Europe's Inflation Problem Is a Budget Problem, and Schools Will Feel It

Input

Modified

Credible budgets cut inflation Rising defense and debt threaten school funding Multi-year fiscal plans can protect education

In May 2010, Greece initiated a significant one-year budget cut in the euro area, reducing its deficit by about five percentage points of GDP. This move, which included tax increases and spending cuts totaling around 11% of the country's GDP, led to a significant adverse turn in Greece's economic situation in 2013. The harsh but clear message was that when governments reduce demand and regain trust, inflation can be controlled, albeit at a significant social cost. This lesson is particularly relevant today in Europe, where welfare states are facing rising defense spending and increased debt service, even as disinflation approaches its target. The situation in France, with a 5.5% GDP deficit in 2023 and a subsequent downgrade, serves as a stark reminder that every percentage point of fiscal overshoot represents real money taken away from classrooms. Meanwhile, the euro-area HICP stands at about 2.0%, Germany is at 2.2%, and the UK remains close to 3.8%. This data underscores the re-emerging connection between fiscal issues and price trends. The historical pattern remains unchanged: indecisive budgets perpetuate inflation, while stringent budgets quell it. However, the education sector is left to deal with the repercussions in either scenario.

What history actually shows

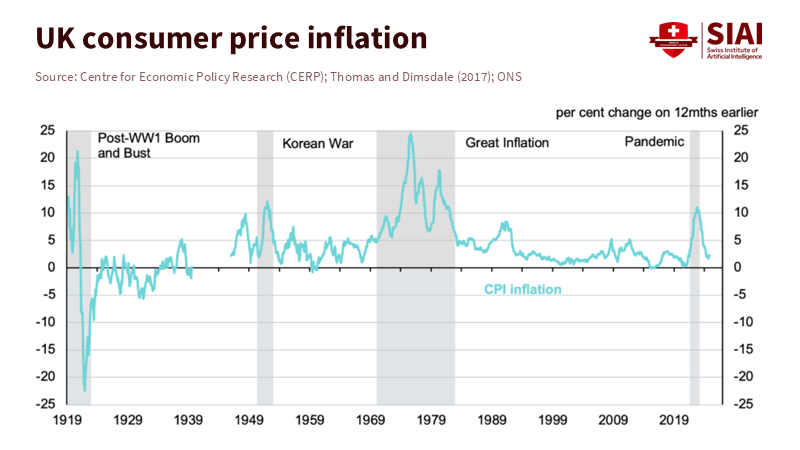

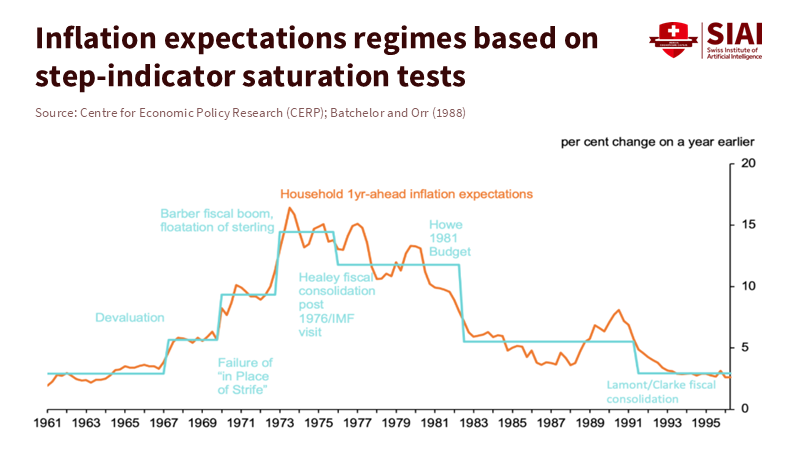

Many consider the 1970s a story of financial instability: central banks made things too easy, oil shocks occurred, and wage-price spirals emerged. All of that is true—but it's not the whole picture. The UK's Great Inflation was fueled by poor fiscal discipline and a political commitment to an overvalued pound, which weakened external confidence. In 1976, Britain sought a then-record $3.9 billion IMF loan and accepted spending cuts as part of the solution. Inflation peaked at nearly 24% in 1975, and reducing it required a strict monetary policy and a fiscal shift that demonstrated seriousness to investors and unions. This mechanism is essential for today's policy: in high-debt, welfare-heavy states, just tightening monetary policy struggles when markets doubt fiscal stability. Trust in debt dynamics and future primary balances influences how tax and spending decisions affect expectations, wage agreements, and bond yields. In simple terms, if the budget signals "no more free rides," inflation expectations shift first, prices follow later, and the real exchange rate adjusts. This was evident in Greece, where deflation led to substantial damage once the budget cuts were too steep, and it was also seen in the UK after the 1976 crisis. The idea often cited as austerity is a crude summary; the real point is more subtle: credible budget cuts are necessary (though not always sufficient) for lasting disinflation when debt is high and the welfare state is large.

