education. South Korean companies supplied a large share of global memory in 2024–25 and are focusing on HBM for AI accelerators. These product cycles require talent; they depend on U.S. graduate programs for device physics, packaging, and EDA skills. Fluctuating bilateral tariffs increase the cost of collaboration at a time when Nvidia certifications, HBM4 roadmaps, and export-control compliance already strain resources. A tariff-affected environment lowers the incentive to support U.S. labs or send staff for degrees, especially if other research centers—such as those in Tokyo, Singapore, and Eindhoven—offer more favorable visa processes for the same talent.

What should schools and ministries do now?

The primary policy error is the separation of "trade" from "education." If tariffs are being used as leverage in negotiations with India, Korea, and Switzerland, education policy must be integrated into any agreement that is reached. This begins with education exemptions, which include clearly defined exemptions for university-related goods (such as lab equipment, reagents, and supercomputing components) and for student and researcher mobility (including predictable visa numbers and expedited approvals for degree-seekers in critical fields). U.S. lawmakers and agencies should view graduate-level mobility in the same light as strategic minerals: as a crucial input to national capacity. Negotiators routinely exchange tariffs for market access in sectors like autos or agriculture; they can—and should—do the same for visa guarantees, collaborative research initiatives, and mutual recognition of qualifications in health and engineering.

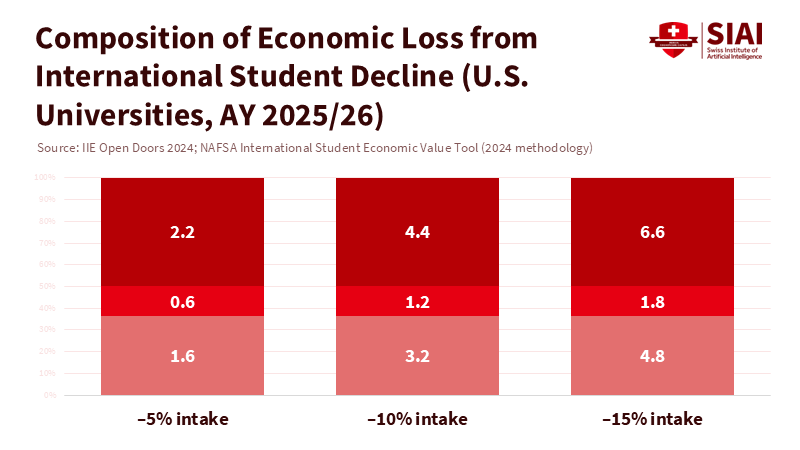

On the university front, administrators should take action now in three key areas while discussions continue. First, budget resilience: prepare for a one-year shock where international enrollment drops 10–15% and OPT approvals slow. Approve contingency plans—such as bridge scholarships, cohort delays, and program resizing—to ensure core STEM programs continue uninterrupted. NAFSA's methodology suggests that each $339,000 in export value (tuition and local spending) supports a U.S. job, making even small decreases in enrollment significant for payrolls in housing, dining, and student services. Second, create alternative pathways: broaden joint and dual-degree programs with India and Korea that don't rely on U.S. entry at the start; build in mid-program mobility so students can rotate once visa situations stabilize. Third, develop flexible research agreements: establish master contracts with Swiss and Korean firms that allow projects to be transferred between campuses or countries without requiring the redoing of paperwork every time tariff regulations change.

For India, the focus should be on safeguarding education within any early trade agreement. This means clear language assuring timely visa processing for graduate STEM students, transparent OPT rules, and exemptions for digitally delivered services that rely on U.S. graduate education, such as cloud computing, cybersecurity, and data analytics. The services channel has been where bilateral value has been growing the fastest; cutting off the graduate pipeline would harm both sides. New Delhi should also establish a reciprocal research fund—a modest pool, co-financed with U.S. partners —to protect high-impact university projects from tariff shocks and encourage firms to continue sponsoring doctoral research.

For South Korea, the priority is semiconductors and visas. The July tariff framework, which considered lowering duties from 25% to 15% in exchange for significant investments, clearly linked market access to capital commitments, giving Korean negotiators leverage to request STEM visa quotas, expedited approvals for chip-related disciplines, and a currency-swap agreement to prevent financial pressures from disrupting student plans. Universities should support this effort by establishing Korea-focused programs in microelectronics (device, packaging, EDA) with guaranteed placements at Samsung and SK hynix locations in the U.S. and Korea. If tariffs remain high, these programs will help preserve the talent loop.