Another historical correction is needed. We often claim today's inflation is different from the 1970s due to "supply shocks plus temporary factors." That was also proper back then: inflation measurements fluctuated because staples had bigger weights. The proper continuity is institutional: when policy appears "passive" regarding fiscal issues, inflation persists; when institutions collaborate to restore credibility, it declines—often faster than expected. That is why the BIS now calls for consolidation as an "absolute priority," noting that it eases inflationary pressure and reduces the need for prolonged periods of high interest rates. New research also shows that announcements about fiscal consolidation lower medium-term inflation expectations—the hidden link for wage standards and longer-term yields. Europe's new fiscal rules, adopted in April 2024, support this by requiring medium-term plans that strike a balance between investment and debt sustainability. We should see these as a form of inflation policy.

The new European arithmetic

Disinflation is real but not cost-free. The euro area's HICP is 2.0%; Germany is close to 2.2%; and France's CPI briefly dropped below 1% in the spring of 2025 as the effects of energy prices unwound. However, budget problems are worsening: deficits are larger than they were before the pandemic, and debt ratios stay high. The ECB warns that the euro-area deficit will still be approximately 3.3% of GDP by 2027, significantly higher than the 0.5% of 2019. France is at the center of this dilemma: the S&P downgrade in May 2024 highlighted a 5.5% deficit for 2023 and raised questions about medium-term budget plans. By late 2025, France's 10-year yields had matched those of Italy for the first time in years, a clear sign that markets were demanding a premium for fiscal uncertainty. For education ministries, this isn't just a macro detail. Every 50-basis-point increase in sovereign yields raises debt service costs by billions over time. Since most EU systems fund schools through public funds, these costs are deducted from payrolls, maintenance, and capital plans unless taxes are increased or other programs are reduced. Inflation that appears to be under control can resurface if policymakers fail to make tough choices.

Two additional pressures intertwine with this budget situation. First, defense spending is increasing—by 2024, eighteen NATO members are expected to reach 2% of GDP. Overall, European defense spending is growing rapidly, with Germany now approaching 2% of its GDP and planning to invest hundreds of billions of euros over the next five years. Second, social spending in large welfare states remains structurally high: France's social protection expenditures account for around 31% of GDP, the highest in the OECD and significantly above the EU-27 average of approximately 26–27%. When debt service, pensions, and defense costs are stable, "protecting schools" becomes mere rhetoric unless supported by either higher taxes or cuts elsewhere. This is where the risk of inflation returns: if governments refuse to make a decision, they may slide toward soft fiscal dominance—pressuring central banks to do less, keeping bond yields high, and allowing prices to rise through changes in expectations. The political temptation is clear; the educational cost is quieter but grows over time, as wages chase inflation, procurement contracts grow, and investments in ventilation, labs, and digital infrastructure are delayed.

What must education systems do now?

Here is the crucial shift for schools, universities, and ministries: controlling inflation is an education policy issue. In systems mainly funded by the state, defeating inflation effectively requires a budget strategy that bond markets trust and that the central bank can rely on—and it requires incorporating specific education safeguards into that strategy to avoid repeating Greece's lost decade in human capital. The path is not theoretical. Europe's updated fiscal rules require Medium-Term Fiscal Structural Plans, which should achieve three key objectives. First, emphasize credibility, not pain: announce multi-year budget cuts, specify tax-base expansion that reliably raises revenue, and establish legally binding limits on current transfers while excluding targeted education investments. Evidence shows that announcements themselves lower medium-term inflation expectations; this support for expectations can reduce future interest rates and protect school budgets. Second, focus on content: shift from broad consumption subsidies to investments in public goods that support growth—such as teacher training, early-years language and math skills, and energy-efficient campus upgrades—so that the same budget impulse doesn't merely revive demand but instead increases potential output. Third, approach indexation wisely: temporary, clear indexation of teacher pay and per-student grants to a rolling, backward-looking CPI minus a small gap can maintain purchasing power while guiding back toward 2% inflation.

A principled path to protect learning while finishing disinflation

Some argue that austerity hinders growth, and Greece's experience serves as a cautionary tale rather than a model. This is precisely why the details and timing of budget cuts are key policy tools. The Greek program was too aggressive and weakened public administration; deflation occurred, but so did a GDP collapse and a spike in youth unemployment, causing lasting damage. The correct takeaway is not "never consolidate." It is "consolidate credibly and protect human capital." The EU's 2024 fiscal framework provides room for investment as long as debt conditions improve. Countries that quickly safeguard essential education funding can credibly commit to a macroeconomic strategy while preventing the microeconomic damage that could make budget cuts politically undoable. With rising defense and debt service costs, the choices narrow to two: generate more revenue or cut broad consumption transfers. A coalition that refuses both options is a coalition that opts for higher risk premiums and stubborn inflation, which will quietly drain schools through elevated input costs and lower real budgets.

Another point is that Europe has already managed to control inflation, making the budget focus outdated. The data suggest caution. Euro-area inflation at around 2% is a victory worth defending, not something to take for granted. UK inflation, at about 3.8%, shows persistence. The ECB staff highlight that discretionary fiscal actions raised HICP by an estimated 1.5 percentage points at the peak in 2022. In other words, budgetary looseness, while understandable during an energy crisis, also extended inflation challenges. The BIS emphasizes this key point: completing the disinflationary process enables the earlier normalization of rates, reduces interest expenses, and creates a non-inflationary environment for education priorities. The longer we wait, the more we pay in both interest payments and compromise in classrooms.

Europe's education leaders should not sit on the sidelines in this discussion. They are crucial players with significant stakes. A credible four-year fiscal plan that increases taxes fairly, reduces untargeted transfers, and safeguards high-return education investments will effectively preserve real teacher salaries, prevent hiring freezes, and ensure warm labs this winter more than any temporary subsidies. It will also help keep inflation expectations steady, which is the most cost-effective support policy for schools. If politics in Paris or Berlin hesitate, the numbers won't: bond markets will penalize delays, the ECB will maintain a tighter stance longer, and governors will be asked to do more with less—resulting in learning losses and staff burnout as the hidden costs in national budgets. We have seen similar situations before. The countries that chose credibility first recovered faster and incurred lower costs.

Returning to the initial claim, all instances of inflation can be addressed. The challenge now is not knowledge but willpower. Greece demonstrated that prices can fall quickly when budget cuts are implemented, albeit at a social cost that cannot be ignored. The UK's experience in the 1970s showed that when markets doubt fiscal seriousness, tightening monetary policy only buys time until political consensus is reached. Europe is now facing a gentler problem with the same underlying logic: deficits are still considerable, defense spending is increasing, social expenditures are high, and borrowing costs are no longer trivial. The solution is straightforward. Present and implement a trustworthy fiscal plan that the ECB can rely on and that investors will reward. Protect the parts of the welfare state that foster long-term productivity—especially education—while cutting generalized transfers that stimulate demand without enhancing potential. If this is done, the final stretch of disinflation will be lasting; if not, schools will bear the costs of inflation through smaller, colder, and overcrowded classrooms. The price of trust is less than the cost of inaction. We should choose wisely.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2024). Annual Economic Report 2024, Chapter I ("Laying a robust macro-financial foundation for the future"). "For fiscal policy, consolidation is an absolute priority… relieve inflation pressure."

Bruegel (2014). "Is there a risk of deflation in the euro area?" Notes Greece's entry into deflation from March 2013.

Destatis (German Federal Statistical Office) (2025). "Inflation rate at +2.2% in August 2025."

European Central Bank (2025). HICP "Main Figures" and euro-area inflation (Aug 2025 ≈ : 2.0%).

European Defence Agency (2025). Defence Data 2024–25 (web brochure): EU defense outlays rising toward/above 2% of GDP.

European Council (2024). "Economic governance review: Council adopts reform of fiscal rules" (April 29, 2024).

European Court of Auditors (2017). The Commission's intervention in the Greek financial crisis (context: Greece's early consolidation priorities).

European Commission / ECB Data Portal (2025). Greece HICP series and euro-area HICP database.

IMF (2010). "Press Release: IMF Executive Board Approves €30 Billion Stand-By Arrangement for Greece" (front-loaded measures ≈ 11% of GDP).

IMF (2013). Greece: Ex Post Evaluation of Exceptional Access (scale and ambition of consolidation).

IMF (2024). David, A. C. Can Fiscal Consolidation Announcements Help Anchor Inflation Expectations? Working Paper 2024/060 (and 2024/03 publication).

INSEE (2025). "Consumer prices: provisional estimate May 2025" (France CPI ~0.7% y/y).

OECD (2023–2024). Social spending indicators and Society at a Glance 2024 (France, the top social spender, ~30% of GDP).

Office for National Statistics (UK) (2025). "Consumer price inflation: August 2025" (CPI 3.8% y/y).

Reuters (2025). "France and Italy's 10-year borrowing costs match for the first time" (OAT-Bund spread dynamics); Germany budget and defense shifts.

S&P Global Ratings (2024). "France Long-Term Rating Lowered to 'AA-' from 'AA'" (deficit 5.5% of GDP in 2023; downgrade rationale).

SIPRI (2025). "Unprecedented rise in global military expenditure; record number of NATO members at 2% of GDP."

VoxEU/CEPR (2022). "Past and present inflation are more similar than you think"; "Today's inflation and the Great Inflation of the 1970s: similarities and differences."

Comment