For Switzerland, the immediate task is to separate ongoing clinical research and teaching hospital procurements from tariff drama. Washington's new 100% pharmaceutical tax exempts companies that are "building" manufacturing facilities in the U.S.; Swiss firms like Roche and Novartis have emphasized this point. Universities and healthcare systems should work alongside this, codifying tariff-safe supplies for trials and course materials to ensure that student rotations and fellowships tied to those firms proceed smoothly. Bern can advocate for a dedicated research corridor that recognizes co-developed molecules, trial materials, and associated data flows as protected "education-research inputs" with a specific customs code. This approach can later be extended to EU partners.

Some critics may argue that universities are overreacting, asserting that tariffs thus far have had minimal macroeconomic effects and that many companies can withstand them due to existing inventories and profits. While some indicators for 2025 show resilience and delayed impacts, education relies on application timelines, visa approvals, and lab schedules, not quarterly earnings. A student deterred this winter means a missing cohort in 2026. A delayed clinical supply order results in a lost semester for residents. Furthermore, the policy direction suggests higher effective tariff rates through 2026, and early evidence indicates a shift in prospective students looking away from the U.S. for engineering studies. Institutions cannot wait and react after the fact.

The alternative view is that this is all part of negotiation tactics; agreements will be reached because the need for security is strong. The United States requires India as a counterbalance in the Indo-Pacific and needs Korea at the forefront of semiconductor supply chains; neither side can afford a breakdown in relations. This view is likely accurate. However, the details of these agreements will affect the learning economy. Suppose deals trade tariff relief for large-scale investments without including education commitments. In that case, the outcome will be unpredictable student flows, fewer industry-funded positions, and greater administrative challenges—results that will weaken the innovation capacity those agreements are supposed to bolster. A more effective strategy is to incorporate education into the negotiations, such as reducing duties in exchange for visa stability, researching exemptions, and establishing protected laboratory supply chains. This isn't special treatment for universities; it's good industrial policy that recognizes the real bottlenecks at play.

Returning to the initial number—331,602—and the broader learning economy it represents. In a world of stricter borders and strategic competition, education is not merely a collateral issue in trade; it is the critical channel through which countries turn openness into capability. If Washington negotiates firmly with India, Korea, and Switzerland. In that case, it should maintain a long-term perspective: ensuring talent continues to flow while linking market access with friend-shoring, supply-chain stability, and budget goals. If New Delhi, Seoul, and Bern negotiate wisely, they can safeguard their students and research assets while paving the way for growth. The alternative is a loud win in tariff headlines and a quiet loss in classrooms and labs. The demand for action is apparent: include education in the agreements now—visa allocations, research exemptions, and tariff-safe learning resources—so that when everything settles, the world's learning economy emerges stronger than before.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

ABC News. "What will new furniture, pharmaceutical tariffs mean for prices?" (Sept. 26, 2025).

American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE). Engineering & Engineering Technology by the Numbers, 2024. (Oct. 27, 2024).

Associated Press. "Trump sets 25% tariffs on Japan and South Korea…" (July 7, 2025).

Business Today. "'Need to fix India': U.S. says New Delhi must open its markets…" (Sept. 28, 2025).

Congressional Research Service. U.S. Tariff Actions and U.S.–South Korea Trade (Updated Sept. 8, 2025).

Council on Foreign Relations. "Trump's New Tariff Announcements." (July 8, 2025).

DHS/IIE. Open Doors 2024 Fast Facts. (Nov. 2024).

East Asia Forum. "India faces turbulent future as US tariffs escalate." (Sept. 26, 2025).

IIE. "United States Hosts More Than 1.1 Million International Students…" (Nov. 18, 2024).

KED Global. "Korean pharmaceuticals, another victim of Trump tariffs." (Sept. 28, 2025).

KED Global. "S. Korea's Lee presses US Treasury Secretary Bessent…" (Sept. 25, 2025).

NAFSA. International Student Economic Value Tool (2024 data) and Methodology. (Nov. 2024).

OECD via Reuters. "Full impact of U.S. tariff shock yet to come…" (Sept. 23, 2025).

Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). The global economic effects of Trump's 2025 tariffs. (June 25, 2025).

Reuters. "Roche, Novartis underline U.S. plans after Trump pharma tariff announcement." (Sept. 26, 2025).

Supply Chain Dive. "US, South Korea strike tariff deal, Trump says." (July 30, 2025).

Times of India. "India says trade talks with US 'constructive', eyes early deal." (Sept. 26, 2025).

U.S. Census. Trade in Goods with India (2024); Trade in Goods with Korea, South (2024).

USTR. India — Country Page; Korea — Country Page; Switzerland — Country Page; Fact Sheet: U.S.–India Terms of Reference (Apr. 2025).

Washington Post. "Here's how much international students contribute to the U.S. economy." (May 28, 2025).

Comment